On Herbie Hancock’s “Spider”

Monday, June 11, 2007.

By Kalamu ya Salaam of Kalamu.com

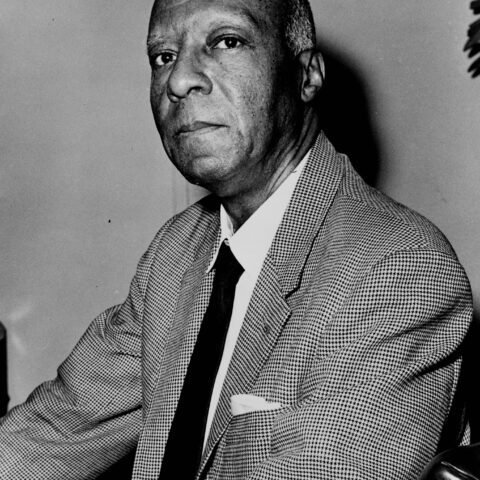

Herbie Hancock is one of the most popular jazz musicians ever, albeit his popularity is based in large part not on his jazz but on his diverse forays into pop music. This brief overview focuses on his early jazz periods as both a performer and composer.

Born April 12, 1940 in Chicago, Herbert Jeffery Hancock was a child prodigy who started studying piano at age five and played Mozart concerts at age eleven. By the early sixties he was working regularly and was well respected as a jazz pianist. His first album, Takin’ Off (1961) produced the now-classic composition “Watermelon Man,” which went on to be a staple of jazz, fusion and funk bands.

In May of 1963, Miles Davis requested Hancock join a new band Miles was putting together. That group eventually included Ron Carter on bass, Tony Williams on drums and Wayne Shorter on saxophone along with Hancock and the leader, Miles Davis. The ensemble was critically acclaimed as Miles Davis’ second great quintet. It was in this context that Hancock developed an influential approach to jazz piano, an approach that featured advanced harmonics, often borrowing techniques from classical music, as well as an open and sometimes esoteric rhythm approach that gave a floating feel to the group’s swing.

During Hancock’s tenure in the piano chair with Miles, Herbie was also concentrating on composing, but rather than record most of his compositions with Miles, Herbie offered the fruits of his labor under his own name, producing numerous popular recordings. The highpoint of them was undoubtedly Maiden Voyage (1965), which was essentially the Miles Davis band with Freddie Hubbard replacing Miles.

The composition “Maiden Voyage” is now a jazz standard. When Miles became interested in incorporating rock with jazz to produce his version of fusion, Herbie Hancock was more interested in electronics. By then Herbie had established himself not only as Miles’ pianist but as a composer and bandleader who had produced his own popular and widely-respected albums. If Hancock’s tenure with Miles was the great post-bop period, Herbie’s interest in electronic music has sometimes been dubbed his Mwandishi period because during this time Hancock used the Swahili name.

The Mwandishi period produced three legendary albums, two on Warner Brothers: Mwandishi (1971) and Crossings (1972) and one album on Columbia: Sextant (1973). The Mwandishi group consisted of Jabali Billy Hart on drums, Mchezaji Buster Williams on bass, Mwile Bennie Maupin on reeds, Mganga Eddie Henderson on trumpet, Pepo Julian Priester on trombone, plus Dr. Patrick Gleeson programming and performing on synthesizer. Herbie Hancock was now playing electronic keyboards as well as acoustic piano. (Gleeson is not present on the VSOP recording.)

After switching to Columbia Records, Herbie Hancock made a decision to go in a different direction with his music. In the liner notes to a Warner Brothers compilation that spotlighted the Mwandishi recordings, Hancock said he was seeking a more popular and less experimental orientation for his music. The Mwandishi recordings, although full of rhythm, were not perceived as popular dance music. Hancock’s next period, known as the Head-hunters period, would be funk oriented.

Hancock and the Rockit band (Pic: www.herbiehancock.com)

It would be an over simplification to say that Mwandishi’s work was suffuse with African rhythms on the bottom and Sun Ra-like electronic experimentation on the top, especially because in some ways that generalization is also true of the Head-hunters music. It is accurate to note however that the avant garde tendencies and abstract experimentation were replaced with funk driven, catchy melodies as the foundation for the jazz improvisations.

It is important to understand that The Head-hunters were still primarily a jazz band. All of that would change radically when Hancock went into his next creative phase, sometimes called the Future Shock era. Even though Herbie became associated with electronic dance music and had his largest hit with the song “Rockit,” Hancock continue to record acoustic jazz with his VSOP group.

In 1976 George Wein presented Hancock in a retrospective concert as part of the New York Jazz Festival. The currently out of print, two-LP (now a double CD) recording VSOP was a success both musically and as a retrospective. On one recording you hear each of the three bands playing at full throttle making it easy to compare and contrast the three divergent although not unrelated styles.

I don’t have a favorite. I like all three eras. I do think that the Head-hunters band on this live recording is the best of the Head-hunters and for that reason, we’re featuring one of the two cuts from them that are included on the VSOP album. This Head-hunters line-up was Paul Jackson on electric bass, James Levi on drums, Bennie Maupin on reeds, Kenneth Nash on percussion, Ray Parker Jr. and Wah Wah Watson on guitar, led by Herbie Hancock on keyboards.

It is highly instructive to compare the three drummers and the ways in which Hancock employs rhythms. Feel the power poly-rhythms of Tony Williams, who also uses space as a rhythm. Observe the adroit aural paintings of Billy Hart, who uses his drum kit as a canvas almost as if he had been influenced by French Impressionists on the soft side and West African mask makers (who were the seminal influence on French Cubists) on the angular side of rhythm making.

Rock back and forth with the bifurcated jazz and funk drumming of James Levi whose right hand plays the ride cymbals with a jazz feel while his left hand provides a heavy back beat on the snare and his feet on the sock cymbal and bass drum bridge the two styles of drumming. It’s all marvellous.

Whether swinging acoustically with VSOP, exploring space with Mwandishi, or funking it up with the Head-hunters, for all his experimentation Hancock never ever drops the beat. Numerous critics have commented on Hancock’s classical background and his advanced use of harmony but I believe the most distinctive element of Hancock’s music is his understanding and use of rhythm.

I don’t know but I hope that the actual concert was longer than what has thus far been released and that at some future date the entire concert will be released. On the evidence of the VSOP recording, it was an inspired concert that featured passionate performances from three different bands at the top of their respective, different and distinctive game.

Kalamu ya Salaam is a New Orleans-based writer and filmmaker. He is also the founder of Nommo Literary Society – a Black writers workshop.

Please e-mail comments to comments@thenewblackmagazine.com

I think this is a real great blog article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

These are in fact wonderful ideas in concerning blogging.You have touched some good things here. Any way keep up wrinting.

Really informative blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

Really appreciate you sharing this blog.Thanks Again.

I really enjoy the article.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

I think this is a real great blog. Great.