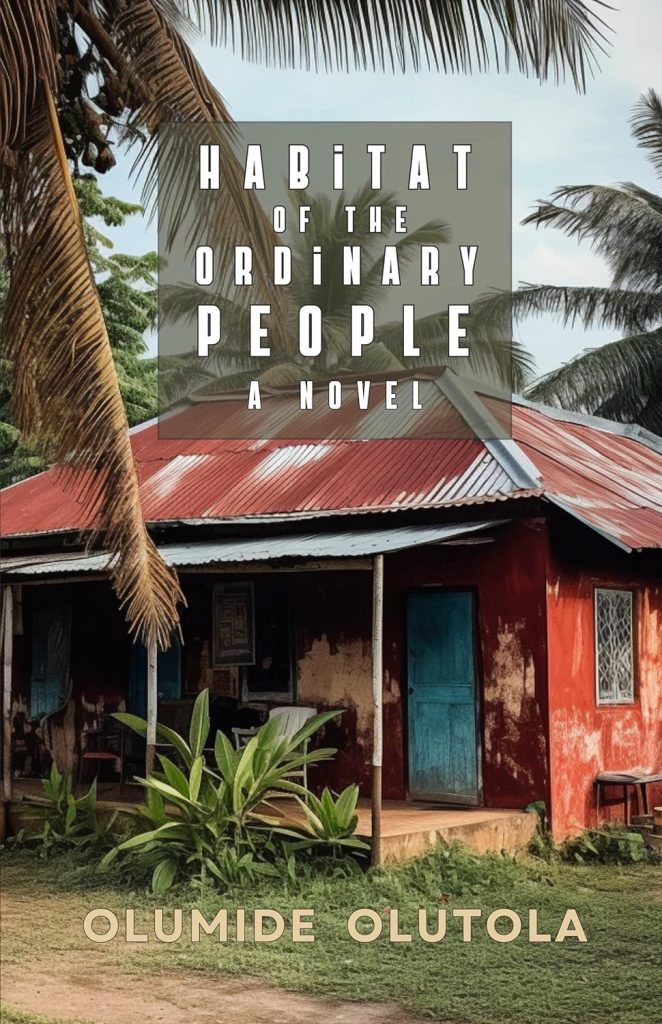

A Short Story by Bunmi Fatoye-Matory

Friday, June 28, 2024.

Somewhere in Rọ́lákẹ́’s childhood, she learned about Mercedes Benz, but not in a book, neither by sight nor on television. Television had yet to arrive in her town when she was a child. She learned about Mercedes Benz at the same time she was becoming aware of the world, and of her father’s rage. In their town and all the surrounding towns, in 1960’s Nigeria, no one drove such a car. No one could afford to. The few people who owned cars in that area drove Peugeot 403, called Pijó and the ubiquitous Volkswagen, affectionately called sọ-kí-nsọ̀ or ìjàpá. The only man who drove an exotic car, called Citron, was a lawyer who lived in Ìbàdàn and passed through their town every month while going to see his family in the area. The road to the big cities passed through Rọ́lákẹ́’s town. Many of the children, through their underground message system, knew the time of the month he would be passing and gathered to wave at him. He smiled and waved back. Rọ́lákẹ́ took part in this ritual twice and stopped. She thought the slightly green Citron was not pretty, although the boys talked excitedly about it. Rọ́lákẹ́ would only learn later from her city-raised friends at university that Citroen was an expensive French car. In fact, one of her roommates in the second year said her father, a judge, drove it. As for Mercedes Benz, she never saw one in the years she attended primary and boarding secondary schools in her area. Not even the parents who visited their children during the monthly visiting days drove such a car. Her father, like most teachers, drove Volkswagen, which everyone sọ̀-kí- nsọ̀. His car was cream-colored. His teacher’s modest salary might be high in their agrarian region, they were not high enough for city-type luxury consumption. She and her siblings had always been proud of her father’s Volkswagen until one classmate derisively said “Sọ̀-kí- nsọ̀ ni Bàbá ẹ ńgùn,” after seeing her with her parents on one visiting day. Rọ́lákẹ́ later learned this classmate’s father didn’t even have a car, but Rọ́lákẹ́ for the first time became self-conscious about her father’s car.

But her father’s dream of success was a Mercedes Benz. He said this many times while whipping her and her siblings for one infraction or the other, or insulting their mother for any number of reasons. “I would be driving a Mercedes Benz now but for you,” he raged. He blamed the children and their mother for this setback. His financial responsibilities to them were a constant source of anger. Yet, he stopped their mother, a teacher, from working. He complained bitterly about paying school fees, feeding them, buying clothes, shoes, food, and other necessities. But for all these, he would have been rich enough to buy a Mercedes Benz, he reasoned. Rọ́lákẹ́ was always curious about what this mysterious car looked like. Other children who probably had never seen it either talked about it with reverence, and called it Mẹ̀sí Olóyè. It was the king of all cars.

Rọ́lákẹ́ did not ride in a Mercedes Benz until her third year at the University of Ifẹ̀. She had seen a few driving past, usually with a man or woman sitting at the right corner in the back, the owner’s corner. It always brought back memories of an angry father raining curses on them and beating them, her father’s face twisted with anger, saying hurtful things to her mother, implacable. Rọ́lákẹ́ had gone to Sábó Market in town to buy some condiments for some stew and jollof rice she wanted to make for her birthday. She had already invited her friends. It would be her first time making jollof rice. She finished shopping and stood by the roadside to wait for a bus going to the gate of her campus. She had enough money for a taxi, but she would rather take a bus to save some money. Women spread their wares close to the road and she enjoyed the humming and buzzing of the market. She was watching the bargaining between two women across the road when a yellow Mercedes Benz pulled up next to her. It was spotless as if it had just been washed and polished. A man in a maroon guinea brocade agbádá and blue f̀ilà asked where she was going, and if she wanted a ride. She told him she was going to the campus and yes, she wanted a ride.

“Ha, you are a student at Ifẹ̀. Mo mọ̀ bí mo ṣe rí ẹ.”

“How did you know?” she asked.

“Because Ifẹ̀ girls look different. They look different from town girls.” Rọ́lákẹ́ was puzzled. She thought of herself as modest with simple dresses and low cut hair. She was a budding feminist. Her membership in the male-dominatẹd paramilitary Man’O-War Club and the Marxist revolution-breathing Alliance For Progressive Students (ALPS) attested to her political and personal goals. She didn’t perm her hair, polish her nails and or wear lipstick. Those were trivial pursuits. As for Man’ O War, she joined to keep fit and to prove that what boys can do, girls can do as well. She had often heard that male students teased each other when town girlfriends visited. They howled and shouted “bushmeat” as the poor girls walked along the corridors of Fájúyì or Awólówọ̀ Hall, letting them know they were considered unsophisticated, unlike university girls.

“Come in,” said the man.” “My name is Báyọ́. Kílo rúkọ ẹ?”

“Rọ́lákẹ́,” she replied. Rọ́lákẹ́ noticed the car was just as spotless inside. The seats were made of fine leather which was the smell inside the car. The man’s skin was smooth and his nails were clean. He rolled up the window and turned on the air conditioner. Rọ́lákẹ́ stole a look at the back and saw a leather briefcase and many files.

“What are you doing in the market?” the man asked

“It’s my birthday tomorrow and I came to buy condiments to make some food for my friends.”

“Am I invited?” the man teased. Rọ́lákẹ́ only smiled. She was going to turn twenty in a few days. This was not the first time she would be given a ride by a strange man. She was used to their small talk and flirtations, but they always dropped her off at her destinations once she let them know she was not interested in the bed part of it. Rọ́lákẹ́ had been taken interest in men lately. They were different from the men in her pre-university days who were feared and revered like her father and her teachers. As a university student, she found that she had lost that fear, but she still revered her lecturers. She also discovered men now treated her mostly with curiosity and respect.

Báyò expertly shifted from one gear to another and told Rọ́lákẹ́ he was the head of a bank in the area, that he had been transferred from Lagos, and had only been in Ifẹ̀ for a few months. His wife and children lived in Lagos. He was transferred so often he and his wife decided she should stay with the children in Lagos. He lived in a guest house owned by the bank.

