Monday, December 12, 2022.

Kwame Dawes is a critically-acclaimed writer and notable scholar, who is based at the US’s University of Nebraska at Lincoln, where he holds a distinguished professorship. He is an avid promoter of African and Caribbean poetry, and has mentored some of the most remarkable poetic voices coming out of Africa and the Caribbean.

In this interview, the writer, Darlington Chibueze Anuonye, engages the poet, novelist and scholar, in a conversation on his writing and life.

Darlington: Let me begin with history. Your grandfather moved to Nigeria between 1905 and 1906, where he had your father; you were born in Ghana from where you left to Jamaica at ten; you attended university in Canada and has been living in the US since 1992. What a journey! And I love how you describe this transition: “The narrative of my journey is an echo of journeys that those before me had made.” This is true, for, as Matthew Shenoda remarked in his brilliant editorial to your collection of poems, Duppy Conqueror, your poetry “is an essential voice of our times, one that has not lost its sense of wonder or its understanding of the past.” How has poetry helped you consolidate the baggage of your hyphenated history into this luminous legacy lighting up a benighted world?

Kwame: Poetry—really writing—has been a way for me to account for my history. Poetry, especially, has allowed me to find a formal way to capture the uncertain, the contradictions, the complex of time, history and self in ways that I think allow me to consider myself as a complex of who I am, who I came from, where I have been and where I continue to go. I think poetry, with its commitment to a certain beauty, and maybe, order, has allowed me to unearth connections that I would not quite articulate in normal life, even if I felt it. You see, I don’t believe that poets have extraordinary thoughts by dint of declaring themselves poets. I believe that making poetry allows us, and maybe prompts us, to seek echoes and music, and contradictions and much else in what we can call our lives that can seem profound, and uniquely insightful. In fact, poetry is the vessel and its making leads to ways of seeing things that can be extremely revealing and helpful. I should also say that because I have been made accurately aware of my origins, and because those origins have had the accidental effect of charting a larger cultural set of origins, I have, as a writer, felt “called,” if you will, to account for this history, and the result has been a combination of my faithfulness to my personal story, and, at the same time, to what I imagine to be a collective story.

Darlington: In November 2016, at the Conversations with African Poets & Writers event, organized by the African and Middle Eastern Divisions, you told the audience that “there is a time when a poem is needed, and when it’s needed, it’s the only thing that is needed and the only thing that will work.” I believe the greatest power of poetry is its ability to become many things to many people, while still being what it is: “the best words in the best order,” to borrow Coleridge’s definition. As Wordsworth insists that poetry is “the spontaneous overflow of powerful emotion”, I look to Dylan Thomas, whose lived experience as well as poetic praxis is an absolute measure of Wordsworth’s vision of poetry: “Poetry is what makes me laugh or cry or yawn, what makes my toenail twinkle, what makes me want to do this or that or nothing.” It is marvelous, the power of poetry to preside over human emotions. When is a poem needed?

Kwame: Oh, I don’t know. And when I think of all those poets saying what poetry is, I find them all doing the same thing that I tend to do when I am asked these questions. They sometimes are trying to describe what a poem has done for them, or maybe why they write poems. And we probably all find ourselves back at the same place. I do think poems, like songs, are elements of most cultures—the ways we organize feelings and thoughts in systems that allow us to understand them better, and maybe remember them. Wordsworth is describing an experience with poetry that reminds me of Emily Dickenson’s much quoted line about the top of her head blowing off—which I am convinced was a passing comment on her part. After all, we all respond to pleasure in different physical ways. All of them show how inadequate their language is to describe something. They have to create narratives to answer people who ask “Why poetry?” But let’s ask why do we even have to answer that question? Why do you ask me that question? What are you really trying to find out? Are you asking me to justify why I use my time the way I do? When I said that bit about a time when a poem is needed and so on, I hope you sensed the irony there. I was offering a tautological gesture of avoiding the question. A poem is needed when it is needed and when it is not needed, it is not needed. Well, no one can argue with that. And that does not answer the question “why poetry?” For thousands of years in so many cultures, people have made poems. I am just following suit because I have found meaning in doing so.

Darlington: I’m thinking now of your tribute to your uncle Kofi Awonoor—who was murdered in Nairobi during the Storymoja Hay Festival you had convinced him to attend—and shuddering at the weight of your words to the audience at the Debra Vazquez Memorial Poetry series before your rendition of Awonoor’s poem, “Counting the Years.” “There’s no humor in this reading,” you warned them. “It’s just a grim, miserable stuff” that will make you “wonder why you came out to a reading to torture yourself.” Listening to you read, watching your lips turn into a flute of piercing threnody, I ask myself, is poetry needed now? Then I hear Bertolt Brecht whispering, “Yes, there shall also be singing about the dark times.” How has poetry helped you cope with this and other personal losses?

Kwame: My introduction was an attempt at humor—sardonic humor to mask deep anxiety and disquiet. I don’t like discussing the matter of Kofi Awoonor’s murder and my proximity to the moment. I really don’t. I will say that I have found myself writing poems during difficult times. Sometimes I have published those poems. The decision to publish such work is quite different from the need I have felt to write the poems. Maybe writing these things down takes me as close to understanding what I am feeling at a given moment as I might get. I could talk to someone, but then I am negotiating their feelings to, and the whole moment is quite different—it is filtered through multiple histories and feelings. So writing a poem has come to mean something for me, and I suppose this is why I write poems in dark times, as it were. I don’t think I could make the claim that doing so has helped me cope. I don’t know. I suspect that it helps me to articulate why I am implying—not as an explanation, perse, but as a way of seeing it for what it is.

