By Wilfredo Gomez | With thanks to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Tuesday, September 30, 2104.

A true artist is willing to die for what they believe in, ideologies, principles, behaviors and actions that are indicative of a way of life, a paradigm changer in search of something honest, pure, in essence, something larger then themselves. Would the artist feel the same, if we gradually took away the use of some body parts, a kind of social experiment that seeks to approximate living with disability?

In seeking to make a message intelligible to his core audience, Kanye West recently mentioned rap music, real music, real expression, and real artistry during the most recent leg of his Yeezus tour in Australia. But as I listened to Kanye West’s recent demand that audience members rise to their feet, less the show would be paused, I was left to ponder a set of questions: is rap music an appropriate creative outlet for the disabled body?

Is real expression a conceptualization of material realities that takes into equal account the disabled and disabled body? How might the iterations of that manifestation change when thinking about the visible and invisible disabilities that represent the prospects and possibilities of being, presence, and performance? What does it mean to perform hip-hop as an able or disabled body? Does the artist’s search for the real lie at the intersections where the reception of the aural cues birthed from creative genius meet the kinesthetic demands of getting on up and getting on down?

While Kanye West’s recent incident makes headlines, we must not forget that just several years ago, rapper Busta Rhymes found himself in a similar situation at a concert, having called out an audience member who was wheelchair bound, and as a result could nor (or perhaps would not) elicit the kind of energy and response requested of the artist. I am reminded that while larger venues and mainstream artists command the attention of space and seats, a good number of concert venues are places where standing only rules apply. That being said, one can highlight the American with Disabilities Act and its legal and political realities that call for the appropriate accommodations of equal access and accessibility, but what does it mean to critically examine and inquire into having access to the disabled or alternately-abled body at a performance venue.

Kanye’s pause and line of inquiry into the energy of the room, or lackthereof, elicits responses that range from laughter to flat out boos. Furthermore, we as listeners are privy to the thoughts of audience members as we hear the comments, “how dare you disobey him” alongside everyone chanting in unison “stand up!” What is perhaps most troubling during this exchange, or lacktherof, is Kanye’s blatant disregard for difference. A crowd stands, leaving two audience members seated, while Kanye suggests that they either stand or be removed.

This all-or-nothing response on the part of Kanye West the artist, leaves several things to be highlighted, one of which is the fundamental failure to conceive of difference within the oftentimes myopic lens of the world of hip-hop, particularly rap music. One can contrast this ultimatum posed by Kanye, thinking about how he as an artist situates himself vis-à-vis the punditry and stigma surrounding rappers and the media’s (mis)reading of their difference(s). Kanye shines a light on his “difference” as a rapper, while simultaneously stripping these two audience members of their agency, autonomy, and ownership over their respective bodies.

Another poignant matter highlights the fetishized nature of the alternately-abled body and its presence as both commodity and consumer, readily available to be disposed of, but surely capable of having access to the kinds of financial capital necessary to even secure a seat and be present at any artists live show.

Its rather poignant and perhaps a little too coincidental that the song disrupted by the presence of disabled bodies present at Kanye’s live show was “Good Life.” At an elementary level, Kanye’s call for a standing audience equates the act itself (standing) with a good time being had. The inability to stand is a direct affront to the standards and norms of a hype show in the realm of hip-hop culture. This presumes the existence of an unwritten, yet acknowledged script that seeks to qualitatively measure the essence of a great live performance. However, in doing so, there are dominant narratives that circulate that have literal and symbolic consequences for the kinds of violence and ridicule we project onto disabled bodies.

Do we honestly expect disabled hip-hop heads to be apologetic for being disabled? If so, are there unintended consequences for the kinds of pushback and criticism we hold artists accountable to?

Disabled bodies are made invisible by our collective efforts to make them legible. Kanye West may have opted to continue his live show when a bodyguard confirmed the credibility of the disabled body, but his foray into the song “good life” chipped away at his artistry and the quest for something real by transforming music into what fellow rapper Elzhi called “mu-sick!”

***

Wilfredo Gomez is an independent researcher and scholar who can reached via Twitter at @BazookaGomez84 or via email at gomez.wilfredo@gmail.com

Turn Down for What?: Hip-Hop and the Misgivings of Disability

Thank you for your article.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

A fascinating discussion is definitely worth comment. I do believe that you should write more on this subject matter, it might not be a taboo matter but typically people don’t talk about these subjects. To the next! Kind regards!!

tadalafil/sildenafil combo tadalafil pulmonary arterial hypertension

It’s an awesome post designed for all the online visitors; they will get benefit from it I am sure.

Thank you ever so for you blog article. Much obliged.

Really informative blog post.Really thank you! Great.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Very informative blog article.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Very neat blog post.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

generic lyrica 2018 – lyrica medicine generic vipps canadian pharmacy

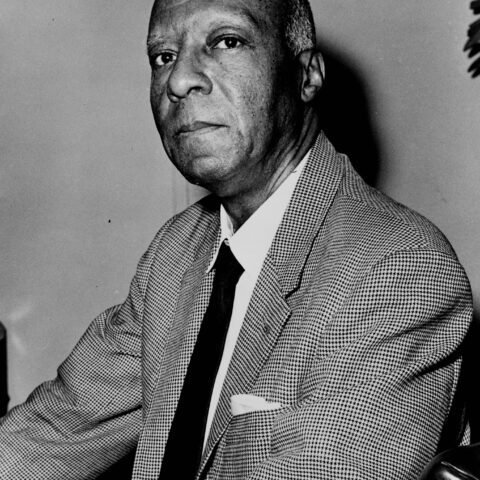

Very interesting points you have observed , regards for posting . “The best time to do a thing is when it can be done.” by William Pickens.

losartan potassium/hydrochlorothiazide does hydrochlorothiazide cause weight gain

Very great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wanted tosay that I have truly loved browsing your blog posts. Afterall I will be subscribing in your rss feed and I’m hoping youwrite once more very soon!

Hi there, after reading this remarkable post i am alsocheerful to share my knowledge here with mates.

ivermectin dosage cats injectable ivermectin for goats

Aw, this was an exceptionally nice post. Taking the time and actual effort to make a great articleÖ but what can I sayÖ I put things off a lot and never manage to get nearly anything done.

I need to to thank you for this wonderful read!! I certainly loved every little bit of it. I’ve got you book-marked to look at new stuff you postÖ