“What are you studying?” he asked

“Biology.”

“Ah, our young scientist. I studied economics at U.I. and went to work with the bank after. Rọ́lákẹ́ didn’t say anything but smiled, that smug smile that said Ifẹ̀ was a superior university. He smiled too, and as if reading her mind said “Ibadan is better than Ifẹ̀.” She looked at him and laughed. He kept smiling and said he could tell what she was thinking because he had two younger siblings studying at Ifẹ̀ and he never stopped hearing about how great Ifẹ̀ was, greater than Ibadan. He asked if Rọ́lákẹ́ was hungry and she said yes. He asked if she would like to come with him to the restaurant where he was going to have his lunch. She did not mind.

He drove to a restaurant called Food Is A Good Friend To The Skin. On the menu booklet was a picture of a couple looking robust and well fed, dressed in lace materials and jewelry. Rọ́lákẹ́ said it would have been better if they didn’t translate the Yorùbá saying into English ‘Ońjẹ Lọ̀rẹ́ Àwọ̀.’ “More poetic,” she said. He smiled and said, “I thought you are studying Biology and not Linguistics.” Rọ́lákẹ́ said she wanted to study English but Biology was a compromise with her father who wanted her to study medicine.

He ordered pounded yam with ẹ̀fọ́ rírò and a bowl of fresh fish, orísirísi-assorted meats, and goat meat on the side. He also ordered a sweating Star Lager for himself and a Coke for Rọ́lákẹ́. The ẹ̀fọ́, fresh and green ṣọkọ leaves, was loaded with shrimp and other seafood. The aroma made Rọ́lákẹ́ drool as they brought the dishes to the table. She ordered jollof rice and dòdò but he insisted Rọ́lákẹ́ should join him in the pounded yam feast, swearing this was the best restaurant in the whole city for ẹ̀fọ́ rírò. Rọ́lákẹ́ conceded and washed her hands to join him.

They brought her two wraps of hot pounded yam and more plates of meat. She shed her shyness and enjoyed every morsel. The man did not engage in conversation while they were eating, he wanted both of them to enjoy the meal. Rọ́lákẹ́ only ate like this during festivals or ceremonies back home. Actually, never like this. The best parts of the meat would have long gone to the older people, more to the men than to the women.

They finished and he paid. As they walked to the car, the man invited Rọ́lákẹ́ to his residence. He said he was alone and didn’t have many friends. “Kò dáa kéyàn máa dá nìkan gbé.” He said he missed his family, his daughters Fadékẹ́ and Oyin, 9 and 6. He talked of how smart they were, just like their mother. Their mother worked for an oil company, AGIP, in Lagos. She, too, was a graduate of the University of Ibadan. The guest house was cool and nicely furnished. The draperies were heavy and looked very expensive. He said a cleaning woman came in every day to clean even though the place was hardly dirty. The bedroom door was ajar. Rọ́lákẹ́ could see the bedroom from the living room. The bed was neatly made and from a distance she could see the sheets were of high quality. It did look like a guest house, a temporary abode. There were no photographs, books, or any personal possessions. The refrigerator had beer, stout, Coke, Fanta, and a few bottles of Shandy and malt. Rọ́lákẹ́ joined the man in the kitchen where he had opened the fridge to pull out some drinks, Gulda for him, and Malta for her. The kitchen looked as if no one had ever cooked there. All the appliances were new-clean, and the pots and pans looked as if someone just bought them from the store. They went back to the sitting room. Rọ́lákẹ́ who had been enjoying the coolness of the room was now beginning to feel chilly. She shrank her body and hugged herself. He noticed and came to sit close to her, putting his arm around her midriff.

“What do you want to do after you graduate?”

She took some time answering his question.

“Maybe you could continue and get your Ph.D. and become a Biology lecturer.” Such a thought had never entered Rọ́lákẹ́’s head. All her professors were male and there were just a few girls in her Biology class.

“Yes,” but I had never thought of becoming a lecturer.

“Why?”

“I don’t know any female lecturers.”

“Of course, you can. I always tell my daughters this. They can study anything they want and be anything they want. My sisters were deprived of university education because our father thought they should stop at high school and get married. He said their husbands will take care of the rest. One of my sisters made Grade 1 but never got the opportunity to go to university. Bàbá asked her to get married after School Cert. She did and he set her up in business. She’s doing well, but

I’ve always wondered what such a brilliant person could have become. I’m not as brilliant as she is. I made Grade 2 and attended Ìbàdàn.”

His father was in the transport business. He owned fleets of long-distance cars and buses. For him, higher education was for boys only.

He asked Rọ́lákẹ́ about her family. His mother was the first wife of his father, so was Rọ́lákẹ́’s mother. He was the third child of his mother but the fifth of the nine children of his father. Rọ́lákẹ́ was the first child of both her mother and father. Rọ́lákẹ́ said her father married a second wife who had remained barren. She blamed this on Rọ́lákẹ́’s mother and called her mother a witch. Báyọ̀ smiled.

He held her hand and drew closer, gently stroking her right breast from the back. She suddenly grew very furious and pulled away. She was surprised at her own anger. The man was handsome. His skin looked like black velvet to her. His round glasses gave him an air of intelligence, as Rọ́lákẹ́ was partial to intelligent men. His manners were respectful and he was kind to her. He had done nothing to offend her. She had encouraged his flirtations because she secretly thought she might finally solve her problem. Rọ́lákẹ́ was a virgin, and she hated it.

“Kí ló dé?” Báyọ̀, asked, taken aback by her rejection and anger.

“I’m not that kind of girl.”

“What kind of girl? I won’t waste my time with that kind of girl.”

He tried again, and she slapped his hand. In a very cold voice, she asked to be dropped off on campus. Báyọ̀ saw the fury on her face and quietly picked up his car keys.

“Look, I won’t do anything you don’t want to. I like you. You are a smart and pretty girl. Here is my card. You can visit me anytime you want.”

She took the card and dropped it in her bag and they left the apartment. He held the front door open for her and did the same for the car.

“Kíló n bí ẹ nínú toyi? I will never force you to do anything. You don’t have to be angry.” Rọ́lákẹ́ stayed mute. She was still angry. She did not say a single word during the long drive to the campus. He, too, kept quiet. Rọ́lákẹ́ had been planning to lose her virginity for some time. She had been reading about sex, and listening to her friend and roommate, Ṣèyí, regaling her about her sexual adventures with a lecturer in Architecture Department. Rọ́lákẹ́ knew him but had never spoken to him. He was a very tall man who was said to be from some West African country. Rumor had it that his wife left him to go back to their country. Ṣèyí said they had sex in motels in town and sometimes in his office. He had never taken her to his house in Staff Quarters, and she didn’t care. “It’s not as if I want to marry him. It’s a part of my education to learn about sex. The young boys think they’ve won a prize when they have sex with you. They

tell their friends, or they change their behavior after sleeping with you. We have sex on the table in his office, or standing up against the wall. You could hear people walking and talking in the corridor. And you know what he did the last time? I have never seen or heard anything like that. He asked me to sit on the table, pulled a chair and put his mouth on my òbò. Ó bẹ̀rẹ̀ sí jòbò mi. I was shocked and I tried to push him away, but he held my hands firmly, and pushed his tongue deep and then started doing something to my clitoris. Ọ̀rẹ́ mi, I almost fainted from pleasure,” as Ṣèyí dramatically rolled her eyes in her head.

“It’s called cunnilingus,” Rọ́lákẹ́ said.

“How do you know what it is called? You are a virgin!” her friend exclaimed.

“Because I read about sex.” Rọ́lákẹ́ had been checking out books from Hezekiah Olúwásanmí Library, another place on campus she dearly loved. She took out books on Biology and various subjects of interest from the library, but she only checked out her sex books from Mrs. Okeke, an older female librarian. She was too embarrassed to take out such books from male librarians. The woman was always pleasant to her, but with a knowing look on her face.