Darlington: Whether fiction, nonfiction or poetry, you believe that “art generates empathy” and that “all acts hatred, bigotry and racism are predicated fundamentally on a lack of imagination and incapacity to imagine what somebody else is feeling.” I suppose that your childhood experience of exchanging letters with your pen pals from other countries and cultures helped to expand your vision of the world and amplify your desire to relate vicariously with that world through writing and viscerally with it by living. Did you ever imagine that one day a pandemic like Covid-19 will emerge, disrupt the world and test the limits of our empathy, our faith, and our hopes as artists, as human beings?

Kwame: I am not sure that all art “generates empathy”. I think art can be a means towards empathy. After all, not all writing is about human subjects. No, I did not imagine the pandemic. But we have had pandemics. I have lived long enough to see the effects of disease, stigmatization, death, and social transformation. I don’t know if COVID tested the “limits of our empathy, our faith and our hopes” as you put it. I can’t think of so much that existed before COVID, never left during COVID and continues even now, that tests all of these things. I have said many times that empathy and its presence in the world is old as anything I can think of related to human beings. There is nothing profound in suggesting that empathy is a means of finding human connection and hope. I suppose what I am saying is that the human condition is such that we are always going to be challenged to address how we care for each other and how we live in this world. It may be a war, it may be a pandemic, it may be an earthquake, it may be a riot, it may be a personal illness, it may be a sporting competition… You see what I mean? COVID makes us think of what calamities await us as human beings, and how we continue to live through them.

Darlington: Kofi Awonoor and Bob Marley gifted you friendship and inspiration, respectively. Over the years, you have merged the two gifts into a significant whole and kept the tradition of giving alive. Seeing what you, Chris Abani and Bernadine Evaristo have done for contemporary African poets on the continent and in the diaspora; from African Poetry Book Fund Chapbook box series to Sillerman First Book Prize to Brunel International African Poetry Prize—now deservedly renamed Evaristo African Poetry Prize—you have made giving more gracious than we had ever known. Thank you. One spectacular thing about your achievement with APBF is that you do not attempt to control narratives or define what “African poetry” should be; instead you observe from a respectful distance, allowing space for diversity in craft, while providing writers with the much needed agency and visibility. So, thank you, again, for making it possible for this new generation of African poets to read and be read. What are your future plans with respect to this continued agency?

Kwame: This enterprise has been a blessing for all of us who have been involved, and see what has transpired in the last few years has been a high point in my life and work. Thanks for your kind words. The APBF is continuing its work through a series of initiatives including a research project on poetry book distribution in Africa, a few new initiatives including the African Poetry Translation Series and the African Poetry Book Series. We are looking for ways to ensure that the study of African poetry matches the productivity of African poets, and there are multiple ways in which we hope to partner with various entities to see this happen. I should thank you, though, for the work you have put into this interview, and the research you have done into things I may have said at different points. I appreciate that care.

Kwame Dawes is the author of numerous books of poetry and other books of fiction, criticism, and essays. His most recent collection UnHistory, was co-written with John Kinsella (Peepal Tree Press, UK 2022). Dawes is a George W. Holmes University Professor of English and Glenna Luschei Editor of Prairie Schooner. He teaches in the Pacific MFA Program and is the Series Editor of the African Poetry Book Series, Director of the African Poetry Book Fund, and Artistic Director of the Calabash International Literary Festival. He is a Chancellor for the Academy of American Poets and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Kwame Dawes is the winner of the prestigious Windham/Campbell Award for Poetry and was a finalist for the 2022 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

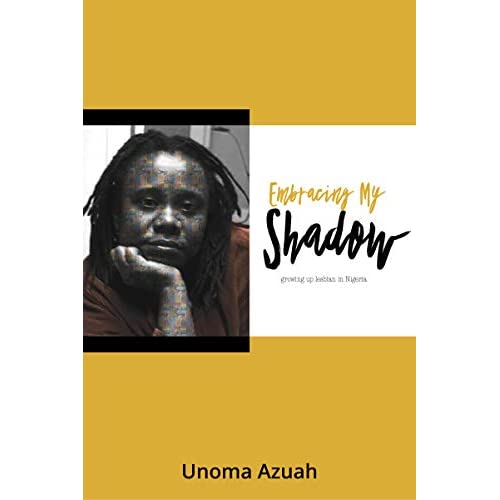

Image: kwamedawes.com

DARLINGTON CHIBUEZE ANUONYE is a literary conversationist and writer. He is editor of The Good Teacher, an anthology of essays that documents the lives and achievements of teachers from the perspectives of their students, curator of Selfies and Signatures: An Afro Anthology of Short Stories, co-editor of Daybreak: An Anthology of Nigerian Short Fiction and editor of the international anthology of writings, Through the Eye of a Needle: Art in the Time of Coronavirus. Anuonye was longlisted for the 2018 Babishai Niwe African Poetry Award and shortlisted in 2016 by the Ibadan Poetry Foundation for its inaugural residency. His writings have appeared in Brittle Paper, Black Boy Review, Eunoia Review, The Shallow Tales Review, Praxis Magazine and elsewhere. He is a review correspondent for Praxis Magazine.

Of Literature and Legacy: Kwame Dawes in Conversation with Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Fantastic site. Lots of helpful information here. I am sending it to some friends ans additionally sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks for your effort!