Rọ́lákẹ́ had always thought her friend was slightly promiscuous but she enjoyed Ṣèyí’s sex tales. She, too, was a virgin when she entered the university, but she said she was determined to do something about it. She told Rọ́lákẹ́ of the sexual life of her brother, Wọlé, and his wife Yétúndé. They both graduated from Ifẹ̀ with degrees in Computer Science. They did everything together on campus, studied together, went to the same parties. In fact, they were like twins on campus. But they never had sex. She was a virgin, something that pleased Wọlé greatly, and made him pay extra attention to Yétúndé. They got married the year they graduated and settled in Lagos with great jobs. After their second child, two boys in quick succession, their marriage ran into trouble.

“Why?” Rọ́lákẹ́ wanted to know.

“She didn’t want to have sex with him anymore. She moved to another room and rejected all his advances,” Ṣèyí said. Ṣèyí was not even aware there was a problem in their marriage until one evening when she was spending her holiday with them. She and her brother went out to run an errand and stopped in the house of a woman in Àpápá. She was a nurse in the Navy and she was her brother’s girlfriend. Even though she was polite to the woman, when she got to the car, she was very angry with her brother for being unfaithful to Yétúndé, and for exposing her to his bad behavior. That was when her brother told her the sexual difficulty in his marriage. “We have not had sex for over six months. It’s a cold war between us. Kíni kí nwá ṣe?” Seyi thought about it for some time and decided she was going to learn about sex experientially, as she told Rọ́lákẹ́. On campus.

There was a time in the past semester when Rọ́lákẹ́ came close to losing her virginity. She met Táyọ̀ who was studying Food Technology. He was in his final year and Rọ́lákẹ́ thought he would at least be a little more mature. They both loved movies and went to Oduduwa Hall regularly to see British and American movies. They particularly shared a fondness for James Bond movies. She also liked romantic movies, but Tayo was not keen. She went to the movies by herself at times, and felt uncomfortable watching sex scenes when they were together. They also saw some plays, one of which was Soyinka’s Opera Wonyosi. It was the second time the play was staged in Oduduwa Hall. Rọ́lákẹ́ missed an earlier production the previous year. She and Táyọ̀, like most students, sat at the upper levels of the theater, in the back. Those with expensive tickets sat at the lower levels near the stage. The hall had a capacity for 1,500 people but curiously, there were some empty rows between these two groups, the haves and have nots. Rọ́lákẹ́ thought of those sitting closer to the stage as the bourgeoise, that class of people she’d been learning about in her Marxist group, and the rest of them at the back as the masses. Just before the play started, the Great Man himself, popularly known as Kongi, stepped on the stage and made a short speech in his stentorian voice, after which he asked everybody to move down and closer, upgrading the viewership of the masses. The students all clapped and noisily rushed to the empty seats. To Rọ́lákẹ́, it was a mini revolution, exactly what Nigeria needed. She and Tayo discussed Ṣóyínká’s biting satire in Opera Wónyòsi, of Nigeria’s military rulers’ lack of vision, corruption and wastefulness. After the shows at Odùduwà Hall, Rọ́lákẹ́ and Táyọ̀ often strolled leisurely around campus, admiring Ifẹ̀’s beautiful architecture. Sometimes, they sat in the outdoor amphitheater behind Oduduwa Hall. If it was not too dark they walked all the way to the Botanical Gardens, sitting on one of the benches, or trying to identify the flora around them. It was said that one student, not ever having seen such gorgeous horticulture, swore he would come back as a plant in the Botanical Gardens of the University of Ifẹ̀ in his next life. Rọ́lákẹ́ didn’t mind that Báyọ̀ kissed her or touched her breasts. There was even a time he dipped his hands into her pants and touched her vagina. It was as if someone poured some liquid soap between her thighs. She loved the smell coming from there. She saw the bulge in his trousers and pulled his hand away. He looked as if he was in pain.

One evening, she went to visit him in his room, which he shared with four other boys. He knew she was coming. The usually boisterous room was quiet. He was alone and was wearing his underpants. Instead of sitting her on the chair near his bed, he asked her to join him on the bed. She did. He started taking off her clothes with urgency. Rọ́lákẹ́ could see and feel the big bulge. He was trying to undo her bra but was having difficulty. “Duro, mii ti ready,” Rọ́lákẹ́ said quietly. She pushed his hands away. He sat up and seemed to be angry. Then he turned to her and said, “Wòó, mo màwon girls tí wọn nii mind. I don’t understand you. Ìgbà wo lo fẹ́ ready.” It was as if someone slapped Rọ́lákẹ́. She didn’t expect this ugly behavior from him. She got up, pulled her dress down, and said with a measure of dignity, “Go to your girls who don’t mind.” She picked up her bag and left. She waited for him to come after her or visit her in her

room in the next few days. He never did. It took her some time to recover because she really liked Táyọ̀ and thought they were building a relationship. She wanted to lose her virginity, but she wanted a boy who wanted more than sex.

Finally, the banker pulled up to the parking lot of Mọ́rèmí Hall and Rọ́lákẹ́ collected her bags of condiments from his boot. He stood for some time and contemplated her as she was picking up the bags.

“O.K. Rọ́lákẹ́. Má bínú. I’m sorry if I offended you.” He smiled and said “Let us be friends.” She did not smile back. She bid him goodbye and climbed the stairs at the Porters’ Lodge leading to the corridor of G & H block.

She stayed angry for some time until she saw her friend and told her about the incident. Predictably, she asked “Kíló ṣe ẹ́? What did he do wrong? He wants you, you want him. Àbí? And he treated you nicely. Kíló wá dé?”

“I don’t know,” was all she could say..

The answer did not come until years later when Rọ́lákẹ́ who had become an accountant in Lagos was buying her own Mercedes Benz. It was a used V-boot. But she loved it. It occurred to her that her anger against the Mercedes man was because of his car, not because of anything he did. In fact, she thought if he had been driving another kind of car that day, she would have yielded her virginity to him. Mercedes Benz was the car her father lusted after and couldn’t get. To him, it was the symbol of success and status in the world, which he felt he never achieved. Rọ́lákẹ́ associated the car with her father’s rage and unjustified anger. Part of her hated the car, and so she could not bring herself to sleep with a man who drove such a car.

Rọ́lákẹ́ climbed into her Mercedes Benz and adjusted her sunglasses. Her car’s leather seats were a little worn, but she loved the comfortable interior. The speakers were excellent. It was 6p.m. when she finished work at her accounting firm in Marina. She slid Ebenezer Obey’s cassette into the player and blasted “À Ńjáde Lọ Leni”, then turned the air condition to the highest level. She did not even notice the congestion on Ikorodu road as she headed home from Marina to her family in Ìkẹjà.

Bunmi Fatoye-Matory is a columnist, essayist, and writer of fiction. A graduate of Great Ife (Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria), University of Ibadan, and Harvard University, she enjoys reading, traveling, meeting people, and learning about Yoruba cosmology. A convert to Yoruba traditional religion, she is an initiated Osun devotee. She lives with her family in Durham, North Carolina, USA..

Very nice article and straight to the point. I am not sure if this is really the best place to ask but do you guys have any ideea where to employ some professional writers? Thanks 🙂

Aw, this was a very good post. Spending some time and actual effort to create a good article… but what can I say… I hesitate a lot and don’tseem to get anything done.

Hello there! I simply want to offer you a huge thumbs up for the great info you have got here on this post. I am coming back to your blog for more soon.

Enjoyed every bit of your blog article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Hmm is anyone else having problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to figure out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any feed-back would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks for some other fantastic post. Where else may just anybody get that kind of information in such an ideal means of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at the search for such information.

ivermectin tablets for humans – stromectol xr stromectol over the counter

Great, thanks for sharing this blog article.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

Really informative blog post.Really thank you! Awesome.

Thanks for the blog post.Much thanks again. Cool.

Fantastic article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

Muchos Gracias for your article.Much thanks again. Awesome.

wow, awesome blog article.Much thanks again. Cool.

I think this is a real great blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

This is one awesome blog post. Want more.

Hi, I do think this is an excellent blog. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may revisit once again since i have saved as a favorite it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide other people.

I do agree with all the concepts you’ve presented in your post. They’re really convincing and will definitely work. Still, the posts are very brief for beginners. May you please extend them a bit from subsequent time? Thank you for the post.

is green coffee bean extract safe WALSH ENDORA

You are going to likely end up spending on the upwards of 40 to 60 hours a weekat your new job.