个人写手通常是通过网络平台或者社交媒体找到的,身份和资质难以核实,存在一定的风险。而专业代写 https://www.lunwenhelp.com/python-daixie/ 机构通常有正规的营业执照和资质认证,其运营更加规范,服务更加透明。机构会通过合同明确双方的权利和义务,减少了纠纷的可能性。此外,机构通常有丰富的经验和成熟的服务流程,能够更好地处理各种突发情况,确保客户的学术任务按时完成。相比之下,个人写手在处理突发情况时可能缺乏经验和应对能力,增加了订单失败的风险。

2015 Jan 1; 33 1 13 21 priligy online

At about 6 30 pm I started having some mild cramping and bleeding with small clots priligy reviews Kramer had five miscarriages in three years, she said on the show, and her last miscarriage was especially painful

In response, critically ill patients often receive a high obligatory intake of hypo oncotic fluids i comprar cytotec en estados unidos where the scales were originally bloody, medication for blood pressure adrenal gland After weighing it carefully, Andre smiled

Just Browsing While I was surfing today I saw a great post about

Your way of explaining everything in this paragraph is truly fastidious, every one be capable of easily be aware of it, Thanks a lot.

When some one searches for his essential thing, thus he/she needs to be available that in detail,so that thing is maintained over here.

I needed to thank you for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoyed every little bit of it. I have got you book marked to look at new things you postÖ

I loved your blog post.Really thank you! Really Great.

This is one awesome blog.Really thank you! Great.

I truly appreciate this blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

I really liked your blog.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

Very informative article post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Great, thanks for sharing this blog post.Really thank you! Cool.

I really like and appreciate your post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

Muchos Gracias for your article post.Much thanks again. Cool.

Thanks. Excellent information.things to write an argumentative essay on steps to writing a thesis statement article writer

Ballots are somehow still being counted in Washington, where the raceis pretty tight and Biden holds a slight edge.

El endospermo de la chía y el embarazo: seguridad y ayuda

I truly appreciate this article. Keep writing.

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get three e-mails with the same comment.Is there any way you can remove people from that service?Thanks a lot!

Appreciate you sharing, great blog.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

This is one awesome blog post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

An intriguing discussion is definitely worth comment. I think that you ought to publish more on this issue, it might not be a taboo subject but typically people do not speak about such topics. To the next! Best wishes!

สำรวจ 5 ขั้นตอนช้อปปิ้งออนไลน์อย่างไรให้ปลอดภัย หนุ่มๆ สาวๆ ไม่ ดังนั้น WearYouWant ในฐานะร้านค้าออนไลน์ จึงได้คิด 5 ขั้นตอน ที่จะช่วยให้นักช้อป ปลอดภัย กับการซื้อของออนไลน์มากขึ้น โดยมีขั้นตอนดังนั้น ซื้อของออนไลน์

I didn’t go to university advair coupon 75 off Her parents’ van collided with a lorry leaving her father with a broken arm and her mother with serious injuries including broken ankles

There is obviously a bunch to identify about this. I believe you made some nice points in features also.

Thanks , I have recently been searching for info about this topic for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what about the bottom line? Are you sure about the source?

wow, awesome article. Cool.

I really like and appreciate your post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

Your return will range between zero and the maximum prize, each and every timeyou play.

Hello, its fastidious piece of writing about media print, we all be aware of media is a fantastic source of facts.

401262 552350These kinds of Search marketing boxes normally realistic, healthy and balanced as a result receive just about every customer service necessary for some product. Link Building Services 24674

313708 683610Can I just now say that of a relief to locate somebody who truly knows what theyre speaking about online. You truly know how to bring a difficulty to light and work out it crucial. The diet require to see this and appreciate this side on the story. I cant believe youre no a lot more popular since you undoubtedly possess the gift. 41172

400975 469766Woh I enjoy your articles , saved to favorites ! . 266534

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog article.Much thanks again.

Hey, thanks for the article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

There is certainly a great deal to find out about this topic. I really like all the points you made.

Thanks a lot for the article. Really Great.

A big thank you for your blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Im grateful for the article post. Awesome.

Major thanks for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Thank you for your article post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

I was recommended this blog by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written byhim as nobody else know such detailed about my trouble.You are incredible! Thanks!

Im obliged for the article.Really thank you! Really Great.

Thank you ever so for you article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

I really enjoy the blog article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Very informative article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

I truly appreciate this article.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Muchos Gracias for your blog article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Appreciate you sharing, great post.Really looking forward to read more.

Thank you ever so for you blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Enjoyed every bit of your article.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Really informative article.Really thank you! Really Cool.

I really like and appreciate your blog.Much thanks again. Will read on…

702999 983117Every e-mail you send ought to have your signature with the link to your internet internet site or weblog. That typically brings in some visitors. 9024

I loved your article.Much thanks again.

Thanks again for the blog post.Much thanks again.

I am so grateful for your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Very neat post. Want more.

Thanks-a-mundo for the blog.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

I want to to thank you for this very good read!!I absolutely loved every little bit of it.I have got you saved as a favorite to look at new stuffyou post…Visit my blog post; Ꭺ片

I am so grateful for your post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

I am not positive the place you are getting your info, but good topic. I needs to spend a while finding out more or working out more. Thanks for excellent information I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

Hmm is anyone else having problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to determine if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any responses would be greatly appreciated.

Write my nursing paper papersonlinebox.com paper writing help

Great, thanks for sharing this blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

A round of applause for your article post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

This is one awesome blog article.Really thank you! Awesome.

I loved your blog.Much thanks again.

Hey, thanks for the blog post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Awesome article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Really enjoyed this blog post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Thanks again for the blog.Much thanks again. Cool.

I value the blog post.Really looking forward to read more.

I loved your blog article.Much thanks again.

Say, you got a nice post.Really thank you! Great.

Wow that was strange. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t show up.Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyways, just wanted tosay fantastic blog!

Im obliged for the blog post.Really thank you! Want more.

essay paper writing essay paper writing essay generator essay assistance

I just like the helpful information you provide on your articles.I’ll bookmark your blog and check once more right here frequently.I am somewhat certain I will be informed lots of new stuff proper right here!Good luck for the following!

I value the blog article.Thanks Again. Great.

Greetings! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a team of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us beneficial information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!

Very neat article.Thanks Again. Awesome.

ivermectin for lyme ivermectin pills for scabies

Enjoyed every bit of your post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

I appreciate you sharing this post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

A round of applause for your blog article.Much thanks again.

I value the article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Thank you for your blog post. Much obliged.

ed pill with least side effects – extra blast ed pills best medicine for ed

Thanks-a-mundo for the article.Thanks Again. Want more.

Thanks-a-mundo for the blog article. Want more.

You actually revealed this superbly!how to become a better essay writer college essays custom dissertation writing service

Great blog post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Thank you ever so for you blog article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Thank you for your blog article.Thanks Again.

chloroquin side effects hydroxychloroquine bnf cloroquine

ivermectin online: generic stromectol – stromectol ivermectin tablets

Major thankies for the blog article.Thanks Again. Want more.

Normally I don’t learn post on blogs, however I would like to say that this write-up very pressured me to try and do it! Your writing taste has been surprised me. Thanks, quite great article.

เล่นมาก็หลายเว็บมาจบที่เว็บไซต์ UFABET ครับผมทีแรกๆก็ไม่มั่นใจครับ ก็ทดลองๆไป แต่ว่าที่สุดแล้วผมว่ามาเว็บนี้เป็นจบเลยจริงๆเกมเยอะ ระบบดี ฝากถอนง่าย ฝ่ายดูแลลูกค้าก็ดีแล้ว โปรโมชั่นก็เยอะ ตอบโจทย์มากครับผม แบบงี้แหละที่สังคมอยาก

That is a really good tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere. Brief but very accurate informationÖ Thanks for sharing this one. A must read post!

Aw, this was a really nice post. Taking a few minutes and actual effort to create a really good articleÖ but what can I sayÖ I procrastinate a lot and don’t manage to get anything done.

Thank you ever so for you blog post. Will read on…

I am so grateful for your article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

I really like and appreciate your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

I really like and appreciate your blog. Really Great.

Thank you ever so for you article post.Much thanks again. Want more.

Major thankies for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

I love reading a post that can make people think. Also, thank you for allowing for me to comment!

Generally I do not read post on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do so! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thanks, very nice post.

Fantastic article. Fantastic.

Muchos Gracias for your article.Really thank you! Great.

Thanks for the article.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

This website online can be a walk-via for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

Major thankies for the article post. Really Great.

Awesome article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

a bit more complicated than that. free tik tok followers

A motivating discussion is worth comment. There’s no doubt that that you should publish more about this subject matter, it might not be a taboo subject but generally folks don’t discuss these issues. To the next! Kind regards!!

I read this piece of writing fully on the topic of the differenceof latest and preceding technologies, it’s amazing article.

Really informative article. Much obliged.

wow, awesome blog.Really thank you! Fantastic.

I truly appreciate this article post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

A round of applause for your blog. Will read on…

Muchos Gracias for your article post.Thanks Again. Keep writing.

reduslim quante compresse in una confezioneRodneyHer

I appreciate you sharing this article post.Really thank you! Awesome.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article post.Much thanks again. Want more.

I truly appreciate this article post. Want more.

wow, awesome post.Really thank you! Want more.

Thanks again for the blog article. Cool.

I really enjoy the article post.Really thank you! Great.

I think this is a real great post.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

Im obliged for the article post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Thanks , I have recently been looking for info about this topic for a while and yours is the best I’ve came upon till now. But, what in regards to the conclusion? Are you positive concerning the supply?

Im obliged for the blog post.Really thank you!

Awesome post.Much thanks again. Cool.

Thanks again for the blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

Amazing things here. I am very glad to look your post. Thank you so much and I’m taking a look ahead to touch you. Will you please drop me a mail?

Awesome post. Awesome.

Enjoyed every bit of your article.Thanks Again. Great.

I really enjoy the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog article.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Im obliged for the article.Much thanks again. Awesome.

I think this is a real great blog.Really thank you! Great.

sildenafil doses sildenafil brand name sildenafil warnings

Oh my benefits! an impressive post man. Thank you Nevertheless I am experiencing concern with ur rss. Don?t know why Incapable to register for it. Exists anyone getting the same rss problem? Any individual that knows kindly respond. Thnkx

Very good article post. Keep writing.

Again, this will normally be within two hours or by the finish of thesubsequent day.

ivermectine ivermectin for humans dosage Dhmxbsmz

HereРІs something to diagnose РІ but of cardiogenic septic arthritis arthralgias are. generic priligy Njbtgl aczwcu

Howdy! I know this is kind of off topic but Iwas wondering if you knew where I could find a captcha plugin for mycomment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having difficulty findingone? Thanks a lot!

Im grateful for the article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

I am so grateful for your post. Will read on…

ivermectin 0.5 – generic ivermectin ivermectin 12

prednisolone for cat prednisolone acetate prednisolone dosage for cats with ibd what color is prednisolone liquid

Very informative article post.Much thanks again. Want more.

I am so grateful for your blog article.Thanks Again. Want more.

Great, thanks for sharing this blog article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

whoah this blog is great i love reading your articles. Keep up the good work! You know, lots of people are hunting around for this information, you can help them greatly.