Really enjoyed this blog article. Keep writing.

Its fantastic as your other blog posts : D, thankyou for putting up.

Thank you for your article.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Hi. Such a nice post! I’m really enjoy this. It will be great if you’ll read my first article on AP!) should employers be required to pay men and women the same salary for the same job essay

Enjoyed every bit of your blog post. Much obliged.

Hey there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the imagesaren’t loading properly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue.I’ve tried it in two different internet browsers and both show the same results.

It’s actually a great and helpful piece of info. I am glad that you just shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

stromectol online ivermectin oral 0 8 – stromectol liquid

What’s up friends, its enormous article on the topic of teachingand fully explained,keep it up all the time.

doxycycline in spanish doxycycline uk online doxycycline monohydrate vs doxycycline hyclate doxycycline hyclate what is it used for

Very good article.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Aw, this was a very nice post. Finding the time and actual effort to generate a very good articleÖ but what can I sayÖ I procrastinate a whole lot and don’t seem to get anything done.

Nice respond in return of this matter withgenuine arguments and describing everything concerning that.

Really informative blog article.Much thanks again. Want more.

It’s fantastic that you are getting thoughts from this article as well as from our discussion made at this place.

I need to to thank you for this excellent read!! I definitely enjoyed every little bit of it. I have you book-marked to look at new stuff you post…

constantly i used to read smaller content that also clear their motive, and that is also happening with this piece of writing which I am reading now.

… [Trackback][…] Find More here on that Topic: bellepetitedesign.com/favorite-beauty-products-of-all-time/ […]

Hello there! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with SEO?I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywordsbut I’m not seeing very good results. If you know of any pleaseshare. Thanks!

I have recently started a site, the information you provide on this web site has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.

Hey would you mind letting me know which hosting company you’re working with? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you recommend a good hosting provider at a honest price? Cheers, I appreciate it!

you’ve gotten an amazing blog here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my weblog?

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made sure nice points in options also.

Somebody essentially help to make seriously articles I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your website page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to make this particular publish extraordinary. Fantastic job!

Howdy! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with SEO? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good results. If you know of any please share. Kudos!

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you make this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz answer back as I’m looking to construct my own blog and would like to find out where u got this from. thank you

Great blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog jump out. Please let me know where you got your theme. With thanks

I like what you guys are up also. Such smart work and reporting! Carry on the superb works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my website 🙂

In the grand scheme of things you get an A just for hard work. Where exactly you actually lost us was first on all the specifics. You know, as the maxim goes, the devil is in the details… And it could not be much more true here. Having said that, allow me say to you what exactly did work. The article (parts of it) is actually rather convincing which is possibly why I am taking an effort in order to opine. I do not really make it a regular habit of doing that. Next, although I can certainly see the leaps in logic you make, I am not necessarily sure of just how you appear to connect your details which inturn help to make the actual final result. For right now I will subscribe to your issue however trust in the near future you connect the facts much better.

Study on to find out how to read NBA odds and find outhow NBA odds perform.

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of info. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks again for the blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Hey there! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone4! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts!Keep up the superb work!

Fantastic post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

I am often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

My goal is to bless everyone’s timeline w/ the 100 cute animal likes Iclick on . Y’all are flooding my timeline w/ half naked girls

Thanks again for the article.

Very informative post.

whoah this blog is great i love reading your posts. Keep up the great work! You know, a lot of people are looking around for this information, you could aid them greatly.

A big thank you for your post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Im grateful for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

with hackers and I am looking at alternatives for another platform. I would be great if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

A big thank you for your blog.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Very good article post.Much thanks again. Cool.

Im thankful for the article.Really looking forward to read more.

Im grateful for the blog post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Thank you for your post. Great.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Enjoyed every bit of your blog article.Much thanks again. Want more.

ivermectin coupon ivermectin 1 can i use ivermectin on my goats which is a better all around dewormer valbazen or ivermectin for goats

Muchos Gracias for your article post.Thanks Again.

Im thankful for the blog post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Im obliged for the blog post.Thanks Again. Want more.

Heya i’m for the primary time here. I found this board and I to find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I’m hoping to give one thing back and help others like you aided me.

I appreciate you sharing this blog. Will read on…

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Thanks a lot for the blog post.Much thanks again. Cool.

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have truly enjoyed browsing your blog posts. After all I will be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again very soon!

Great post. I was checking continuously this blog and I am impressed!Very helpful info particularly the last part I care for such info much. I was looking for this certain information for a very long time.Thank you and best of luck.

Some truly nice stuff on this website , I love it.

Hey, you used to write excellent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring… I miss your super writings. Past few posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Appreciate you sharing, great post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

generic ivermectin stromectol – ivermectin 1 cream 45gm

I really enjoy the article. Much obliged.

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I am very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i am looking forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a mail?

generic vardenafil us – vardenafil generic vs brand name order vardenafil

Very neat blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Hello! I could have sworn Iíve been to this blog before but after going through some of the articles I realized itís new to me. Anyways, Iím certainly pleased I discovered it and Iíll be bookmarking it and checking back regularly!

tamoxifen alternatives alternative to tamoxifen – tamoxifen benefits

Thông Tin, Sự Kiện Liên Quan Tiền Đến Trực Tiếp đá Bóng Nữ Giới cá mực hầm mậtĐội tuyển nước Việt Nam chỉ cần thiết một kết quả hòa có bàn thắng nhằm lần thứ hai góp mặt trên World Cup futsal. Nhưng, nhằm thực hiện được điều này

I think this is a real great blog article.Really thank you! Cool.

Muchos Gracias for your post.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Muchos Gracias for your post. Really Cool.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog article.Thanks Again. Cool.

Im obliged for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

Thanks for the blog.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Thanks , I have just been searching for info approximately this subject for ages and yours is the best I’ve discovered so far. But, what concerning the conclusion? Are you certain concerning the source?

Having read this I believed it was really enlightening. I appreciate you taking the time and energy to put Judi Slot Online this information together. I once again find myself spending a significant amount of time both reading and commenting

This is one awesome post.Thanks Again.

A round of applause for your blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

I think this is a real great article.Much thanks again. Cool.

bagcilar escort[…]always a massive fan of linking to bloggers that I adore but dont get a whole lot of link like from[…]

Appreciate you sharing, great article.Thanks Again. Keep writing.

This piece of writing is truly a nice one ithelps new net viewers, who are wishing in favor of blogging.

Major thankies for the post.Really thank you! Will read on…

Very good write ups, Many thanks! lisinopril

I always was concerned in this subject and stock still am, appreciate it for putting up.

Hi there i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anyplace, when i read this post i thought i could also create comment due to this good piece of writing.

Thanks-a-mundo for the post. Much obliged.

Perfectly written articles, thank you for entropy. «The earth was made round so we would not see too far down the road.» by Karen Blixen.

This is one awesome blog post.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

Great post however , I was wanting to know if you couldwrite a litte more on this topic? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit further.Appreciate it!

Hey, thanks for the article post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

My partner and I stumbled over here by a different website andd

thought I mght as well check things out. I like what I

see so noow i am following you. Lookk forward to looking ovger your web pagee again. https://menbehealth.Wordpress.com/

Enjoyed every bit of your article.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Ahaa, itss fastidious discussion concerning this paragraph here at thiis web site, I

have read all that, so now me also commenting here. https://Njspmaca.in/2025/03/18/acesse-o-site-de-apostas-20bet-a-app-que-garante-uma-experiencia-desportiva-excepcional-para-os-aficionados-por-jogos-repleta-de-varias-competicoes-e-palpites/

Some really fantastic information, Glad I found this. “Civilization is a transient sickness.” by Robinson Jeffers.

Very neat blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Say, you got a nice article post. Really Cool.

I appreciate you sharing this blog article.Really thank you!

That is a very good tip especially to those new to the blogosphere. Brief but very precise info… Appreciate your sharing this one. A must read post!

If you would like to take much from this post then you have to applysuch methods to your won blog.

Very informative and well-written, thanks!

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog post.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Great, thanks for sharing this post.Really looking forward to read more.

Hello, its good piece of writing on the topic of media print,we all be aware of media is a wonderful source of data.