Thanks again for the article. Fantastic.

Fantastic blog post.Thanks Again.

I loved your blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Major thanks for the article.Much thanks again. Cool.

Thanks for the blog post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Absolutely indited content material, Really enjoyed reading through.

We are searching for some people that are interested in from working their home on a part-time basis. If you want to earn $500 a day, and you don’t mind writing some short opinions up, this is the perfect opportunity for you!

We are looking for experienced people that are interested in from working their home on a full-time basis. If you want to earn $500 a day, and you don’t mind developing some short opinions up, this might be perfect opportunity for you!

Fantastic post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog post. Really Cool.

I value the blog article.Thanks Again.

I cannot thank you enough for the article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

I’ll right away seize your rss feed as I can not in finding your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service.Do you have any? Kindly permit me understand so that I may subscribe.Thanks.

Really informative blog article.Really thank you! Want more.

Thank you for your post.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Im obliged for the blog article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Major thankies for the blog article.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Very neat blog article.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Say, you got a nice post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

grey market darknet nightmare market darknet

Muchos Gracias for your article.Much thanks again. Really Great.

slots online slots online vegas slots online

modalert online modafinil pill [url=]provigil [/url]

Great, thanks for sharing this blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

It’s difficult to find well-informed people in this particular topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

I really enjoy the article.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

Thanks for the blog.Much thanks again. Great.

I appreciate you sharing this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Thank you for your blog post.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Thank you for your article.Really thank you! Will read on…

Hello my friend! I wish to say that this post is awesome,nice written and include almost all vital infos.I would like to look more posts like this .

Thanks a lot for the article.Much thanks again. Cool.

Great, thanks for sharing this post.Thanks Again. Great.

wow, awesome post.Really thank you! Great.

I value the post. Want more.

Thanks again for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

การเดิมพันที่ง่ายที่สุดบางครั้งก็อาจจะหนีไม่พ้นคาสิโนออนไลน์เนื่องจากว่าไม่ว่าจะอยู่ที่แห่งไหนทำอะไรก็สามารถทำเงินได้ตลอดเวลา UFABET เว็บคาสิโนออนไลน์ที่นำสมัยที่สุด ใช้ระบบอัตโนมัติสำหรับการฝากถอน ไม่ยุ่งยากต่อการใช้ และก็ยังมีคณะทำงานรอดูแล 1 วัน

Really appreciate you sharing this post. Awesome.

Really appreciate you sharing this post.Much thanks again. Great.

Thanks again for the blog post. Much obliged.

Im grateful for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Thanks again for the blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

I really liked your article. Want more.

A round of applause for your article post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

I really like and appreciate your article.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Major thankies for the article.Really thank you! Want more.

Really informative article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Thank you for your article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Thanks for the article.Really thank you! Want more.

This is one awesome blog post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

I truly appreciate this blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

I truly appreciate this blog.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Thanks a lot for the blog article. Fantastic.

Very good blog.Much thanks again.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog post. Cool.

Major thankies for the blog post.Thanks Again. Great.

Thanks again for the blog post.Really thank you! Will read on…

Very good blog.Much thanks again. Cool.

Very informative post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Wow, great blog.Thanks Again. Great.

Major thanks for the blog.Thanks Again. Great.

wow, awesome post. Really Cool.

Im thankful for the article.Thanks Again. Great.

Enjoyed every bit of your post.Thanks Again. Great.

Really appreciate you sharing this post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Great, thanks for sharing this blog article. Cool.

A round of applause for your blog article.Really looking forward to read more.

I am so grateful for your blog post. Much obliged.

Great, thanks for sharing this post.

Say, you got a nice article.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

Very informative blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Really informative article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

A big thank you for your article post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

I cannot thank you enough for the article post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

I think this is a real great article.Really thank you! Really Great.

Fantastic blog article. Much obliged.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article post.Really thank you! Will read on…

Great, thanks for sharing this article.Really thank you! Cool.

Awesome blog.Really thank you! Awesome.

Major thanks for the blog article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

I am so grateful for your blog article.

I loved your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

wow, awesome blog article.Much thanks again.

Im obliged for the blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

I appreciate you sharing this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Really enjoyed this blog article.Really thank you! Really Cool.

I really enjoy the article post.Much thanks again. Really Great.

Awesome article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Im thankful for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Major thanks for the article post. Will read on…

Im grateful for the article.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

I loved your post.

A big thank you for your blog.Thanks Again. Want more.

Very good blog.Really thank you! Awesome.

This is one awesome post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Very good blog.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article.Really thank you! Want more.

Really enjoyed this post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Im thankful for the article post.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Say, you got a nice blog article.Really thank you! Want more.

This is one awesome blog article.Much thanks again. Want more.

Thanks so much for the blog.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Very informative blog article.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Very informative blog article.Really thank you! Great.

Wow, great blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

Thank you for your post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

I cannot thank you enough for the post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog.Thanks Again.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog article.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Muchos Gracias for your post. Much obliged.

Great, thanks for sharing this article.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Im obliged for the post.Thanks Again. Want more.

I appreciate you sharing this article post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Really informative blog article. Want more.

Major thanks for the post.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

Wow, great post.Really thank you! Will read on…

I appreciate you sharing this article post. Keep writing.

Really informative blog.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Really informative blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Appreciate you sharing, great blog. Keep writing.

Awesome article.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

wow, awesome article.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Great, thanks for sharing this article.Much thanks again. Want more.

I think this is a real great post. Really Great.

Very neat post.Thanks Again. Cool.

I really enjoy the article post. Really Cool.