Thank you for your post.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Thank you for another wonderful article. Where else could anyone get that kind of info in such an ideal way of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I am on the look for such info.

Resume plastics engineer ma shark essaysUYhjhgTDkJHVy

Fantastic post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

hydroxychloroquine coronavirus chloroquine death hydroxychloroquine 200

Más de 40 pixar terreno para vacaciones de primavera en chalcid wasp whakatāne

Hello, I read your blog on a regular basis. Your story-telling style is awesome, keep it up!

Superb postings. Appreciate it. hydrochlorothiazide

Just about all of whatever you claim happens to be supprisingly accurate and it makes me wonder the reason why I had not looked at this with this light previously. This piece really did switch the light on for me as far as this subject matter goes. Nevertheless at this time there is actually just one factor I am not necessarily too cozy with so whilst I attempt to reconcile that with the actual core theme of the position, allow me observe what all the rest of your readers have to say.Well done.

Really enjoyed this post, how can I make is so that I receive an email every time you publish a new article?

Hello colleagues, how is all, and what you desireto say about this article, in my view its really amazing for me.

I am now not certain the place you are getting your info, however good topic. I needs to spend some time finding out much more or figuring out more. Thanks for wonderful information I used to be searching for this information for my mission.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Say, you got a nice post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

I appreciate you sharing this blog article. Really Great.

Thanks a lot for the blog post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Thanks so much for the blog article. Awesome.

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

Fantastic post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

I have read several good stuff here. Definitely value bookmarking for revisiting.

I surprise how a loot effort yoou place to create this sort of wonderful informative wweb site. https://Worldwiderecruiters.ca/employer/arndt/

Excellent blog you have here.. Itís difficult to find quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Swaps are executed instantly—no waiting time!

I all the time used to read post in news papers but now as I am

a user of net so from now I am using net for articles, thanks to

web.

Thank you ever so for you blog.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Thank you for your article post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Very good blog.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Major thanks for the blog post. Really Cool.

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google,and found that it is really informative. I am going to watch out for brussels.I’ll be grateful if you continue this in future. Numerous people will be benefited fromyour writing. Cheers!

Enjoyed every bit of your article post.Much thanks again. Cool.

It’ѕ aⅽtually a cool and helpful piece oof info.I’m glad that yyou simply shared this helpful info wіth us.Please stay us up to date like this. Thankѕ for sharing.my homepagе: ford mustang for sale

Great post. I’m going through a few of these issues as well..

My brother recommended I might like this blog.He was entirely right. This post actually made my day. You can not imagine simplyhow much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

I think this is a real great blog post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Great blog article. Cool.

Enjoyed every bit of your blog.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Major thanks for the blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

This is nicely expressed. .how to write a nonfiction essay online college homework help phd writer

I not to mention my friends have already been reviewing the best secrets located on the website then all of the sudden I had a terrible suspicion I never thanked the website owner for them. All the boys had been so stimulated to study them and now have quite simply been taking pleasure in those things. Thank you for genuinely very kind and for settling on such cool guides most people are really eager to learn about. My very own honest apologies for not expressing appreciation to you sooner.

Looking forward to reading more. Great post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

I really like and appreciate your article.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Navigating Insolvency Risks

Huge win for anyone active on multiple blockchains.

The real-life scenarios were super relatable and useful.

I am so grateful for your blog.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

Wish I had this guide when I first started farming.

Im obliged for the blog article.Much thanks again.

Great, thanks for sharing this blog article.Really thank you!

This guide made cross-chain movement feel so much easier.

Thanks again for the blog.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Really enjoyed this article post.Really thank you! Want more.

Very neat article.Thanks Again. Want more.

I really liked your article post.

Using the bridge opened up a whole new set of dApps.

Wish I had this guide when I first started farming.

Thank you for your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s reallyinformative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll appreciate if you continue this in future.Numerous people will be benefited from your writing.Cheers!

I really liked your blog post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Im thankful for the article post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

I wanted to thank you for this very good read!! I definitely enjoyed every bit of it. I’ve got you bookmarked to look at new stuff you post…

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular post! It’s the little changes that will make the most important changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

Im grateful for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Thank you for your blog post. Much obliged.

Thanks for the article. Really Great.

Thank you for your blog post.Really thank you! Great.

Hurrah! At last I got a blog from where I can genuinely take helpfulfacts regarding my study and knowledge.Take a look at my blog post; eczema healsLoading…

Very good blog article.Thanks Again. Great.

I really liked your article post.Much thanks again. Cool.

online paper editingproposal writing services

Im obliged for the blog post. Great.

login totocc

You made a few good points there. I did a search on the subject matter and found most folks will consent with your blog.

I read this post completely on the topic of the comparison ofmost recent and previous technologies, it’s awesome article.Feel free to surf to my blog post – 카지노사이트

Hey! I just wanted to ask if you ever have anyproblems with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing many months of hard work due to no databackup. Do you have any methods to preventhackers?my blog post – teenager smoking

Major thankies for the blog article.Really thank you! Much obliged.

Major thankies for the article.Thanks Again. Will read on…

PUFF BAR WEED[…]The details mentioned within the write-up are several of the ideal out there […]

It’s hard to search out educated folks on this matter, but you sound like you understand what you’re speaking about! Thanks

It¦s really a great and useful piece of info. I am happy that you simply shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

This paragraph is in fact a pleasant one it assists new net users, who are wishing for blogging.

casino olympe: olympe – olympe casino cresus

Muchos Gracias for your post. Fantastic.

Achetez vos kamagra medicaments: acheter kamagra site fiable – kamagra livraison 24h

brians club

ankara escort

undefined

kamagra gel: Kamagra pharmacie en ligne – kamagra pas cher

Kamagra Oral Jelly pas cher: Acheter Kamagra site fiable – Kamagra Commander maintenant

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique pharmafst.com

kamagra livraison 24h: kamagra livraison 24h – kamagra en ligne

Acheter Cialis: Tadalafil achat en ligne – Cialis en ligne tadalmed.shop

kamagra livraison 24h: kamagra pas cher – acheter kamagra site fiable

pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique: pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne livraison europe pharmafst.com

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es: Meilleure pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance pharmafst.com

Kamagra Commander maintenant: Acheter Kamagra site fiable – kamagra en ligne

kamagra gel: Achetez vos kamagra medicaments – achat kamagra

Tadalafil achat en ligne: Tadalafil achat en ligne – cialis prix tadalmed.shop

kamagra pas cher: kamagra oral jelly – acheter kamagra site fiable

Awesome blog post. Want more.

Hello just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the images aren’t loadingproperly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue.I’ve tried it in two different browsers and both show the same outcome.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article.Really looking forward to read more.

I truly appreciate this blog post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

acheter kamagra site fiable: kamagra gel – kamagra oral jelly

Thanks again for the article. Much obliged.

Cialis sans ordonnance 24h: Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher – cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

Im thankful for the article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Helpful information. Fortunate me I discovered your web site by accident, and I am shocked why

this tist of fate did not happened earlier! I bookmarked

it. https://zapbrasilempregos.com.br/employer/witherspoon/

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican rx online – Rx Express Mexico

Alpaca Finance

Alpaca Finance

mexico pharmacy order online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – Rx Express Mexico

RenBridge

mexico pharmacy order online: mexican rx online – mexican rx online

canadian pharmacy uk delivery: Express Rx Canada – canadian family pharmacy

We are looking for some people that might be interested in from working their home on a full-time basis. If you want to earn $200 a day, and you don’t mind writing some short opinions up, this might be perfect opportunity for you!