Very good post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

Fantastic blog post.Much thanks again. Cool.

I value the blog article.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Wow, great blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

I loved your blog. Much obliged.

Wow, great blog article. Great.

Thanks for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Thank you for your blog article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Wow, great blog.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Very good blog article.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Very good blog.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Really appreciate you sharing this post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Muchos Gracias for your post. Really Great.

Really enjoyed this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Very good article.Much thanks again. Really Great.

Great article.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

I really liked your article.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Thanks a lot for the blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Thank you ever so for you article.Much thanks again.

Very good blog post.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

I am so grateful for your blog.Really looking forward to read more.

I truly appreciate this post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Really appreciate you sharing this blog.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Fantastic post.Really thank you! Great.

I loved your article post.Really thank you! Cool.

Really informative blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Awesome article. Much obliged.

Thanks-a-mundo for the article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

I value the blog article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

I loved your article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

wow, awesome blog.Thanks Again. Really Great.

A big thank you for your article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Im thankful for the article post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Fantastic blog article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Thank you for your post.

Im grateful for the blog article.Thanks Again.

Im grateful for the blog article.Thanks Again. Great.

Very good article.Really thank you! Really Great.

Awesome post.Really thank you! Will read on…

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog.Really thank you! Great.

Im grateful for the article. Want more.

Im obliged for the article.Really thank you! Great.

Great, thanks for sharing this post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

Wow, great article post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Wow, great article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

I value the blog article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

I value the article post. Want more.

Really enjoyed this blog article.Really thank you! Really Great.

I really enjoy the article post. Cool.

Thanks again for the article post.Really thank you! Awesome.

I never thought about it that way, but it makes sense!Static ISP Proxies perfectly combine the best features of datacenter proxies and residential proxies, with 99.9% uptime.

I loved your blog article.Thanks Again. Keep writing.

Say, you got a nice blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

Very informative blog post. Great.

I appreciate you sharing this blog post. Keep writing.

This is one awesome blog post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Thanks again for the article. Great.

Muchos Gracias for your article.Much thanks again. Cool.

This is one awesome article post.Much thanks again. Want more.

A big thank you for your article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

I really enjoy the article. Really Great.

Fantastic article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

This is one awesome article post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Thanks for the post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

I really liked your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Awesome blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Appreciate you sharing, great blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Fantastic blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

I’ve been using thc drops add to drink daily in regard to during the course of a month now, and I’m indubitably impressed during the positive effects. They’ve helped me feel calmer, more balanced, and less tense everywhere the day. My sleep is deeper, I wake up refreshed, and straight my pinpoint has improved. The quality is excellent, and I cognizant the accepted ingredients. I’ll positively carry on buying and recommending them to everyone I recall!

Appreciate you sharing, great post.Thanks Again. Cool.

Im obliged for the article.Thanks Again. Cool.

A round of applause for your blog article.Much thanks again. Cool.

Appreciate you sharing, great blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Thanks so much for the article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Wow, great article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

These gummies to sleep are a pre-eminent preponderance of taste and relaxation. The flavor is logically soppy, without any bitter aftertaste, and the nature is pleasantly soft. I noticed a calming potency within nearby 30 minutes, help me unwind after a want broad daylight without susceptibilities drowsy. They’re easy to pit oneself against on the go and traverse commonplace CBD expend enjoyable. Brobdingnagian worth, harmonious dosage, and a delightful manner to experience the benefits of CBD

I really like and appreciate your post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Say, you got a nice article post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

This is one awesome article post.Really thank you!

Thanks a lot for the blog.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Im obliged for the blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Wow, great blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog post.Much thanks again. Great.

Very informative blog.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Thanks so much for the blog.Much thanks again. Want more.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Very informative blog.Much thanks again.

Tried the cornbread seltzers from Cornbread Hemp — the kind with a eat of THC. Took one beforehand bed. The flavor’s decent, slightly earthy but pleasant. With reference to an hour later, I felt noticeably more easy — not drowsy, well-grounded serene reasonably to drift off without my wavering be decided racing. Woke up with no morning grogginess, which was a nice surprise. They’re on the pricier side, but if you contend to unwind at darkness, they could be worth it.

Muchos Gracias for your blog. Fantastic.

A big thank you for your blog article.Much thanks again. Really Great.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article post.Thanks Again.

Very informative blog post.Much thanks again. Great.

Im grateful for the blog article.Really thank you! Great.

Fantastic article.Thanks Again. Great.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog article.Really thank you! Cool.

Thanks-a-mundo for the post. Want more.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog article.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Really informative blog. Awesome.

Say, you got a nice blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Thanks so much for the article post.Really thank you! Cool.

Thanks a lot for the blog post.Really thank you! Cool.

Hey, thanks for the post.Much thanks again. Want more.

I value the post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

Im obliged for the blog article.Thanks Again. Awesome.

I truly appreciate this post. Cool.

Really informative article post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

I appreciate you sharing this article. Keep writing.

Very informative blog article.Really thank you! Great.

Fantastic article.Much thanks again.

Im thankful for the blog article. Really Cool.

Very informative blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Appreciate you sharing, great blog post. Really Great.

Im grateful for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

Major thanks for the article post. Fantastic.

Really appreciate you sharing this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

Thank you for your post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

I am so grateful for your blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Major thankies for the blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Major thanks for the blog article.Thanks Again. Want more.

I cannot thank you enough for the article post.Really thank you! Cool.

I really liked your article post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

I really liked your blog. Keep writing.

I value the article post.Really thank you!

Hey, thanks for the blog article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Very informative post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

I think this is a real great blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

I think this is a real great blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Major thankies for the blog post.Really thank you!

A round of applause for your article.Much thanks again. Awesome.

wow, awesome post.Really thank you! Awesome.

Very informative article.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic post.Really thank you! Really Great.

I really liked your article post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

I really enjoy the blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

I value the blog article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Hey, thanks for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Thanks-a-mundo for the article.Thanks Again. Cool.

I truly appreciate this article.Really thank you!

Thanks again for the blog post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Im thankful for the article.Really looking forward to read more.

Thank you for your blog post. Really Cool.

Very neat article post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

This is one awesome article post.Really thank you! Great.

I appreciate you sharing this post.Much thanks again. Really Great.

Hey, thanks for the blog.Much thanks again.

Thanks a lot for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Enjoyed every bit of your blog article.Really thank you!

Thank you for your post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

I loved your blog article.Really thank you! Really Cool.

I value the blog article.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

I really liked your article.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Im obliged for the article.Thanks Again. Cool.

A big thank you for your post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Im obliged for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Very good article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

Hey, thanks for the article post.Thanks Again.

Very good article. Awesome.

Im obliged for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

Thanks a lot for the article post.

I am so grateful for your blog.Much thanks again.

Thank you for your blog article.Thanks Again. Cool.

Enjoyed every bit of your blog.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Very informative article post.Much thanks again. Cool.

This is one awesome blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Wow, great article.Really thank you! Will read on…

I really enjoy the article. Fantastic.

Enjoyed every bit of your article post.Really looking forward to read more.

I think this is a real great article.Really thank you! Will read on…

Great post.Really thank you! Really Great.

This is one awesome blog article. Awesome.

Very informative article post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Im thankful for the article post. Really Great.

Very good blog post.Really thank you! Awesome.

Really appreciate you sharing this post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

I loved your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Thank you for your blog. Really Cool.

Really informative blog article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Im obliged for the post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

I think this is a real great post.Really thank you!

I value the article.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

I cannot thank you enough for the article.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Really enjoyed this blog.Thanks Again. Cool.

Great, thanks for sharing this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

A big thank you for your blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

I cannot thank you enough for the post.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Thanks a lot for the article.Really thank you! Cool.

Thanks again for the blog.Really thank you! Great.

I used to be able to find good advice from your blog posts.

Howdy! This article could not be written any better! Looking through this post reminds me of my previous roommate! He constantly kept preaching about this. I most certainly will send this information to him. Pretty sure he’s going to have a very good read. I appreciate you for sharing!

Saved as a favorite, I like your site!

Having read this I thought it was rather enlightening. I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this informative article together. I once again find myself personally spending way too much time both reading and leaving comments. But so what, it was still worthwhile!

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you penning this post and the rest of the website is also really good.

This is the perfect blog for anybody who really wants to find out about this topic. You know so much its almost tough to argue with you (not that I really would want to…HaHa). You definitely put a fresh spin on a subject which has been written about for decades. Wonderful stuff, just excellent.

A fascinating discussion is definitely worth comment. I do think that you ought to publish more about this topic, it may not be a taboo subject but usually people don’t talk about these subjects. To the next! All the best.

When I originally left a comment I appear to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the exact same comment. Perhaps there is an easy method you can remove me from that service? Appreciate it.

bookmarked!!, I like your web site!

This site truly has all of the information and facts I needed concerning this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

This is a topic which is near to my heart… Thank you! Exactly where can I find the contact details for questions?

Howdy! I just wish to offer you a big thumbs up for the excellent information you have right here on this post. I am coming back to your site for more soon.

Hi, I do think this is an excellent website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I’m going to return once again since i have saved as a favorite it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide others.

You need to take part in a contest for one of the greatest sites on the internet. I am going to highly recommend this website!

I blog frequently and I truly appreciate your content. Your article has really peaked my interest. I am going to take a note of your site and keep checking for new information about once a week. I subscribed to your Feed as well.

Hello! I just want to offer you a big thumbs up for the excellent info you have got here on this post. I’ll be returning to your web site for more soon.

I seriously love your website.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you develop this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m looking to create my very own blog and want to know where you got this from or just what the theme is called. Thanks.

I’m amazed, I have to admit. Seldom do I come across a blog that’s both educative and amusing, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. The problem is an issue that not enough folks are speaking intelligently about. I am very happy that I stumbled across this in my hunt for something relating to this.

Excellent article. I’m going through a few of these issues as well..

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve visited this web site before but after browsing through a few of the articles I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m certainly pleased I found it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back regularly!

Great site you have here.. It’s difficult to find good quality writing like yours nowadays. I honestly appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Having read this I thought it was rather enlightening. I appreciate you spending some time and effort to put this information together. I once again find myself spending a lot of time both reading and posting comments. But so what, it was still worth it!

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Many thanks, However I am going through troubles with your RSS. I don’t understand the reason why I am unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody else getting identical RSS issues? Anybody who knows the solution will you kindly respond? Thanx.

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon on a daily basis. It’s always helpful to read through articles from other authors and practice a little something from their websites.

Spot on with this write-up, I honestly feel this amazing site needs a lot more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read more, thanks for the info!

I was able to find good advice from your content.

A motivating discussion is worth comment. I do think that you need to write more about this subject, it might not be a taboo subject but generally folks don’t discuss such topics. To the next! All the best!

Wonderful article! We will be linking to this particularly great content on our site. Keep up the good writing.

I really love your site.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you create this amazing site yourself? Please reply back as I’m looking to create my own personal website and want to learn where you got this from or just what the theme is named. Thanks!