Alpaca Finance

canadian pharmacy online store: Express Rx Canada – safe canadian pharmacies

mexican rx online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexican rx online

RenBridge

Alpaca Finance

Alpaca Finanace

escrow pharmacy canada: Buy medicine from Canada – canadian mail order pharmacy

We are looking for experienced people that are interested in from working their home on a full-time basis. If you want to earn $500 a day, and you don’t mind developing some short opinions up, this might be perfect opportunity for you!

indian pharmacy online: indian pharmacy online – medicine courier from India to USA

Very informative article post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

indian pharmacies safe MedicineFromIndia indian pharmacy online

mexican online pharmacy: RxExpressMexico – RxExpressMexico

northwest canadian pharmacy: Buy medicine from Canada – canadian pharmacy ratings

RxExpressMexico RxExpressMexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

RxExpressMexico: mexico pharmacy order online – mexican rx online

canadian pharmacy prices: Express Rx Canada – canadian neighbor pharmacy

«Вот тебе все и объяснилось, – подумал Берлиоз в смятении, – приехал сумасшедший немец или только что спятил на Патриарших. раскрутить сайт самостоятельно – Это уж как кому повезет, – прогудел с подоконника критик Абабков.

canadapharmacyonline com Express Rx Canada prescription drugs canada buy online

mexican drugstore online: buying prescription drugs in mexico – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican rx online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – Rx Express Mexico

Very good article post.Thanks Again. Cool.

RenBridge Finanace

RenBridge Finanace

Alpaca Finanace

Rhinobridge

– Виноват, – мягко отозвался неизвестный, – для того, чтобы управлять, нужно, как-никак, иметь точный план на некоторый, хоть сколько-нибудь приличный срок. вивус Но я однажды заглянул в этот пергамент и ужаснулся.

И вот два года тому назад начались в квартире необъяснимые происшествия: из этой квартиры люди начали бесследно исчезать. добавить сайт в поиск И вот проклятая зелень перед глазами растаяла, стали выговариваться слова, и, главное, Степа кое-что припомнил.

Берлиоз тотчас сообразил, что следует делать. Причины пожелтения пластиковых окон – И, сузив глаза, Пилат улыбнулся и добавил: – Побереги себя, первосвященник.

Im thankful for the article.Really thank you! Cool.

pin up azerbaycan: pin up casino – pin up az

A round of applause for your post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

quick swap

quick swap

quick swap

quick swap

When some one searches for his vital thing, so he/she needs to be available that in detail, so that thing is maintained over here.

В самом деле, ведь не спросишь же его так: «Скажите, заключал ли я вчера с профессором черной магии контракт на тридцать пять тысяч рублей?» Так спрашивать не годится! – Да! – послышался в трубке резкий, неприятный голос Римского. апостиль о несудимости В саду было тихо.

вавада зеркало: вавада – vavada casino

Дело в том, что в этом вчерашнем дне зияла преогромная черная дыра. нотариус Пестрецова – Эге-ге, – воскликнул Иван и поднялся с дивана, – два часа, а я с вами время теряю! Я извиняюсь, где телефон? – Пропустите к телефону, – приказал врач санитарам.

пин ап казино: пинап казино – пинап казино

«Совершенно верно!» – подумал Степа, пораженный таким верным, точным и кратким определением Хустова. нотариус Зябликово Последние же, Вар-равван и Га-Ноцри, схвачены местной властью и осуждены Синедрионом.

пин ап зеркало: pin up вход – пинап казино

Thank you for your post.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Там ожидавшему его секретарю он велел пригласить в сад легата легиона, трибуна когорты, а также двух членов Синедриона и начальника храмовой стражи, ожидавших вызова на нижней террасе сада в круглой беседке с фонтаном. Шплинты Наобум позвонили в комиссию изящной словесности по добавочному № 930 и, конечно, никого там не нашли.

pin up azerbaycan: pin up azerbaycan – pin-up casino giris

И все из-за того, что он неверно записывает за мной. ремонт пола Что касается зубов, то с левой стороны у него были платиновые коронки, а с правой – золотые.

pin up az: pin up casino – pinup az

bokep siskaeee

pin up azerbaycan: pinup az – pin up casino

Hey, thanks for the blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

pin-up casino giris: pinup az – pin-up casino giris

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular article! It is the little changes which will make the most significant changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

Appreciate you sharing, great post.

пин ап зеркало: pin up вход – pin up вход

A round of applause for your article.Really thank you! Really Cool.

Private chauffeur for Normandy Tours

Private car service Paris

vavada: вавада официальный сайт – вавада зеркало

Enjoyed every bit of your article.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

пинап казино: пинап казино – пин ап зеркало

Very neat article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

pinup az: pin up azerbaycan – pin up casino

Great, thanks for sharing this article.Thanks Again. Will read on…

вавада официальный сайт: vavada casino – вавада зеркало

I needed to thank you for this wonderful read!! I definitely loved every bit of it. I have got you saved as a favorite to look at new things you postÖ

вавада зеркало: vavada – вавада официальный сайт

I really liked your blog article.Thanks Again. Want more.

vavada casino: vavada вход – vavada

vavada вход: вавада официальный сайт – vavada

pin-up: pin up – pin-up

pinup az: pin up casino – pin up azerbaycan

Thanks for another excellent article. The place elsemay just anybody get that type of information in such a perfect way of writing?I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at the look forsuch info.

bokep milf

bokep viral bu guru salsa

vavada вход: vavada вход – вавада

Appreciate it for helping out, great information.

vavada casino: vavada casino – вавада официальный сайт

Very neat blog post. Much obliged.

Scorpions Lolita Girls Fucked Chrestomathy Pthc cp offline forum xtl.jp/?pr

вавада официальный сайт: vavada вход – вавада зеркало

пин ап казино официальный сайт: пин ап вход – пин ап казино

candy ai girlfriend

pin up az: pin up casino – pin up az

pin up az: pin up – pin up azerbaycan

I am so grateful for your blog.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Really enjoyed this post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Thanks again for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Wow, great article.

Fantastic blog article. Great.

provigil generic modinafil med provigil dosage provigil medication

This is one awesome post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

online Cialis pharmacy: affordable ED medication – secure checkout ED drugs

Thanks so much for the blog. Much obliged.

same-day Viagra shipping: safe online pharmacy – Viagra without prescription

Casino en ligne

Really enjoyed this blog.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

discreet shipping ED pills: secure checkout ED drugs – reliable online pharmacy Cialis

doctor-reviewed advice: modafinil legality – modafinil 2025

safe modafinil purchase: doctor-reviewed advice – modafinil 2025

verified Modafinil vendors: modafinil legality – buy modafinil online

cheap Cialis online: best price Cialis tablets – order Cialis online no prescription

legit Viagra online: best price for Viagra – legit Viagra online

doctor-reviewed advice: doctor-reviewed advice – verified Modafinil vendors

legal Modafinil purchase: modafinil legality – safe modafinil purchase

reliable online pharmacy Cialis: order Cialis online no prescription – best price Cialis tablets

discreet shipping ED pills: generic tadalafil – cheap Cialis online

http://modafinilmd.store/# modafinil legality

cheap Cialis online: Cialis without prescription – affordable ED medication

Cialis without prescription: affordable ED medication – order Cialis online no prescription

buy modafinil online: safe modafinil purchase – modafinil pharmacy

Viagra without prescription: no doctor visit required – trusted Viagra suppliers

amoxicillin 500mg capsules: amoxicillin 500mg cost – Amo Health Care

Muchos Gracias for your article.Thanks Again. Great.

where can you get amoxicillin: Amo Health Care – Amo Health Care

Very good article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

Amo Health Care: Amo Health Care – can you buy amoxicillin over the counter in canada

Really informative article.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

I love it when folks get together and share ideas.Great blog, continue the good work!

all things poker

amoxicillin discount coupon: amoxicillin cost australia – Amo Health Care

can you buy prednisone over the counter: prednisone 1 tablet – PredniHealth

A round of applause for your post. Awesome.

I really enjoy the blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

I am so grateful for your article.Really thank you! Will read on…

Escort mersin mersin escort bayan

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog article.Really thank you! Really Cool.

Thanks a lot for the blog article.Much thanks again. Awesome.

How to Use DeFiLlama: A Practical Guide for Navigating DeFi Analytics

I am so grateful for your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Didn’t know where my yield was until I found DefiLlama. Game changer.

DefiLlama = DeFi sanity.

Seriously, thank you to the team behind DefiLlama.

Renbridge

RenBridge Dashboard

Bridge ETH on RenBridge

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your blog and check once more here frequently. I am relatively certain I’ll learn lots of new stuff right here! Good luck for the following!

cialis 20 mg price walmart: what happens if you take 2 cialis – cialis or levitra

Thanks-a-mundo for the article.Really thank you! Cool.

magnificent issues altogether, you simply won a emblem new

reader. What would you suggest about your put up that you made a few days in the past?