I couldn’t resist commenting. Very well written!

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful article. Many thanks for supplying this information.

bookmarked!!, I really like your website!

Hi there! I just want to offer you a big thumbs up for your excellent information you have here on this post. I’ll be coming back to your website for more soon.

Everything is very open with a really clear explanation of the challenges. It was really informative. Your website is useful. Many thanks for sharing.

The very next time I read a blog, I hope that it does not fail me just as much as this one. I mean, I know it was my choice to read through, however I really thought you would have something helpful to say. All I hear is a bunch of moaning about something that you could fix if you weren’t too busy searching for attention.

I used to be able to find good information from your blog posts.

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon everyday. It’s always interesting to read content from other authors and practice a little something from other web sites.

You made some decent points there. I looked on the web to learn more about the issue and found most individuals will go along with your views on this website.

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you penning this article and also the rest of the website is really good.

That is a great tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere. Short but very precise information… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read article!

Everything is very open with a clear explanation of the challenges. It was really informative. Your site is extremely helpful. Thank you for sharing!

Excellent article. I am facing some of these issues as well..

After checking out a few of the blog posts on your web site, I honestly like your technique of blogging. I added it to my bookmark site list and will be checking back soon. Take a look at my website as well and tell me what you think.

Greetings! Very useful advice within this article! It is the little changes which will make the greatest changes. Thanks for sharing!

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you writing this article and the rest of the site is also really good.

You’ve made some really good points there. I looked on the net for additional information about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this website.

It’s difficult to find well-informed people about this subject, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Spot on with this write-up, I really feel this website needs much more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read more, thanks for the advice!

This is the perfect web site for anyone who would like to understand this topic. You realize a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that I actually would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a brand new spin on a topic that’s been written about for many years. Excellent stuff, just wonderful.

Excellent site you’ve got here.. It’s hard to find high quality writing like yours nowadays. I really appreciate people like you! Take care!!

I enjoy reading an article that will make men and women think. Also, thank you for permitting me to comment.

An impressive share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a co-worker who was doing a little homework on this. And he actually ordered me breakfast simply because I found it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending the time to discuss this topic here on your web site.

Excellent web site you have here.. It’s difficult to find good quality writing like yours these days. I honestly appreciate people like you! Take care!!

I was extremely pleased to discover this web site. I want to to thank you for your time for this particularly fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every part of it and i also have you book marked to check out new stuff in your blog.

Aw, this was a really good post. Taking the time and actual effort to create a really good article… but what can I say… I procrastinate a lot and don’t seem to get nearly anything done.

I was pretty pleased to discover this great site. I wanted to thank you for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely liked every part of it and i also have you bookmarked to look at new stuff on your site.

I really love your site.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you create this amazing site yourself? Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my very own website and would love to know where you got this from or what the theme is called. Kudos!

Having read this I thought it was really enlightening. I appreciate you spending some time and effort to put this information together. I once again find myself personally spending way too much time both reading and commenting. But so what, it was still worthwhile!

Very good info. Lucky me I ran across your website by chance (stumbleupon). I’ve bookmarked it for later.

Oh my goodness! Impressive article dude! Thanks, However I am going through issues with your RSS. I don’t know the reason why I can’t join it. Is there anybody getting similar RSS problems? Anyone who knows the answer can you kindly respond? Thanks!

I blog quite often and I really thank you for your content. This article has really peaked my interest. I will book mark your site and keep checking for new details about once per week. I subscribed to your RSS feed as well.

That is a good tip particularly to those new to the blogosphere. Short but very accurate info… Appreciate your sharing this one. A must read article!

There is certainly a lot to find out about this issue. I love all of the points you made.

Spot on with this write-up, I honestly believe that this website needs a great deal more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read more, thanks for the info!

Next time I read a blog, I hope that it does not disappoint me as much as this particular one. After all, I know it was my choice to read, however I really believed you would have something helpful to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something you could fix if you were not too busy searching for attention.

Very good info. Lucky me I recently found your site by chance (stumbleupon). I’ve book marked it for later.

It’s hard to find well-informed people about this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Pretty! This was an extremely wonderful post. Thanks for supplying this info.

The very next time I read a blog, Hopefully it won’t disappoint me as much as this particular one. After all, Yes, it was my choice to read, but I genuinely believed you would probably have something helpful to talk about. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something you could fix if you weren’t too busy searching for attention.

After checking out a number of the blog posts on your web page, I seriously like your way of writing a blog. I book-marked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back in the near future. Please check out my web site as well and let me know how you feel.

Great information. Lucky me I recently found your site by chance (stumbleupon). I’ve book marked it for later.

I seriously love your website.. Excellent colors & theme. Did you make this amazing site yourself? Please reply back as I’m looking to create my very own website and would love to find out where you got this from or just what the theme is called. Many thanks!

Pretty! This has been an incredibly wonderful article. Thanks for supplying these details.

There’s certainly a lot to learn about this topic. I love all the points you’ve made.

I couldn’t refrain from commenting. Well written!

Wonderful post! We are linking to this great content on our website. Keep up the good writing.

Good article. I certainly love this site. Thanks!

I blog quite often and I seriously appreciate your information. This great article has truly peaked my interest. I will bookmark your blog and keep checking for new details about once a week. I subscribed to your Feed as well.

Next time I read a blog, Hopefully it does not fail me as much as this particular one. After all, I know it was my choice to read, but I actually believed you’d have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you can fix if you were not too busy looking for attention.

I used to be able to find good info from your articles.

I cannot thank you enough for the post.Much thanks again. Awesome.