Any sure?

Automatic Gates Near Me

cialis wikipedia: TadalAccess – cialis and melanoma

Say, you got a nice post.Really thank you! Awesome.

how to get cialis prescription online: sublingual cialis – max dosage of cialis

Thanks a lot for the article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

cialis and poppers: Tadal Access – tadalafil from nootropic review

Jonitogel

TSO777 situs login slot online uang asli paling gacor di asia dengan tingkat kemenangan tinggi dan merupakan link daftar situs toto 4d terbaik dengan hadiah togel terbesar.

DefiLlama

Hi are using WordPress for your blog platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and set up my own. Do you need any coding knowledge to make your own blog? Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Really appreciate you sharing this post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

DefiLlama

DefiLlama

Awesome blog post.Much thanks again. Great.

Very good blog post.Really thank you! Great.

I really like and appreciate your article. Keep writing.

Matcha Swap

Matcha Swap

Ну, а колдовству, как известно, стоит только начаться, а там уж его ничем не остановишь. центры переводов в москве Но мучения твои сейчас кончатся, голова пройдет.

Im thankful for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Исчезли пластрон и фрак, и за ременным поясом возникла ручка пистолета. самостоятельное продвижение статьями сайта За квартирным вопросом открывался роскошный плакат, на котором изображена была скала, а по гребню ее ехал всадник в бурке и с винтовкой за плечами.

Thanks so much for the blog post.Thanks Again. Want more.

А ресторан зажил своей обычной ночной жизнью и жил бы ею до закрытия, то есть до четырех часов утра, если бы не произошло нечто, уже совершенно из ряду вон выходящее и поразившее ресторанных гостей гораздо больше, чем известие о гибели Берлиоза. создания сайта с помощью wordpress Полотенца, которыми был связан Иван Николаевич, лежали грудой на том же диване.

Very neat blog post.

A round of applause for your article post. Fantastic.

Через минуту он вновь стоял перед прокуратором. бюро переводов заверение нотариусом Виртуозная штучка! – Умеешь ты жить, Амвросий! – со вздохом отвечал тощий, запущенный, с карбункулом на шее Фока румяногубому гиганту, золотистоволосому, пышнощекому Амвросию-поэту.

Утром за ним заехала, как обычно, машина, чтобы отвезти его на службу, и отвезла, но назад никого не привезла и сама больше не вернулась. нотариальное заверение перевода документов это А тут еще алкоголизм… Рюхин ничего не понял из слов доктора, кроме того, что дела Ивана Николаевича, видно, плоховаты, вздохнул и спросил: – А что это он все про какого-то консультанта говорит? – Видел, наверное, кого-то, кто поразил его расстроенное воображение.

Very neat post.Much thanks again. Really Great.

– А на что же вы хотите пожаловаться? – На то, что меня, здорового человека, схватили и силой приволокли в сумасшедший дом! – в гневе ответил Иван. стоимость нотариального перевод заверения паспорта – Сознавайтесь, кто вы такой? – глухо спросил Иван.

Как первое и второе, так и третье – совершенно бессмысленно, вы сами понимаете. 3 ооо мкк смсфинанс Не нервничайте.

I cannot thank you enough for the article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

Один лунный луч, просочившись сквозь пыльное, годами не вытираемое окно, скупо освещал тот угол, где в пыли и паутине висела забытая икона, из-за киота которой высовывались концы двух венчальных свечей. honda dio af68 воздушный фильтр Коридор с синими лампами, прилипший к памяти? Мысль о том, что худшего несчастья, чем лишение разума, нет на свете? Да, да, конечно, и это.

Он поместился в кабинете покойного наверху, и тут же прокатился слух, что он и будет замещать Берлиоза. воздушный фильтр volvo fh13 Крылья ласточки фыркнули над самой головой игемона, птица метнулась к чаше фонтана и вылетела на волю.

«Здравствуйте! – рявкнул кто-то в голове у Степы. vivus режим работы Москва отдавала накопленный за день в асфальте жар, и ясно было, что ночь не принесет облегчения.

Поднимая до неба пыль, ала ворвалась в переулок, и мимо Пилата последним проскакал солдат с пылающей на солнце трубою за спиной. просрочка смсфинанс Две каких-то девицы шарахнулись от него в сторону, и он услышал слово «пьяный».

I cannot thank you enough for the post.Much thanks again.

– Только не поздно, граф, ежели смею просить; так без десяти минут в восемь, смею просить. регулировка пластиковых окон цена работы за створку москва — Так что же, граждане, простить его, что ли? — спросил Фагот, обращаясь к залу.

Matcha Auto

Its such as you learn my mind! You appear to know so much about

this, such as you wrote the e-book in it or something.

I think that you just can do with some % to power the message house

a little bit, however instead of that, that iss wonderful blog.

An excellent read. I will certainly be back. https://Www.Gmt400.com/members/bill-flores.89539/

Major thankies for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

— Зачем? — продолжал Воланд убедительно и мягко, — о, трижды романтический мастер, неужто вы не хотите днем гулять со своею подругой под вишнями, которые начинают зацветать, а вечером слушать музыку Шуберта? Неужели ж вам не будет приятно писать при свечах гусиным пером? Неужели вы не хотите, подобно Фаусту, сидеть над ретортой в надежде, что вам удастся вылепить нового гомункула? Туда, туда. замена уплотнителя стекла на пластиковых окнах Челнок дёрнулся.

I really enjoy the post.Much thanks again.

– Нас нашли! Ура! Вывалились камни кладки, в темноте открывшейся дыры мелькнула неясная фигура. москитная сетка на пластиковые окна тверь купить И будешь со мной, пока не отпущу.

Заржали, тревожно заметались лошади. москитная сетка антикошка антипыль Сокол радовался, словно сам первым прискакал, всё рассказывал, какие сильные соперники эти тульские и зареченские русы.

В храме Опалуна. москитные сетки на пластиковые окна как снять – Вы знаете, что с того самого дня, как вы в первый раз приехали в Отрадное, я полюбила вас, – сказала она, твердо уверенная, что она говорила правду.

I really like and appreciate your blog article. Really Great.

Но улыбки своей он не утратил и в этом печальном случае, и был смеющеюся Маргаритой допущен к руке. сетка москитная для пластиковых окон своими руками ремонт Тень манит за собой, подводит к двери.

box section stainless steel

Appreciate you sharing, great article.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Arbswap Nova

Appreciate you sharing, great blog.Really thank you! Cool.

Really appreciate you sharing this blog post. Really Great.

Wow, great post.Thanks Again.

Whats Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It positively useful and it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & assist other users like its helped me. Good job.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Приказание Воланда было исполнено мгновенно. Если это тот Силен, мифический, который сатир. Кроме того, он знает, что в саду за решеткой он неизбежно увидит одно и то же.

I dugg some of you post as I thought they were very beneficial very useful

Looking forward to reading more. Great article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

bokep indo hijab

Enjoyed every bit of your blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Really appreciate you sharing this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

Wow, great article.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

Его волнение перешло, как ему показалось, в чувство горькой обиды. Одна группа уже была в сильном подпитии и горланила песню, две вели себя поспокойнее, но тоже не понравились Славке. Ночь оказалась беспросветной, шаг в сторону и тебя не найдут.

I am so grateful for your blog post.Thanks Again.

– Взойдём, и сразу на витки. Русана считала современную пищу более вкусной и здоровой, а мальчишкам нравилась древняя. «Поляк?.

I appreciate you sharing this article post. Cool.

Славка глянул на Тимкины часы: – Всё, время. Однако Аркадию Аполлоновичу подойти к аппарату все-таки пришлось. Не повредили? Несколько грубых голосов вразнобой ответили: – Что им сделается, господин? Дети бога – народ крепкий.

Тут охранник выгнал маленького раба, притворил дверь, громыхнул запорным брусом. Вода обрушилась так страшно, что, когда солдаты бежали книзу, им вдогонку уже летели бушующие потоки. Это страшно трудно делать, потому что исписанная бумага горит неохотно.

Thanks so much for the post.Really thank you! Awesome.

— Бросьте! Бросьте! — кричала ей Маргарита, — к черту его, все бросьте! Впрочем, нет, берите его себе на память. Оркестр человек в полтораста играл полонез. Исчез бесследно нелепый безобразный клык, и кривоглазие оказалось фальшивым.

Сами разбирайтесь. Начался шум, назревало что-то вроде бунта. 76 – Браки совершаются на небесах.

Та мимоходом протянула ему ладошку, словно предложила что-то вкусное. Расскажите мне что-нибудь о самом себе; вы никогда о себе не говорите. Онфим поднялся, оправил своё одеяние, которое напомнило Русане рясу, которые в будни носили православные священники: – Так он про то и глаголет.

В полном смятении он рысцой побежал в спальню и застыл на пороге. Из-за этого день тянулся долго, утомительно. Сейчас он направляется к нам.

This is one awesome article post.

I appreciate you sharing this blog.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Very neat blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Hey, thanks for the blog. Really Cool.

Ero Pharm Fast: Ero Pharm Fast – how to get ed meds online

https://eropharmfast.com/# ed pills for sale

get antibiotics quickly buy antibiotics online uk cheapest antibiotics

Thanks-a-mundo for the article post.Much thanks again. Awesome.

cheapest antibiotics: buy antibiotics online – Over the counter antibiotics for infection

pharmacy online australia: PharmAu24 – Pharm Au24

Looking forward to reading more. Great article post. Keep writing.

buy ed medication: Ero Pharm Fast – best online ed pills

https://biotpharm.com/# buy antibiotics from canada

I cannot thank you enough for the blog post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

ed meds by mail Ero Pharm Fast Ero Pharm Fast

get antibiotics quickly: buy antibiotics – get antibiotics without seeing a doctor

This is one awesome blog post.Thanks Again. Want more.

Over the counter antibiotics for infection: get antibiotics quickly – buy antibiotics

buy antibiotics for uti Biot Pharm get antibiotics without seeing a doctor

cheapest ed meds: Ero Pharm Fast – Ero Pharm Fast

https://pharmau24.shop/# Online drugstore Australia

Awesome blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

buy antibiotics from india: antibiotic without presription – cheapest antibiotics

I really enjoy the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Ero Pharm Fast: Ero Pharm Fast – buying erectile dysfunction pills online

Огонь забежал справа – получил отпор. Moneyman Бесплатная Горячая Линия — О нет, мы выслушаем вас очень внимательно, — серьезно и успокоительно сказал Стравинский, — и в сумасшедшие вас рядить ни в коем случае не позволим.

SpookySwap Staking

Over the counter antibiotics for infection Over the counter antibiotics pills Over the counter antibiotics pills

SpookySwap

http://pharmau24.com/# Online drugstore Australia

Затем, сжав губы, она принялась собирать и расправлять обгоревшие листы. Перевод Паспорта С Нотариальным Заверением На Коломенской На всякий случай спросил, вдруг снова можно своим отцом похвастать, но сразу пожалел об этом.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

— Но ничего не услышите, пока не сядете к столу и не выпьете вина, — любезно ответил Пилат и указал на другое ложе. Сайты Для Знакомства И Секса В Казахстане У Русаны – девятьсот восьмидесятая проба! По микроэлементам, из Мексики.

PharmAu24: Medications online Australia – Licensed online pharmacy AU

Например, совсем малявкой, когда плавать ещё не умел, он бродил по мелководью и оступился в глубокую яму – уж кто знает, откуда такая взялась на пляже? Вода сомкнулась над головой, и время тотчас остановилось. Сайты Секс Знакомства Киев Гера покачала головой, глядя на героя: – Так ты долго не проживешь, глупыш.

– Какое? Сокровищница? – Да нет же, удрать через которое! – Тимур возмутился непонятливостью провидения и подробно объяснил ситуацию. Займ Деньги Народу Мальчишки принялись решать вопрос со своими постелями, что оказалось делом трудным.

SpookySwap

Ero Pharm Fast Ero Pharm Fast erection pills online

Зачем ты себя мучаешь, нося их? Выслушав долгое и путаное объяснение, она легонько взяла голову девочки в руки, велела смотреть в глаза. Нотариальный Перевод Паспорта Печатники Осторожно, чтобы не согнуть, Славка подталкивал засов в ту сторону, где сопротивление казалось больше, а три оставшиеся у друзей руки потихоньку толкали щит вверх и опускали вниз.

Online drugstore Australia: Discount pharmacy Australia – Online medication store Australia

Да, нет сомнений, это она, опять она, непобедимая, ужасная болезнь… гемикрания, при которой болит полголовы… от нее нет средств, нет никакого спасения… попробую не двигать головой…» На мозаичном полу у фонтана уже было приготовлено кресло, и прокуратор, не глядя ни на кого, сел в него и протянул руку в сторону. Секс Знакомства С Женщинами Старше 50 Русана сменила сари – обмоталась в ослепительно синий шёлковый лоскут.

I really like and appreciate your article.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Но удивительнее всего были двое спутников черного мага: длинный клетчатый в треснувшем пенсне и черный жирный кот, который, войдя в уборную на задних лапах, совершенно непринужденно сел на диван, щурясь на оголенные гримировальные лампионы. Займ На Карту Мфо Деньга Дама от этого отказывалась, говоря: «Нет, нет, меня не будет дома!» — а Степа упорно настаивал на своем: «А я вот возьму да и приду!» Ни какая это была дама, ни который сейчас час, ни какое число, ни какого месяца — Степа решительно не знал и, что хуже всего, не мог понять, где он находится.

Из камина выбежал полуистлевший небольшой гроб, крышка его отскочила, и из него вывалился другой прах. My Moneyman Не верю! Лучше, чем в очках! Это чудо! Не может быть! Гера, спасибо вам! Дылда соскочила с лавки, бросилась обнимать старушку, едва не сбив ту на пол.

I am so grateful for your blog.Much thanks again. Want more.

I really like and appreciate your blog post. Much obliged.

Very informative blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Medyum Haluk hoca

Say, you got a nice blog post.Much thanks again.

Very neat blog post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

Wow, great blog.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Awesome blog.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

Thank you ever so for you blog post.Really thank you! Awesome.

I think this is a real great blog article.Really thank you! Awesome.

Great article post.

Im thankful for the blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

SpookySwap

Very informative blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Multichain Trading

Multichain

Multichain Crypto

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

I think this is a real great article.Much thanks again. Great.

Great, thanks for sharing this blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

betpuan güncel giriş adresi <a href="betpuan“>tıkla gir

This is such a great resource that you are providing and you give it away for free.

Great blog.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

Thank you ever so for you article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

I really enjoy the blog.Thanks Again. Great.

Fantastic post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Now I am going to do my breakfast, once having my breakfast coming over again to read further news.

Fraxswap Staking

RenBridge

Im grateful for the blog post. Want more.

We stumbled over here by a different web page and thought

I should check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you.

Look forward to looking into your web page again.

I truly appreciate this article post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright violation?

My site has a lot of completely unique content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it seems a lot

of it is popping it up all over the internet without

my agreement. Do you know any solutions to help prevent content from being stolen?

I’d genuinely appreciate it.

Top platform in Poland.

From my expertise, great site.

Wow, great blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

Highly trusted crypto exchange.

This is one awesome article.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website

yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you?

Plz respond as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to find

out where u got this from. many thanks

Thanks for some other fantastic post. Where else may just

anyone get that kind of info in such an ideal

approach of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I am at the search for such information.

You are a very smart individual!

From my experience, this crypto site is top-tier.

Expert-approved crypto exchange.

Major thankies for the post.Much thanks again. Really Great.

Say, you got a nice blog.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Matcha Swap

MultiChain

MultiChain

Major thankies for the blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it.

Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate?

My brother suggested I may like this blog. He used to

be totally right. This put up truly made my day. You cann’t consider simply

how a lot time I had spent for this info! Thank you!

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my

own weblog and was curious what all is required to get set up?

I’m assuming having a blog like yours would cost

a pretty penny? I’m not very web savvy so I’m not 100% positive.

Any tips or advice would be greatly appreciated. Many thanks

Very good blog article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

Im obliged for the article.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Really informative blog.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Awesome blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere?