Dust to Data: How Timbuktu’s Secret Libraries Escaped War and Went Digital

Hook: Fragile Pages That Outlived Empires

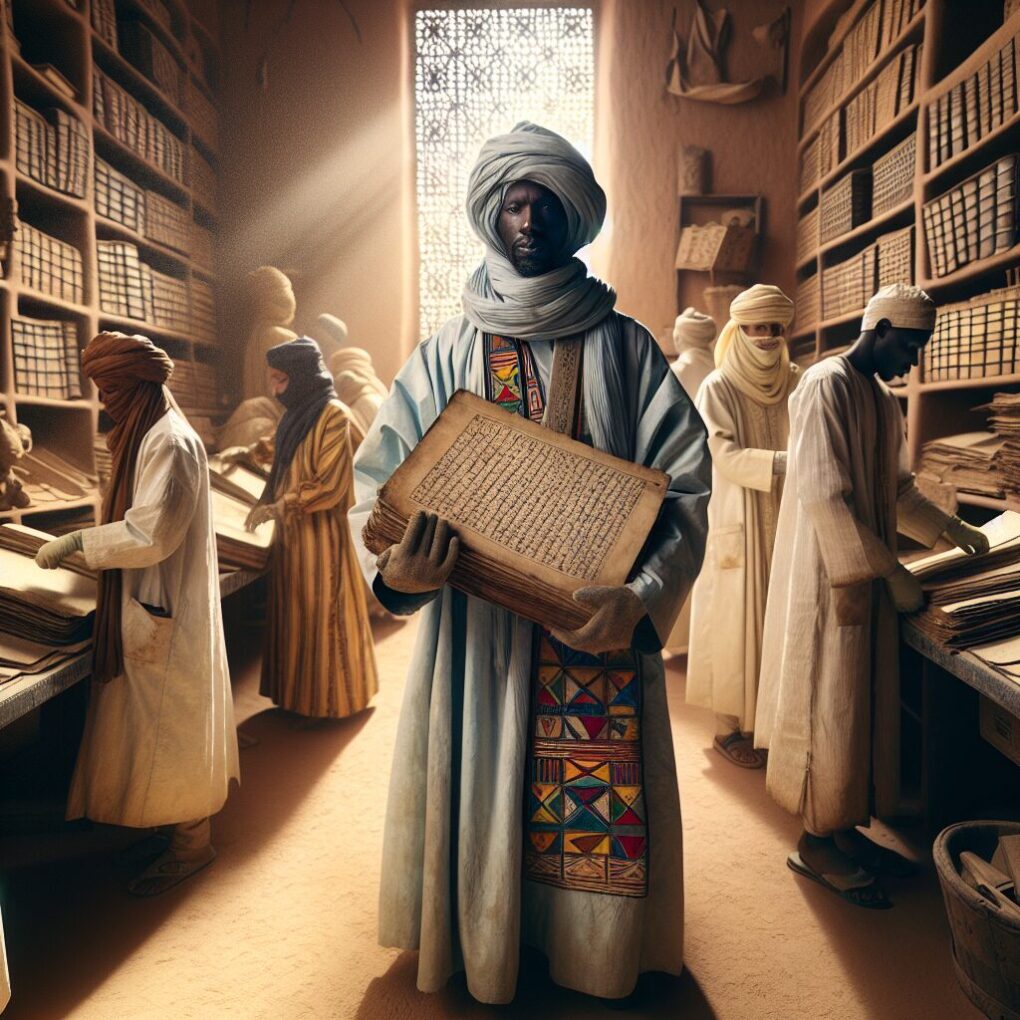

In a city ringed by Sahara and legend, thin folios the color of desert light have survived salt caravans, caliphates, drought, smugglers, and the soft abrasion of human thumbs. Timbuktu’s manuscripts, written in Arabic and Ajami on rag paper and gazelle skin, do not sit on the world’s grand shelves. They lie close to the body of the city, in chests and trunks, inside family libraries that measure time not in years but in copyist hands. These pages have outlived empires. In 2012, when war arrived, they learned to move.

If you came here expecting our usual deep dives into the body and its care, think of this as kin. The same nervous system that remembers touch and scent also remembers words and wisdom. Today, the subject is cultural health, the immune system of memory. It has arteries, risks, and a pulse.

The Night Moves: When Families Became a Network

In spring 2012, as militants took over Timbuktu, scholars, guards, drivers, and cousins built a community network that moved hundreds of thousands of manuscripts out of harm’s way. The work did not announce itself. Boxes were ordinary. Boats were not marked. Conversations were short. The city’s custodial families, who had protected private libraries for generations, read the weather of war the way Sahelian herders read a sand-charged wind, and they acted.

Led by librarians such as Abdel Kader Haidara and the NGO he helped create, SAVAMA-DCI, the network purchased trunks and petty-cash notebooks, hired donkeys and beat-up sedans, and built a schedule that looked like chaos but worked like a heartbeat. Pages that once crossed the Sahara on the backs of camels now rode in old Peugeots to the Niger, then slipped by pirogue to Bamako. Teenagers carried crates at night, then typed text messages by day. Checkpoints were negotiated with patience, tea, and the instinctive calculus of risk that Sahelian traders have honed for centuries.

There are numbers for this, but the human picture is sharper. Imagine a mother in her courtyard rubbing shea butter into a cracked leather binding to soften it for the journey. Picture a librarian weighing a bundle in his hands, feeling the shift of pages like a small animal. Downriver, a driver idles with headlights off, listening to the calls over the water. Across the network, thousands of such gestures turned anxiety into logistics.

By early 2013, as flames rose in a government library and a few priceless volumes were lost, it became clear that the rescue had worked. The overwhelming majority of manuscripts, many reckoned at more than 300,000, had reached secure locations in Bamako and elsewhere in southern Mali. The quiet choreography of a city’s memory had outmaneuvered war.

Inside the Lab: What Conservation Looks Like in Mali Today

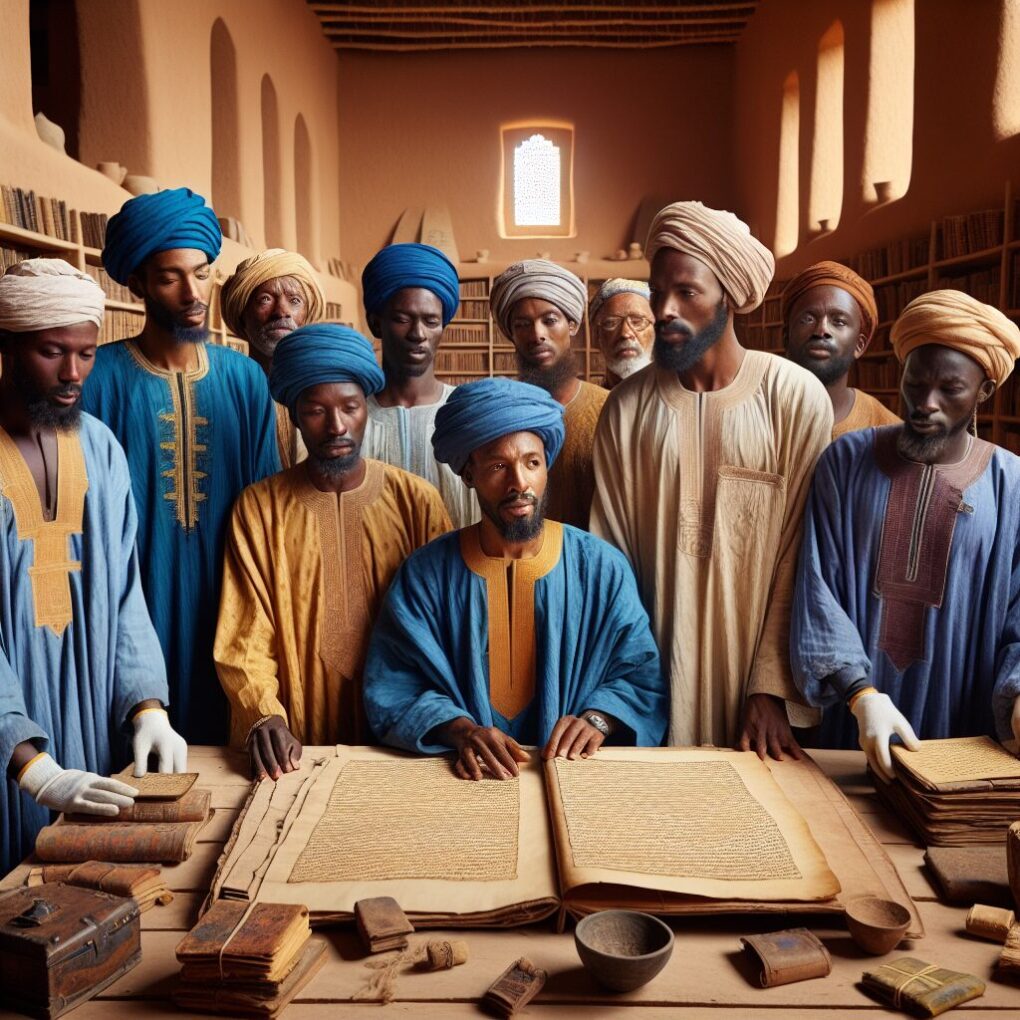

Escape is dramatic. Preservation is the opposite, patient and exact. In Bamako, conservation labs smell of leather, dust, tea, and wheat paste. Restorers work under daylight-balanced lamps, sleeves rolled up, fingertips clean but never gloved when touch matters. These manuscripts were made by hand and read by skin, so conservators let skin inform the work.

A page arrives and rests. Dust is lifted with a soft hake brush or micro vacuum, the motion slow, the wrist loose. If insects have chewed, conservators carry out anoxic treatments, using sealed enclosures with oxygen scavengers to suffocate larvae, since fumigation can be dangerous for both paper and people in small labs.

Humidity is the enemy in the Sahel’s hot season, dryness the enemy in Harmattan months. Conservators stabilize sheets with breathable enclosures and acid-free folders, then mend tears with Japanese kozo tissue and wheat starch paste, a bond that remains reversible. Iron gall ink, common in Saharan manuscripts, can corrode paper. Where resources allow, conservators gently neutralize acidity with buffered solutions or sprays, and sometimes consolidate fragile ink with careful, minimal interventions. Full aqueous de-acidification is rare, since inks may migrate. Every decision is calibrated to do the least harm and to respect the manuscript as a historical object, not only a text.

Bindings receive their own care. Leather covers are cleaned and fed, often with locally appropriate dressings that do not darken or clog pores. Sewing is reinforced where needed, never over-tight. After triage, folios settle into custom boxes cut from archival board. On shelves, small humidity indicators sit like watchful birds.

Resource constraints shape practice. Power flickers, so labs use solar panels where they can. Air conditioning is expensive, so rooms rely on cross-ventilation and thick walls that mimic Sahelian architecture. Training is ongoing and local, a slow accumulation of skill, because expertise that can leave can be lost. In this work, a steady hand is a form of sovereignty.

From Desert Script to Global Cloud: How Digitization Protects Sahelian Scholarship

To keep a manuscript safe, you limit its touch. To keep a manuscript alive, you make it legible. Digitization holds these truths together.

In Mali, digitization stations look like modest photo studios. A copy stand. A high-resolution camera fixed to a column. Lights at 45 degrees, diffused to avoid glare on burnished paper. A color target and ruler for every session, so future users can calibrate and trust. Conservators turn pages with a bone folder and a breath. Photographers shoot in RAW. Files are backed up on local drives, then synced to cloud servers when bandwidth and power allow.

Metadata is the skeleton for discovery. Catalogers record titles, authors, scribes, dates, script types, marginalia, seals, and ownership notes. Many notes are in Arabic, many more in French and English for global access. Where texts are in Ajami, African languages written in Arabic script, catalogers collaborate with linguists to make the work visible to communities who can read it in both traditions.

Partnerships make this possible. The Hill Museum and Manuscript Library has supported digitization and cataloging for years. The British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme helped fund equipment and training. The Ahmed Baba Institute, SAVAMA-DCI, and allied family libraries coordinate logistics and host digitization teams. Google’s Mali Magic portal brought selections to a broad public, pairing manuscripts with music, monuments, and recorded voices so the collection speaks beyond the page.

The result is a paradox worth celebrating. A book that settled for centuries in a trunk in a courtyard now appears on a phone in São Paulo or Nairobi. A student in Bamako can read it without permission from Paris. A researcher in Accra can trace a legal formula across centuries and cities, then send a citation back to the family that kept the text alive. Access becomes reciprocity.

What the Pages Reveal: A Vast, Rigorous African Written Tradition

The stereotype that Africa’s intellectual history is only oral collapses when you read these pages. The Timbuktu libraries hold the everyday and the sublime.

- Astronomy, in treatises that chart lunar stations, eclipse predictions, and prayer times, connecting celestial cycles to social life.

- Law, in layered commentaries that travel from North African Maliki jurisprudence to local judgments about trade, inheritance, and marriage.

- Medicine, in recipes that combine Qur’anic healing traditions with pharmacopoeias of desert and river plants. There are dosages, cautions, and practical wisdom, the kind of applied science that keeps families alive.

- Poetry, devotional and secular, that parses desire, grief, and ethics in meters that mirror the cadence of Sahelian music.

- Trade and diplomacy, in letters that stitch Timbuktu to cities from Walata to Cairo, and to Mediterranean ports. The archives are thick with receipts, valuations, and strategies. They read like spreadsheets, but with more beauty at the margins.

Scholars have shown that these libraries are not anomalies. They sit in an arc of literacy that runs across the Sahel, in places like Djenné, Chinguetti, and Agadez, and they connect to Senegambian and Hausa Ajami traditions. This is a written Africa, vigorous and pragmatic, arguing with itself in footnotes and glosses, both rooted and cosmopolitan.

The Funding Puzzle: Grants, Stewardship, and Why Long-Term Support Still Matters

Rescue operations capture attention. Conservation and cataloging need time and quiet money. The work in Mali has drawn support from private foundations and public programs, from institutions in the region and abroad. Grants have paid for boxes, cameras, solar panels, and stipends. Training programs have built local capacity, so a broken binding can be mended in Bamako, not flown to Europe.

Yet insecurity in northern Mali persists, and climate stress in the Sahel grows. Floods in Bamako, extreme heat, and volatile electricity compound risk. Libraries cannot plan on a three-month grant cycle. They need multi-year commitments that cover salaries, maintenance, insurance, and emergency planning. They need the slow capital of trust.

Local stewardship is the anchor. Family libraries have always carried more than pages. They hold social legitimacy in their neighborhoods. They teach by presence. A grant that strengthens a family library strengthens a street and a city. When donors treat custodians as full partners, with decision-making power and shared authorship, projects work better and last longer.

Pride and Protection: Frontline Defenders of African Memory

In every story of rescue, there is pride that is not loud but steady. Custodial families do not romanticize their task. They name it. These are inheritances, and inheritances demand care. The work implicates the body. You lift. You breathe dust. You negotiate when negotiation is dangerous. You risk without posturing.

Consider Aïcha, a composite of several women conservators in Bamako. She grew up seeing her grandfather’s books, felt their status and their fragility. During the 2012 evacuations she hosted crates in her home, then learned to mend tears and to build boxes. She is now one of the people teaching others. Her pride is technical and civic. When she explains a repair, you hear both the science and the love.

Archivists and librarians in Mali, men and women, operate at a crossing where cultural memory, public service, and personal courage meet. They are the frontline defenders of African memory because they are also neighbors and kin. That proximity is power. It is what allowed the manuscripts to move at the speed of trust.

The Road Ahead: Training, Open Access, and Climate-Resilient Archives

The manuscripts have exited the most acute danger. Now they face the long challenges that make or break archives.

- Build more conservators. Expand training programs in Mali and the wider Sahel. Support apprenticeships that mix global best practices with local materials and climate realities. Invest in instructors and in the careers of the students they mentor.

- Expand open access, with care. Digitize intelligently, prioritize unique and fragile items, and publish in platforms that respect community ownership and context. Pair images with translations and commentaries from Sahelian scholars. Metadata should be multilingual, and search should serve both specialists and young readers looking for their first connection.

- Design for climate. Upgrade storage using passive cooling inspired by Sahelian architecture, with thick earthen walls, ventilated attics, and shaded courtyards. Add solar power and battery backups. Install low-tech humidity buffers and early warning sensors that text staff when conditions change.

- Plan for disaster. Every library needs a simple, rehearsed plan for flood, fire, and conflict. Fire-resistant cabinets, water-resistant crates, evacuation routes, contacts, insurance, and a chain of custody for digital files. Practice matters.

- Strengthen governance. Transparent budgets, clear custodianship agreements, and community oversight keep the work honest and defensible. Include women and young professionals in decision-making, not only in labor.

How This Differs From Our Usual Beat

We often talk about the individual body, the quiet choreography of hormones, sleep, food, and desire. Today’s story is about a cultural body and its health. The skills are analogous, precision and patience, and the stakes are intimate in a different way. When a city keeps its memory, it keeps its self-respect. The lesson carries back into the personal. Protect what feeds you. Share what keeps others strong.

What You Can Do, Wherever You Are

Hold two ideas at once, that African knowledge has always been written and argued, and that manuscripts require continuous care. Visit digital portals, read a page, cite a Sahelian scholar. If you are in a position to help, support the institutions on the ground that make conservation and access possible. If you teach, bring a manuscript into your classroom with attribution and context. If you build technology, partner with libraries to improve open, resilient platforms.

The pages of Timbuktu survived because people treated them as living. They still are. What will you do with the breath they have saved for you?

References and Further Reading

- SAVAMA-DCI, official communications on the evacuation and preservation of manuscripts in Mali. https://www.savama-dci.org

- Hammer J. The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, and Their Race to Save the World’s Most Precious Manuscripts. Simon & Schuster, 2016.

- Jeppie S, Diagne S B, editors. The Meanings of Timbuktu. HSRC Press, 2008.

- UNESCO, Timbuktu and its manuscripts, reports on heritage protection and the 2012–2013 crisis. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/119/

- British Library, Endangered Archives Programme, projects in Mali and West Africa. https://eap.bl.uk

- Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, HMML Reading Room and preservation initiatives in Mali. https://www.hmml.org

- Google Arts and Culture, Mali Magic, digital access to Malian cultural heritage, including manuscripts. https://artsandculture.google.com/project/mali-magic

- Chartier A C et al., Guidance on the conservation of Islamic manuscripts, including treatments for iron gall ink and storage best practices, various publications by the Islamic Manuscript Association. https://www.islamicmanuscript.org

- University of Cape Town, Tombouctou Manuscripts Project, research on manuscript cultures in the Sahel. https://www.tombouctoumanuscripts.org

Note on numbers and claims: Evacuation figures and partner roles reflect widely reported estimates and institutional summaries, which may vary by source. Where exact counts are contested, this article opts for conservative language, hundreds of thousands of manuscripts and folios, consistent with NGO and media reports.

Pera Museum tour Perfect for a half-day or full-day sightseeing. https://repurtech.com/?p=352669

Dent Global İstanbul ortodontri, acil diş çekimi, 20 lik diş çekimi, diş estetik

Perpa Kameram | Güvenlik Kameraları güvenlik kamerası, gizli kamera, kamera sistemleri, güvenlik sistemleri

En İyi Güvenlik | Güvenlik Kameraları güvenlik kamerası, gizli kamera, kamera sistemleri, güvenlik sistemleri

Excellent blog here Also your website loads up very fast What web host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Good write-up, I am normal visitor of one¦s site, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

You have observed very interesting details! ps decent web site. “Ask me no questions, and I’ll tell you no fibs.” by Oliver Goldsmith.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to your weblog when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

I’ll right away grasp your rss feed as I can’t to find your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please allow me recognise so that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

There are some attention-grabbing cut-off dates on this article but I don’t know if I see all of them center to heart. There’s some validity but I will take maintain opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like more! Added to FeedBurner as properly

Your blog is a true hidden gem on the internet. Your thoughtful analysis and engaging writing style set you apart from the crowd. Keep up the excellent work!

Good day! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my old room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Fairly certain he will have a good read. Many thanks for sharing!

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of information. I’m happy that you simply shared this useful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

I’m extremely impressed with your writing abilities as well as with the layout for your blog. Is this a paid subject matter or did you modify it your self? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it is uncommon to see a nice blog like this one these days..

I think this site has some rattling great information for everyone :D. “Laughter is the sun that drives winter from the human face.” by Victor Hugo.

**mindvault**

mindvault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you’ve put in writing this blog. I am hoping the same high-grade website post from you in the upcoming as well. In fact your creative writing skills has inspired me to get my own website now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a good example of it.

**glpro**

glpro is a natural dietary supplement designed to promote balanced blood sugar levels and curb sugar cravings.

**sugarmute**

sugarmute is a science-guided nutritional supplement created to help maintain balanced blood sugar while supporting steady energy and mental clarity.

**vitta burn**

vitta burn is a liquid dietary supplement formulated to support healthy weight reduction by increasing metabolic rate, reducing hunger, and promoting fat loss.

**synaptigen**

synaptigen is a next-generation brain support supplement that blends natural nootropics, adaptogens

**glucore**

glucore is a nutritional supplement that is given to patients daily to assist in maintaining healthy blood sugar and metabolic rates.

**prodentim**

prodentim an advanced probiotic formulation designed to support exceptional oral hygiene while fortifying teeth and gums.

**nitric boost**

nitric boost is a dietary formula crafted to enhance vitality and promote overall well-being.

**wildgut**

wildgutis a precision-crafted nutritional blend designed to nurture your dog’s digestive tract.

**sleep lean**

sleeplean is a US-trusted, naturally focused nighttime support formula that helps your body burn fat while you rest.

**mitolyn**

mitolyn a nature-inspired supplement crafted to elevate metabolic activity and support sustainable weight management.

**yu sleep**

yusleep is a gentle, nano-enhanced nightly blend designed to help you drift off quickly, stay asleep longer, and wake feeling clear.

**zencortex**

zencortex contains only the natural ingredients that are effective in supporting incredible hearing naturally.

**breathe**

breathe is a plant-powered tincture crafted to promote lung performance and enhance your breathing quality.

**prostadine**

prostadine is a next-generation prostate support formula designed to help maintain, restore, and enhance optimal male prostate performance.

**pineal xt**

pinealxt is a revolutionary supplement that promotes proper pineal gland function and energy levels to support healthy body function.

**energeia**

energeia is the first and only recipe that targets the root cause of stubborn belly fat and Deadly visceral fat.

**prostabliss**

prostabliss is a carefully developed dietary formula aimed at nurturing prostate vitality and improving urinary comfort.

**boostaro**

boostaro is a specially crafted dietary supplement for men who want to elevate their overall health and vitality.

**potent stream**

potent stream is engineered to promote prostate well-being by counteracting the residue that can build up from hard-water minerals within the urinary tract.

**hepato burn**

hepato burn is a premium nutritional formula designed to enhance liver function, boost metabolism, and support natural fat breakdown.

**hepato burn**

hepato burn is a potent, plant-based formula created to promote optimal liver performance and naturally stimulate fat-burning mechanisms.

**flow force max**

flow force max delivers a forward-thinking, plant-focused way to support prostate health—while also helping maintain everyday energy, libido, and overall vitality.

**neurogenica**

neurogenica is a dietary supplement formulated to support nerve health and ease discomfort associated with neuropathy.

**cellufend**

cellufend is a natural supplement developed to support balanced blood sugar levels through a blend of botanical extracts and essential nutrients.

**prodentim**

prodentim is a forward-thinking oral wellness blend crafted to nurture and maintain a balanced mouth microbiome.

**revitag**

revitag is a daily skin-support formula created to promote a healthy complexion and visibly diminish the appearance of skin tags.

Somebody essentially help to make significantly articles Id state This is the first time I frequented your web page and up to now I surprised with the research you made to make this actual post incredible Fantastic job

Great article, thank you for sharing these insights! I’ve tested many methods for building backlinks, and what really worked for me was using AI-powered automation. With us, we can scale link building in a safe and efficient way. It’s amazing to see how much time this saves compared to manual outreach. https://seoexpertebamberg.de/

**memory lift**

memory lift is an innovative dietary formula designed to naturally nurture brain wellness and sharpen cognitive performance.

This is a great article, i am simply a fun, keep up the good work, just finish reading from https://websiteerstellenlassenbamberg.de// and their work is fantastic. i will be checking your content again if you make next update or post. Thank you

My brother recommended I would possibly like this web site. He used to be entirely right. This submit actually made my day. You cann’t imagine simply how much time I had spent for this information! Thank you!

**hepatoburn**

hepatoburn is a potent, plant-based formula created to promote optimal liver performance and naturally stimulate fat-burning mechanisms.

Your passion for your subject matter shines through in every post. It’s clear that you genuinely care about sharing knowledge and making a positive impact on your readers. Kudos to you!

Hey, you used to write wonderful, but the last several posts have been kinda boring?K I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a bit out of track! come on!

I’m still learning from you, as I’m trying to reach my goals. I definitely enjoy reading all that is posted on your website.Keep the aarticles coming. I liked it!

you are in reality a just right webmaster. The web site loading speed is incredible. It seems that you are doing any distinctive trick. In addition, The contents are masterpiece. you have done a excellent job on this subject!

Your blog is a breath of fresh air in the often stagnant world of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with us.

Great post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed! Extremely useful information specially the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this particular information for a very long time. Thank you and best of luck.

Your blog is a beacon of light in the often murky waters of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Keep up the amazing work!

Thank you for another wonderful post. The place else may just anybody get that type of info in such a perfect means of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at the look for such information.

Excellent breakdown, I like it, nice article. I completely agree with the challenges you described. For our projects we started using Listandsell.us and experts for our service, Americas top classified growing site, well can i ask zou a question regarding zour article?

obviously like your website but you need to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth on the other hand I will definitely come again again.

Way cool, some valid points! I appreciate you making this article available, the rest of the site is also high quality. Have a fun.

Some times its a pain in the ass to read what blog owners wrote but this site is very user genial! .

Interesting blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your design. Appreciate it

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great website and I look forward to seeing it develop over time.

I have read a few just right stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you set to make this sort of fantastic informative site.

certainly like your website but you need to take a look at the spelling on quite a few of your posts Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very troublesome to inform the reality nevertheless I will definitely come back again

You can certainly see your skills in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always follow your heart.

I truly enjoy looking at on this web site, it has got fantastic content. “Never fight an inanimate object.” by P. J. O’Rourke.

Hello my loved one I want to say that this post is amazing great written and include almost all significant infos I would like to look extra posts like this

Great ?V I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs as well as related info ended up being truly simple to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, web site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

Hiya! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My web site looks weird when browsing from my iphone4. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to fix this issue. If you have any recommendations, please share. With thanks!

I’ve recently started a website, the info you provide on this web site has helped me tremendously. Thank you for all of your time & work.

This blog is definitely rather handy since I’m at the moment creating an internet floral website – although I am only starting out therefore it’s really fairly small, nothing like this site. Can link to a few of the posts here as they are quite. Thanks much. Zoey Olsen

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

Very well written article. It will be helpful to anyone who usess it, as well as yours truly :). Keep up the good work – can’r wait to read more posts.

great publish, very informative. I ponder why the other experts of this sector don’t notice this. You must continue your writing. I am sure, you’ve a great readers’ base already!

Hey are using WordPress for your blog platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and create my own. Do you require any html coding knowledge to make your own blog? Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Have you ever considered creating an ebook or guest authoring on other blogs? I have a blog based on the same topics you discuss and would really like to have you share some stories/information. I know my readers would appreciate your work. If you are even remotely interested, feel free to shoot me an e mail.

**aqua sculpt**

aquasculpt is a premium fat-burning supplement meticulously formulated to accelerate your metabolism and increase your energy output.

**backbiome**

backbiome is a naturally crafted, research-backed daily supplement formulated to gently relieve back tension and soothe sciatic discomfort.

**boostaro**

boostaro is a specially crafted dietary supplement for men who want to elevate their overall health and vitality.

**aqua sculpt**

aquasculpt is a revolutionary supplement crafted to aid weight management by naturally accelerating metabolism

**hepato burn**

hepatoburn is a high-quality, plant-forward dietary blend created to nourish liver function, encourage a healthy metabolic rhythm, and support the bodys natural fat-processing pathways.

**vivalis**

vivalis is a premium natural formula created to help men feel stronger, more energetic, and more confident every day.

**alpha boost**

alpha boost for men, feeling strong, energized, and confident is closely tied to overall quality of life. However, with age, stress, and daily demands

**nitric boost**

nitric boost is a daily wellness blend formulated to elevate vitality and support overall performance.

**synadentix**

synadentix is a dental health supplement created to nourish and protect your teeth and gums with a targeted combination of natural ingredients

**nervecalm**

nervecalm is a high-quality nutritional supplement crafted to promote nerve wellness, ease chronic discomfort, and boost everyday vitality.

**glycomute**

glycomute is a natural nutritional formula carefully created to nurture healthy blood sugar levels and support overall metabolic performance.

**yu sleep**

yusleep is a gentle, nano-enhanced nightly blend designed to help you drift off quickly, stay asleep longer, and wake feeling clear

**gl pro**

glpro is a natural dietary supplement designed to promote balanced blood sugar levels and curb sugar cravings.

**prodentim**

prodentim is a distinctive oral-care formula that pairs targeted probiotics with plant-based ingredients to encourage strong teeth

**mindvault**

mindvault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+.

**balmorex**

balmorex is an exceptional solution for individuals who suffer from chronic joint pain and muscle aches.

**vitrafoxin**

vitrafoxin is a premium brain enhancement formula crafted with natural ingredients to promote clear thinking, memory retention, and long-lasting mental energy.

**provadent**

provadent is a newly launched oral health supplement that has garnered favorable feedback from both consumers and dental professionals.

**femipro**

femipro is a dietary supplement developed as a natural remedy for women facing bladder control issues and seeking to improve their urinary health.

**glucore**

glucore is a nutritional supplement that is given to patients daily to assist in maintaining healthy blood sugar and metabolic rates.

**sleep lean**

is a US-trusted, naturally focused nighttime support formula that helps your body burn fat while you rest.

**vertiaid**

vertiaid is a high-quality, natural formula created to support stable balance, enhance mental sharpness, and alleviate feelings of dizziness

**tonic greens**

tonic greens is a cutting-edge health blend made with a rich fusion of natural botanicals and superfoods, formulated to boost immune resilience and promote daily vitality.

**prostavive**

prostavive Maintaining prostate health is crucial for mens overall wellness, especially as they grow older.

**sugarmute**

sugarmute is a science-guided nutritional supplement created to help maintain balanced blood sugar while supporting steady energy and mental clarity

**primebiome**

The natural cycle of skin cell renewal plays a vital role in maintaining a healthy and youthful appearance by shedding old cells and generating new ones.

**oradentum**

oradentum is a comprehensive 21-in-1 oral care formula designed to reinforce enamel, support gum vitality, and neutralize bad breath using a fusion of nature-derived, scientifically validated compounds.

Thanks for another informative website. The place else could I get that kind of info written in such a perfect manner? I’ve a project that I am just now running on, and I have been on the look out for such information.

**biodentex**

biodentex is a dentist-endorsed oral wellness blend crafted to help fortify gums, defend enamel, and keep your breath consistently fresh.

I like this weblog very much so much good information.

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

**wildgut**

wildgut is a precision-crafted nutritional blend designed to nurture your dogs digestive tract.

**mitolyn**

mitolyn is a plant-forward blend formulated to awaken metabolic efficiency and support steady, sustainable weight management.

**prostadine**

prostadine concerns can disrupt everyday rhythm with steady discomfort, fueling frustration and a constant hunt for dependable relief.

**ignitra**

ignitra is a premium, plant-based dietary supplement created to support healthy metabolism, weight management, steady energy, and balanced blood sugar as part of an overall wellness routine

**finessa**

Finessa is a natural supplement made to support healthy digestion, improve metabolism, and help you achieve a flatter belly.

**neurosharp**

neurosharp is a next-level brain and cognitive support formula created to help you stay clear-headed, improve recall, and maintain steady mental performance throughout the day.

фен купить дайсон оригинал [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-12.ru/]fen-dn-kupit-12.ru[/url] .

фен купить дайсон оригинал [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-13.ru/]fen-dn-kupit-13.ru[/url] .

купить фен dyson оригинал [url=https://stajler-dsn-1.ru/]купить фен dyson оригинал[/url] .

официальный сайт дайсон стайлер для волос купить цена с насадкам… [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-13.ru/]официальный сайт дайсон стайлер для волос купить цена с насадкам…[/url] .

дайсон официальный сайт стайлер для волос с насадками купить цен… [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-12.ru/]fen-dn-kupit-12.ru[/url] .

купить дайсон в москве оригинал [url=https://stajler-dsn-1.ru/]stajler-dsn-1.ru[/url] .

дайсон стайлер для волос официальный сайт с насадками купить цен… [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-13.ru/]дайсон стайлер для волос официальный сайт с насадками купить цен…[/url] .

дайсон фен купить в москве оригинал [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-12.ru/]дайсон фен купить в москве оригинал[/url] .

цена дайсон стайлер для волос с насадками официальный сайт купит… [url=https://stajler-dsn-1.ru/]цена дайсон стайлер для волос с насадками официальный сайт купит…[/url] .

дайсон стайлер для волос с насадками цена купить официальный сай… [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-13.ru/]дайсон стайлер для волос с насадками цена купить официальный сай…[/url] .

купить фен дайсон официальный сайт [url=https://fen-dn-kupit-12.ru/]купить фен дайсон официальный сайт[/url] .

фен дайсон как отличить оригинал [url=https://stajler-dsn-1.ru/]stajler-dsn-1.ru[/url] .

Woah! I’m really digging the template/theme of this site. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness and visual appearance. I must say you’ve done a very good job with this. Also, the blog loads extremely fast for me on Internet explorer. Superb Blog!

пылесос дайсон absolute купить [url=https://dn-pylesos.ru/]пылесос дайсон absolute купить[/url] .

купить dyson купить [url=https://dn-pylesos.ru/]dn-pylesos.ru[/url] .

пылесос дайсон v15 оригинал [url=https://dn-pylesos.ru/]dn-pylesos.ru[/url] .

пылесос дайсон купить во владимире [url=https://dn-pylesos.ru/]dn-pylesos.ru[/url] .

выпрямитель дайсон купить [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-4.ru/]выпрямитель дайсон купить[/url] .

купить оригинальный дайсон фен выпрямитель [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-4.ru/]vypryamitel-dn-4.ru[/url] .

выпрямитель дайсон airstrait [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-4.ru/]выпрямитель дайсон airstrait[/url] .

Aw, this was a very nice post. In idea I wish to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and actual effort to make an excellent article… but what can I say… I procrastinate alot and in no way seem to get something done.

выпрямитель для волос дайсон москва [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-4.ru/]выпрямитель для волос дайсон москва[/url] .

выпрямитель дайсон [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-kupit-4.ru/]выпрямитель дайсон[/url] .

выпрямитель волос dyson ht01 [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-kupit-4.ru/]выпрямитель волос dyson ht01[/url] .

выпрямитель для волос дайсон купить [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-kupit-4.ru/]выпрямитель для волос дайсон купить[/url] .

выпрямитель дайсон купить в екатеринбурге [url=https://vypryamitel-dn-kupit-4.ru/]выпрямитель дайсон купить в екатеринбурге[/url] .

Some genuinely interesting information, well written and generally user genial.

You really make it appear so easy together with your presentation however I to find this topic to be really one thing which I believe I’d by no means understand. It sort of feels too complicated and very huge for me. I am taking a look ahead on your subsequent publish, I¦ll attempt to get the hang of it!

выпрямитель dyson airstrait ht01 купить минск [url=https://vypryamitel-dsn-kupit-4.ru/]vypryamitel-dsn-kupit-4.ru[/url] .

купить выпрямитель волос dyson [url=https://vypryamitel-dsn-kupit-4.ru/]купить выпрямитель волос dyson[/url] .

многоуровневый линкбилдинг [url=https://seo-kejsy7.ru/]seo-kejsy7.ru[/url] .

школы дистанционного обучения [url=https://shkola-onlajn13.ru/]shkola-onlajn13.ru[/url] .

I dugg some of you post as I thought they were handy very beneficial

выпрямитель dyson corrale купить [url=https://vypryamitel-dsn-kupit-4.ru/]выпрямитель dyson corrale купить[/url] .

ахревс [url=https://seo-kejsy7.ru/]seo-kejsy7.ru[/url] .

ломоносов онлайн школа [url=https://shkola-onlajn13.ru/]shkola-onlajn13.ru[/url] .

I used to be suggested this website by means of my cousin. I am no longer certain whether or not this publish is written via him as nobody else recognize such specified about my trouble. You’re amazing! Thank you!

выпрямитель dyson ht01 [url=https://vypryamitel-dsn-kupit-4.ru/]выпрямитель dyson ht01[/url] .

реклама наркологической клиники [url=https://seo-kejsy7.ru/]реклама наркологической клиники[/url] .

лбс это [url=https://shkola-onlajn13.ru/]shkola-onlajn13.ru[/url] .

закупка ссылок в гугл заказать услугу агентство [url=https://seo-kejsy7.ru/]seo-kejsy7.ru[/url] .

онлайн-школа с аттестатом бесплатно [url=https://shkola-onlajn13.ru/]shkola-onlajn13.ru[/url] .

**herpafend**

herpafend is a natural wellness formula developed for individuals experiencing symptoms related to the herpes simplex virus.

To be honest, I wanted to buy Doxycycline without waiting and came across this amazing site. They let you buy antibiotics without a prescription legally. If you have a toothache, check this shop. Express delivery available. More info: this site. Highly recommended.

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital to assert that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Anyway I’ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

Actually, I had to find Doxycycline quickly and stumbled upon a reliable pharmacy. They let you buy antibiotics without a prescription securely. In case of a toothache, I recommend this site. Overnight shipping guaranteed. Link: this site. Good luck.

**neuro sharp**

neurosharp is a next-level brain and cognitive support formula created to help you stay clear-headed, improve recall, and maintain steady mental performance throughout the day

**vivalis**

vivalis is a premium, plant-forward supplement created to help support mens daily drive, self-assurance, and steady energy.

**aqua sculpt**

aquasculpt is a premium metabolism-support supplement thoughtfully developed to help promote efficient fat utilization and steadier daily energy.

**alpha boost**

For men, feeling strong, energized, and confident is closely tied to overall quality of life. However, with age, stress, and daily demands

Actually, I was looking for anti-parasitic meds pills and discovered this reliable site. They provide 3mg, 6mg & 12mg tablets delivered fast. For treating lice safely, this is the best place: https://ivermectinexpress.xyz/#. Cheers

**prostabliss**

prostabliss is a carefully developed dietary formula aimed at nurturing prostate vitality and improving urinary comfort.

**zencortex**

zencortex Research’s contains only the natural ingredients that are effective in supporting incredible hearing naturally.

**ignitra**

ignitra is a thoughtfully formulated, plant-based dietary supplement designed to support metabolic health, balanced weight management, steady daily energy, and healthy blood sugar levels as part of a holistic wellness approach.

букмекерская контора мелбет официальный сайт [url=https://www.rusfusion.ru]букмекерская контора мелбет официальный сайт[/url] .

курсовые под заказ [url=https://kupit-kursovuyu-43.ru/]курсовые под заказ[/url] .

**back biome**

back biome is a naturally crafted, research-backed daily supplement formulated to gently relieve back tension and soothe sciatic discomfort.

**provadent**

provadent is a recently introduced oral wellness supplement thats been receiving positive attention from everyday users as well as dental experts.

**mitolyn**

mitolyn is a carefully developed, plant-based formula created to help support metabolic efficiency and encourage healthy, lasting weight management.

**gl pro**

gl pro is a natural dietary supplement formulated to help maintain steady, healthy blood sugar levels while easing persistent sugar cravings. Instead of relying on typical drug-like ingredient

где можно заказать курсовую работу [url=https://kupit-kursovuyu-43.ru/]где можно заказать курсовую работу[/url] .

melbet betting company [url=https://rusfusion.ru]melbet betting company[/url] .

**gluco tonic**

gluco tonic is an expertly formulated dietary supplement designed to help maintain balanced blood sugar levels naturally.

**nitric boost ultra**

nitric is a daily wellness formula designed to enhance vitality and help support all-around performance.

помощь студентам контрольные [url=https://kupit-kursovuyu-43.ru/]kupit-kursovuyu-43.ru[/url] .

melbet букмекерская контора [url=www.rusfusion.ru/]melbet букмекерская контора[/url] .

срочно курсовая работа [url=https://kupit-kursovuyu-43.ru/]kupit-kursovuyu-43.ru[/url] .

букмекерская контора мелбет сайт [url=rusfusion.ru]букмекерская контора мелбет сайт[/url] .

**finessa**

finessa is a natural supplement made to support healthy digestion, improve metabolism, and help you achieve a flatter belly. Its unique blend of probiotics and nutrients works together to keep your gut balanced and your body energized

**nervecalm**

nervecalm is a high-quality nutritional supplement crafted to promote nerve wellness, ease chronic discomfort, and boost everyday vitality.

**purdentix**

purdentix is a dietary supplement formulated to support oral health by blending probiotics and natural ingredients.

**biodentex**

biodentex is an advanced oral wellness supplement made for anyone who wants firmer-feeling teeth, calmer gums, and naturally cleaner breath over timewithout relying solely on toothpaste, mouthwash, or strong chemical rinses.

Selam, ödeme yapan casino siteleri bulmak istiyorsanız, bu siteye mutlaka göz atın. Lisanslı firmaları ve fırsatları sizin için listeledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: https://cassiteleri.us.org/# casino siteleri 2026 bol şanslar.

Merhaba arkadaşlar, ödeme yapan casino siteleri bulmak istiyorsanız, hazırladığımız listeye kesinlikle göz atın. Lisanslı firmaları ve bonusları sizin için inceledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: [url=https://cassiteleri.us.org/#]kaçak bahis siteleri[/url] bol şanslar.

п»їHalo Slotter, cari situs slot yang hoki? Coba main di Bonaslot. RTP Live tertinggi hari ini dan terbukti membayar. Deposit bisa pakai Pulsa tanpa potongan. Daftar sekarang: п»їBonaslot salam jackpot.

Bu sene popГјler olan casino siteleri hangileri? CevabД± platformumuzda mevcuttur. Deneme bonusu veren siteleri ve gГјncel giriЕџ linklerini paylaЕџД±yoruz. Hemen tД±klayД±n п»ї[url=https://cassiteleri.us.org/#]canlД± casino siteleri[/url] kazanmaya baЕџlayД±n.

Bocoran slot gacor malam ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Website ini anti rungkad dan aman. Promo menarik menanti anda. Kunjungi: [url=https://bonaslotind.us.com/#]klik disini[/url] dan menangkan.

Bocoran slot gacor hari ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Website ini anti rungkad dan aman. Promo menarik menanti anda. Kunjungi: п»ї[url=https://bonaslotind.us.com/#]slot gacor hari ini[/url] dan menangkan.

Pin-Up AZ ölkəmizdə ən populyar kazino saytıdır. Burada minlərlə oyun və canlı dilerlər var. Qazancı kartınıza anında köçürürlər. Mobil tətbiqi də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Rəsmi sayt https://pinupaz.jp.net/# Pin Up kazino baxın.

Salamlar, əgər siz etibarlı kazino axtarırsınızsa, mütləq Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Ən yaxşı slotlar və sürətli ödənişlər burada mövcuddur. Qeydiyyatdan keçin və bonus qazanın. Oynamaq üçün link: https://pinupaz.jp.net/# sayta keçid uğurlar hər kəsə!

Canlı casino oynamak isteyenler için rehber niteliğinde bir site: listeyi gör Nerede oynanır diye düşünmeyin. Onaylı casino siteleri listesi ile rahatça oynayın. Tüm liste linkte.

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, bura baxa bilərsiniz. İşlək link vasitəsilə hesabınıza girin və qazanmağa başlayın. Pulsuz fırlanmalar sizi gözləyir. Keçid: Pin Up kazino uğurlar.

Bu sene en çok kazandıran casino siteleri hangileri? Cevabı platformumuzda mevcuttur. Deneme bonusu veren siteleri ve güncel giriş linklerini paylaşıyoruz. İncelemek için cassiteleri.us.org fırsatı kaçırmayın.

Selamlar, güvenilir casino siteleri arıyorsanız, bu siteye kesinlikle göz atın. Lisanslı firmaları ve bonusları sizin için inceledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: https://cassiteleri.us.org/# cassiteleri.us.org bol şanslar.

Yeni Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, doğru yerdesiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə qeydiyyat olun və qazanmağa başlayın. Pulsuz fırlanmalar sizi gözləyir. Keçid: https://pinupaz.jp.net/# pinupaz.jp.net hamıya bol şans.

seo аудит веб сайта [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve115.ru/]seo аудит веб сайта[/url] .

Selam, sağlam casino siteleri bulmak istiyorsanız, hazırladığımız listeye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve bonusları sizin için listeledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: buraya tıkla bol şanslar.

сделать аудит сайта цена [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve119.ru/]сделать аудит сайта цена[/url] .

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, bura baxa bilərsiniz. İşlək link vasitəsilə qeydiyyat olun və oynamağa başlayın. Xoş gəldin bonusu sizi gözləyir. Keçid: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]Pin Up online[/url] qazancınız bol olsun.

Salam Gacor, cari situs slot yang gacor? Coba main di Bonaslot. Winrate tertinggi hari ini dan pasti bayar. Deposit bisa pakai OVO tanpa potongan. Login disini: https://bonaslotind.us.com/# bonaslotind.us.com salam jackpot.

Bonaslot adalah agen judi slot online terpercaya di Indonesia. Ribuan member sudah merasakan Maxwin sensasional disini. Proses depo WD super cepat hanya hitungan menit. Link alternatif п»ї[url=https://bonaslotind.us.com/#]slot gacor hari ini[/url] gas sekarang bosku.

Halo Bosku, lagi nyari situs slot yang mudah menang? Rekomendasi kami adalah Bonaslot. RTP Live tertinggi hari ini dan pasti bayar. Deposit bisa pakai Pulsa tanpa potongan. Login disini: klik disini semoga maxwin.

раскрутка сайта москва [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve115.ru/]раскрутка сайта москва[/url] .

Bu sene en çok kazandıran casino siteleri hangileri? Cevabı platformumuzda mevcuttur. Bedava bahis veren siteleri ve yeni adres linklerini paylaşıyoruz. İncelemek için [url=https://cassiteleri.us.org/#]siteyi incele[/url] fırsatı kaçırmayın.

интернет раскрутка [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve119.ru/]интернет раскрутка[/url] .

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtarırsınızsa, doğru yerdesiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə hesabınıza girin və qazanmağa başlayın. Xoş gəldin bonusu sizi gözləyir. Keçid: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]pinupaz.jp.net[/url] qazancınız bol olsun.

Bocoran slot gacor hari ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Situs ini anti rungkad dan aman. Promo menarik menanti anda. Kunjungi: п»їbonaslotind.us.com dan menangkan.

Pin Up Casino ölkəmizdə ən populyar platformadır. Saytda minlərlə oyun və Aviator var. Pulu kartınıza tez köçürürlər. Proqramı də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Rəsmi sayt pinupaz.jp.net yoxlayın.

Merhaba arkadaşlar, sağlam casino siteleri arıyorsanız, hazırladığımız listeye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve bonusları sizin için listeledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: en iyi casino siteleri iyi kazançlar.

Yeni Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, bura baxa bilərsiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə qeydiyyat olun və oynamağa başlayın. Pulsuz fırlanmalar sizi gözləyir. Keçid: https://pinupaz.jp.net/# ətraflı məlumat hamıya bol şans.

интернет раскрутка [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve115.ru/]интернет раскрутка[/url] .

Salam Gacor, lagi nyari situs slot yang mudah menang? Coba main di Bonaslot. Winrate tertinggi hari ini dan terbukti membayar. Isi saldo bisa pakai Dana tanpa potongan. Daftar sekarang: slot gacor hari ini semoga maxwin.

продвинуть сайт в москве [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve119.ru/]продвинуть сайт в москве[/url] .

Selam, ödeme yapan casino siteleri arıyorsanız, hazırladığımız listeye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve fırsatları sizin için inceledik. Dolandırılmamak için doğru adres: casino siteleri 2026 iyi kazançlar.

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, doğru yerdesiniz. İşlək link vasitəsilə qeydiyyat olun və oynamağa başlayın. Xoş gəldin bonusu sizi gözləyir. Keçid: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]Pin Up AZ[/url] hamıya bol şans.

Situs Bonaslot adalah bandar judi slot online nomor 1 di Indonesia. Banyak member sudah mendapatkan Jackpot sensasional disini. Transaksi super cepat hanya hitungan menit. Link alternatif п»їhttps://bonaslotind.us.com/# situs slot resmi gas sekarang bosku.

Canlı casino oynamak isteyenler için kılavuz niteliğinde bir site: güvenilir casino siteleri Hangi site güvenilir diye düşünmeyin. Onaylı bahis siteleri listesi ile sorunsuz oynayın. Tüm liste linkte.

продвижение сайтов во франции [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve115.ru/]продвижение сайтов во франции[/url] .

Yeni Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, doğru yerdesiniz. İşlək link vasitəsilə hesabınıza girin və qazanmağa başlayın. Xoş gəldin bonusu sizi gözləyir. Keçid: https://pinupaz.jp.net/# sayta keçid qazancınız bol olsun.

поисковое продвижение москва профессиональное продвижение сайтов [url=https://prodvizhenie-sajtov-v-moskve119.ru/]поисковое продвижение москва профессиональное продвижение сайтов[/url] .

Pin Up Casino ölkəmizdə ən populyar platformadır. Burada minlərlə oyun və canlı dilerlər var. Qazancı kartınıza anında köçürürlər. Proqramı də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Giriş linki https://pinupaz.jp.net/# Pin Up yüklə tövsiyə edirəm.

Pin-Up AZ Azərbaycanda ən populyar platformadır. Burada çoxlu slotlar və canlı dilerlər var. Pulu kartınıza anında köçürürlər. Proqramı də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Rəsmi sayt [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]pinupaz.jp.net[/url] yoxlayın.

Hər vaxtınız xeyir, siz də keyfiyyətli kazino axtarırsınızsa, mütləq Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Yüksək əmsallar və sürətli ödənişlər burada mövcuddur. Qeydiyyatdan keçin və bonus qazanın. Daxil olmaq üçün link: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]Pin Up online[/url] uğurlar hər kəsə!

Salam dostlar, siz də keyfiyyətli kazino axtarırsınızsa, məsləhətdir ki, Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Ən yaxşı slotlar və sürətli ödənişlər burada mövcuddur. İndi qoşulun və ilk depozit bonusunu götürün. Sayta keçmək üçün link: Pin Up online uğurlar hər kəsə!

Selamlar, ödeme yapan casino siteleri arıyorsanız, bu siteye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve bonusları sizin için inceledik. Dolandırılmamak için doğru adres: https://cassiteleri.us.org/# cassiteleri.us.org bol şanslar.

**prodentim**

prodentim is a distinctive oral-care formula that pairs targeted probiotics with plant-based ingredients to encourage strong teeth, comfortable gums, and reliably fresh breath.

Info slot gacor hari ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Situs ini gampang menang dan aman. Bonus new member menanti anda. Akses link: https://bonaslotind.us.com/# slot gacor hari ini dan menangkan.

Info slot gacor malam ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Situs ini gampang menang dan resmi. Promo menarik menanti anda. Kunjungi: п»ї[url=https://bonaslotind.us.com/#]bonaslotind.us.com[/url] raih kemanangan.

Situs Bonaslot adalah agen judi slot online terpercaya di Indonesia. Ribuan member sudah mendapatkan Maxwin sensasional disini. Proses depo WD super cepat kilat. Link alternatif п»їhttps://bonaslotind.us.com/# bonaslotind.us.com gas sekarang bosku.

Salam dostlar, əgər siz keyfiyyətli kazino axtarırsınızsa, məsləhətdir ki, Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Yüksək əmsallar və sürətli ödənişlər burada mövcuddur. Qeydiyyatdan keçin və bonus qazanın. Oynamaq üçün link: Pin Up online uğurlar hər kəsə!

Bu sene en çok kazandıran casino siteleri hangileri? Detaylı liste web sitemizde mevcuttur. Bedava bahis veren siteleri ve yeni adres linklerini paylaşıyoruz. Hemen tıklayın https://cassiteleri.us.org/# bonus veren siteler fırsatı kaçırmayın.

**revitag**

revitag is a daily skin-support formula created to promote a healthy complexion and visibly diminish the appearance of skin tags.

**blood armor**

BloodArmor is a research-driven, premium nutritional supplement designed to support healthy blood sugar balance, consistent daily energy, and long-term metabolic strength

п»їHalo Bosku, cari situs slot yang gacor? Coba main di Bonaslot. Winrate tertinggi hari ini dan pasti bayar. Deposit bisa pakai Pulsa tanpa potongan. Daftar sekarang: п»їhttps://bonaslotind.us.com/# slot gacor hari ini salam jackpot.

Halo Bosku, cari situs slot yang mudah menang? Coba main di Bonaslot. RTP Live tertinggi hari ini dan pasti bayar. Isi saldo bisa pakai OVO tanpa potongan. Login disini: [url=https://bonaslotind.us.com/#]slot gacor hari ini[/url] salam jackpot.

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtarırsınızsa, bura baxa bilərsiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə qeydiyyat olun və oynamağa başlayın. Pulsuz fırlanmalar sizi gözləyir. Keçid: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]sayta keçid[/url] uğurlar.

**mounjaboost**

MounjaBoost next-generation, plant-based supplement created to support metabolic activity, encourage natural fat utilization, and elevate daily energywithout extreme dieting or exhausting workout routines.

п»їSalam Gacor, lagi nyari situs slot yang hoki? Rekomendasi kami adalah Bonaslot. RTP Live tertinggi hari ini dan terbukti membayar. Isi saldo bisa pakai Dana tanpa potongan. Daftar sekarang: п»їbonaslotind.us.com semoga maxwin.

Bocoran slot gacor hari ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Website ini gampang menang dan resmi. Promo menarik menanti anda. Akses link: klik disini dan menangkan.

Salamlar, əgər siz yaxşı kazino axtarırsınızsa, məsləhətdir ki, Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Yüksək əmsallar və sürətli ödənişlər burada mövcuddur. İndi qoşulun və bonus qazanın. Daxil olmaq üçün link: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]Pin Up yüklə[/url] uğurlar hər kəsə!

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtarırsınızsa, doğru yerdesiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə hesabınıza girin və oynamağa başlayın. Xoş gəldin bonusu sizi gözləyir. Keçid: https://pinupaz.jp.net/# Pin Up uğurlar.

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtarırsınızsa, bura baxa bilərsiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə hesabınıza girin və oynamağa başlayın. Pulsuz fırlanmalar sizi gözləyir. Keçid: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]ətraflı məlumat[/url] hamıya bol şans.

Canlı casino oynamak isteyenler için rehber niteliğinde bir site: türkçe casino siteleri Nerede oynanır diye düşünmeyin. Editörlerimizin seçtiği casino siteleri listesi ile rahatça oynayın. Tüm liste linkte.

Salamlar, É™gÉ™r siz keyfiyyÉ™tli kazino axtarırsınızsa, mÉ™slÉ™hÉ™tdir ki, Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Æn yaxşı slotlar vÉ™ sürÉ™tli ödÉ™niÅŸlÉ™r burada mövcuddur. Qeydiyyatdan keçin vÉ™ bonus qazanın. Oynamaq üçün link: https://pinupaz.jp.net/# bura daxil olun uÄŸurlar hÉ™r kÉ™sÉ™!

Selamlar, sağlam casino siteleri arıyorsanız, bu siteye mutlaka göz atın. Lisanslı firmaları ve fırsatları sizin için listeledik. Dolandırılmamak için doğru adres: https://cassiteleri.us.org/# cassiteleri.us.org bol şanslar.

Yeni Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, doğru yerdesiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə hesabınıza girin və oynamağa başlayın. Pulsuz fırlanmalar sizi gözləyir. Keçid: [url=https://pinupaz.jp.net/#]bura daxil olun[/url] hamıya bol şans.

**men balance pro**

MEN Balance Pro is a high-quality dietary supplement developed with research-informed support to help men maintain healthy prostate function.

Hər vaxtınız xeyir, siz də yaxşı kazino axtarırsınızsa, məsləhətdir ki, Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Ən yaxşı slotlar və rahat pul çıxarışı burada mövcuddur. Qeydiyyatdan keçin və ilk depozit bonusunu götürün. Oynamaq üçün link: Pin-Up Casino uğurlar hər kəsə!

Hi, To be honest, I found a useful online drugstore where you can buy medications cheaply. If you need safe pharmacy delivery, this store is the best choice. Secure shipping and no script needed. Link here: [url=https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#]cheap pharmacy online[/url]. Peace.

To be honest, Lately came across a useful online drugstore for cheap meds. If you want to buy ED meds without prescription, this store is worth checking. It has secure delivery worldwide. Check it out: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]order medicines from india[/url]. Best regards.

Hi, To be honest, I found a useful international pharmacy for purchasing generics online. For those who need safe pharmacy delivery, OnlinePharm is very good. They ship globally plus it is very affordable. See for yourself: click here. Have a good one.

Hey guys, I just found the best Indian pharmacy for affordable pills. For those looking for generic pills at factory prices, this store is worth checking. They offer secure delivery guaranteed. Check it out: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]cheap indian generics[/url]. Best regards.

Hi, I wanted to share a useful website where you can buy medications online. If you need antibiotics, OnlinePharm is the best choice. They ship globally plus it is very affordable. Visit here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Thx.

Greetings, I just found an amazing online drugstore to save on Rx. If you want to buy generic pills without prescription, IndiaPharm is the best place. It has lowest prices guaranteed. Take a look: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]safe indian pharmacy[/url]. Best regards.

Hello, I wanted to share a useful website where you can buy prescription drugs cheaply. For those who need antibiotics, OnlinePharm is highly recommended. They ship globally plus it is very affordable. Check it out: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Cheers.

раскрутка и продвижение сайта [url=https://poiskovoe-seo-v-moskve.ru/]раскрутка и продвижение сайта[/url] .

seo статьи [url=https://statyi-o-marketinge2.ru/]seo статьи[/url] .

Greetings, I recently found a trusted online source for affordable pills. If you are tired of high prices and need meds from Mexico, this site is highly recommended. Great prices plus secure. Link is here: [url=https://pharm.mex.com/#]cheap antibiotics mexico[/url]. Thank you.

Greetings, I wanted to share an excellent website to order prescription drugs cheaply. If you need cheap meds, this store is highly recommended. Great prices plus it is very affordable. See for yourself: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Cheers.

Hey guys, Just now discovered a useful online drugstore for cheap meds. If you want to buy ED meds at factory prices, IndiaPharm is highly recommended. It has wholesale rates guaranteed. More info here: IndiaPharm. Hope it helps.

Greetings, I just found a great source for meds for purchasing pills hassle-free. If you are looking for safe pharmacy delivery, this store is very good. Fast delivery and it is very affordable. See for yourself: safe online drugstore. Stay safe.

Hello, Lately stumbled upon a great Indian pharmacy to save on Rx. For those looking for generic pills cheaply, this store is highly recommended. It has wholesale rates guaranteed. Take a look: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]safe indian pharmacy[/url]. Good luck.

Hi guys, I recently found a reliable Mexican pharmacy for cheap meds. If you are tired of high prices and need generic drugs, Pharm Mex is highly recommended. No prescription needed and secure. Check it out: cheap antibiotics mexico. Best regards.

Greetings, I just found an excellent website for purchasing prescription drugs online. If you are looking for safe pharmacy delivery, OnlinePharm is worth a look. Great prices plus it is very affordable. Link here: [url=https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#]this site[/url]. Good luck with everything.

оптимизация и seo продвижение сайтов москва [url=https://poiskovoe-seo-v-moskve.ru/]оптимизация и seo продвижение сайтов москва[/url] .

digital маркетинг блог [url=https://statyi-o-marketinge2.ru/]statyi-o-marketinge2.ru[/url] .

Hi, I wanted to share a great source for meds where you can buy prescription drugs online. If you are looking for cheap meds, this site is highly recommended. Fast delivery plus it is very affordable. Link here: [url=https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#]cheap pharmacy online[/url]. Thank you.

Hello everyone, Lately ran into a great Mexican pharmacy to save on Rx. If you want to save money and need cheap antibiotics, Pharm Mex is highly recommended. No prescription needed plus secure. Visit here: [url=https://pharm.mex.com/#]this site[/url]. Take care.

To be honest, Lately found a reliable resource for affordable pills. For those seeking and need affordable prescriptions, Pharm Mex is a game changer. They ship to USA plus secure. Visit here: pharm.mex.com. Thank you.

Hey everyone, I recently discovered a great source for meds for purchasing generics online. If you need antibiotics, this store is very good. Fast delivery and it is very affordable. Link here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Have a good one.

Greetings, I recently discovered a great online drugstore to save on Rx. If you need ED meds at factory prices, this site is highly recommended. It has wholesale rates to USA. Take a look: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Cheers.

Greetings, I recently discovered a useful source for meds to order medications hassle-free. For those who need antibiotics, this site is worth a look. They ship globally and it is very affordable. Check it out: [url=https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#]onlinepharm.jp.net[/url]. Cya.

продвижение веб сайтов москва [url=https://poiskovoe-seo-v-moskve.ru/]продвижение веб сайтов москва[/url] .

блог про seo [url=https://statyi-o-marketinge2.ru/]statyi-o-marketinge2.ru[/url] .

Hey everyone, I recently discovered a useful website for purchasing generics online. If you need no prescription drugs, this site is very good. Great prices plus no script needed. Link here: [url=https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#]cheap pharmacy online[/url]. Have a great week.

To be honest, I just ran into a reliable Mexican pharmacy for cheap meds. If you want to save money and want affordable prescriptions, this store is a game changer. No prescription needed plus very reliable. Visit here: Pharm Mex. Regards.

Hello everyone, I just ran into a trusted website to buy medication. For those seeking and want meds from Mexico, Pharm Mex is highly recommended. They ship to USA plus secure. Link is here: [url=https://pharm.mex.com/#]read more[/url]. Thanks!

Hi, I just found a great source for meds where you can buy generics hassle-free. For those who need antibiotics, this store is very good. Secure shipping plus it is very affordable. Check it out: [url=https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#]read more[/url]. Appreciate it.

Hey there, I recently ran into a great Mexican pharmacy for affordable pills. If you want to save money and want generic drugs, Pharm Mex is highly recommended. They ship to USA plus secure. Link is here: https://pharm.mex.com/#. Hope this was useful.

Greetings, To be honest, I found an excellent international pharmacy for purchasing prescription drugs online. For those who need no prescription drugs, OnlinePharm is worth a look. Fast delivery plus no script needed. Check it out: international pharmacy online. Thank you.

To be honest, I just discovered the best source from India for affordable pills. For those looking for generic pills without prescription, this site is worth checking. It has fast shipping to USA. Check it out: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]visit website[/url]. Best regards.

https://sonabet.pro/

продвижение сайтов интернет магазины в москве [url=https://poiskovoe-seo-v-moskve.ru/]продвижение сайтов интернет магазины в москве[/url] .

руководства по seo [url=https://statyi-o-marketinge2.ru/]statyi-o-marketinge2.ru[/url] .

Hey there, To be honest, I found a useful website to order generics online. For those who need antibiotics, this site is highly recommended. They ship globally plus it is very affordable. Visit here: Online Pharm Store. Regards.

Hey guys, I just stumbled upon a useful online drugstore to buy generics. If you need medicines from India without prescription, this store is very reliable. It has wholesale rates guaranteed. Check it out: indian pharmacy. Cheers.

Hey guys, Just now found a useful Indian pharmacy to save on Rx. For those looking for generic pills cheaply, this store is highly recommended. You get fast shipping worldwide. Check it out: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]IndiaPharm[/url]. Best regards.

**breathe**

breathe is a plant-powered tincture crafted to promote lung performance and enhance your breathing quality.

Hi, I just found a useful source for meds to order prescription drugs online. If you are looking for no prescription drugs, this store is the best choice. Secure shipping plus huge selection. See for yourself: international pharmacy online. Best regards.

Hey everyone, I just found a reliable website where you can buy prescription drugs cheaply. If you are looking for no prescription drugs, this site is worth a look. Great prices plus no script needed. See for yourself: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Hope this helps!

Hi all, Just now found an amazing Indian pharmacy for cheap meds. If you want to buy ED meds without prescription, this site is very reliable. It has fast shipping worldwide. Check it out: read more. Good luck.

Hello, I wanted to share a great source for meds to order pills online. If you need cheap meds, this site is the best choice. Great prices and no script needed. Visit here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Sincerely.

Hello everyone, Lately came across a trusted website for cheap meds. If you are tired of high prices and want affordable prescriptions, this site is worth checking out. They ship to USA plus it is safe. Take a look: https://pharm.mex.com/#. Thank you.

Hi all, Lately found a great source from India for cheap meds. If you want to buy ED meds without prescription, this site is very reliable. It has lowest prices worldwide. Take a look: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Good luck.

Hello, To be honest, I found a useful online drugstore where you can buy generics cheaply. For those who need antibiotics, this store is highly recommended. Secure shipping and no script needed. See for yourself: click here. Many thanks.

Hi, I wanted to share an excellent source for meds to order medications securely. If you are looking for no prescription drugs, OnlinePharm is highly recommended. Great prices plus huge selection. See for yourself: online pharmacy usa. I hope you find what you need.

Hey there, I just found a great source for meds where you can buy pills securely. For those who need antibiotics, OnlinePharm is the best choice. Great prices plus it is very affordable. Visit here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Thx.

Hey guys, I recently discovered a great online drugstore for affordable pills. If you need ED meds without prescription, this store is the best place. It has lowest prices worldwide. More info here: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]this site[/url]. Cheers.

Greetings, I wanted to share a useful international pharmacy to order prescription drugs cheaply. If you are looking for cheap meds, this site is worth a look. Secure shipping plus it is very affordable. Check it out: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. I hope you find what you need.

Hi all, Lately discovered a useful online drugstore for affordable pills. If you need ED meds without prescription, this store is the best place. They offer lowest prices to USA. Visit here: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]cheap indian generics[/url]. Best regards.

Hello everyone, Just now discovered a great resource for affordable pills. If you want to save money and need cheap antibiotics, this store is a game changer. No prescription needed and very reliable. Visit here: mexican pharmacy online. Hope it helps.

Hey everyone, I just found a useful source for meds for purchasing medications cheaply. If you need antibiotics, this store is the best choice. They ship globally plus no script needed. Check it out: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Have a good one.

Hi, I wanted to share a reliable international pharmacy to order generics online. If you need antibiotics, this store is highly recommended. Fast delivery plus huge selection. Check it out: Online Pharm Store. Hope it helps.

Hey everyone, To be honest, I found a useful website to order prescription drugs online. For those who need safe pharmacy delivery, this store is worth a look. Great prices and no script needed. Check it out: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Kind regards.

Hi all, I recently stumbled upon the best website for affordable pills. For those looking for generic pills without prescription, this store is very reliable. It has wholesale rates guaranteed. Take a look: India Pharm Store. Best regards.

Hey everyone, I just found a great online drugstore to order medications cheaply. If you are looking for cheap meds, this site is very good. Secure shipping and no script needed. Visit here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Cheers.

Hello everyone, I just came across an awesome website to save on Rx. If you are tired of high prices and need generic drugs, this store is worth checking out. Great prices and it is safe. Link is here: [url=https://pharm.mex.com/#]mexican pharmacy online[/url]. Best regards.

Hey there, I recently found a trusted resource for cheap meds. For those seeking and want meds from Mexico, this site is a game changer. No prescription needed plus it is safe. Check it out: [url=https://pharm.mex.com/#]mexican pharmacy online[/url]. Good luck with everything.

To be honest, I recently stumbled upon a useful Indian pharmacy to buy generics. For those looking for ED meds safely, this store is very reliable. It has fast shipping to USA. Take a look: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Hope it helps.

mostbet online [url=https://mostbet2026.help]mostbet online[/url]

Hey there, I recently discovered a reliable website to buy medication. If you are tired of high prices and want affordable prescriptions, this store is highly recommended. Great prices plus it is safe. Take a look: https://pharm.mex.com/#. Good luck!

Hey there, Lately found a great online source to buy medication. If you want to save money and want affordable prescriptions, Pharm Mex is a game changer. Great prices and secure. Link is here: [url=https://pharm.mex.com/#]this site[/url]. Hope this helps!

курс seo [url=https://kursy-seo-4.ru/]курс seo[/url] .

учиться seo [url=https://kursy-seo-5.ru/]kursy-seo-5.ru[/url] .

Hi all, Just now found the best Indian pharmacy to buy generics. If you want to buy ED meds cheaply, this site is highly recommended. They offer wholesale rates to USA. Visit here: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Hope it helps.

мостбет оригинал скачать [url=http://mostbet2026.help]мостбет оригинал скачать[/url]

To be honest, I just came across a great website to save on Rx. If you need medicines from India cheaply, this site is highly recommended. You get fast shipping worldwide. Take a look: order medicines from india. Best regards.

мостбет скачать бесплатно [url=https://www.mostbet2026.help]мостбет скачать бесплатно[/url]

seo интенсив [url=https://kursy-seo-4.ru/]seo интенсив[/url] .

курсы seo [url=https://kursy-seo-5.ru/]курсы seo[/url] .

Greetings, I just discovered an awesome online source for cheap meds. For those seeking and need meds from Mexico, this site is worth checking out. They ship to USA and it is safe. Check it out: this site. Appreciate it.

mostbet [url=https://mostbet2026.help]https://mostbet2026.help[/url]

Hello everyone, I just ran into a trusted resource to save on Rx. For those seeking and want cheap antibiotics, this site is the best option. No prescription needed plus very reliable. Link is here: [url=https://pharm.mex.com/#]safe mexican pharmacy[/url]. Many thanks.

To be honest, Lately found a reliable resource to buy medication. If you want to save money and need meds from Mexico, this site is a game changer. Great prices and very reliable. Check it out: Pharm Mex Store. Best of luck.

seo с нуля [url=https://kursy-seo-4.ru/]seo с нуля[/url] .

seo онлайн [url=https://kursy-seo-5.ru/]seo онлайн[/url] .

To be honest, Lately found the best website for cheap meds. If you need medicines from India at factory prices, IndiaPharm is the best place. They offer fast shipping guaranteed. More info here: [url=https://indiapharm.in.net/#]cheap indian generics[/url]. Hope it helps.

Herkese selam, Vaycasino kullan?c?lar? ad?na onemli bir bilgilendirme paylas?yorum. Bildiginiz gibi platform giris linkini yine degistirdi. Giris sorunu varsa endise etmeyin. Son Vay Casino giris adresi su an asag?dad?r: [url=https://vaycasino.us.com/#]Resmi Site[/url] Bu link ile vpn kullanmadan siteye girebilirsiniz. Lisansl? bahis keyfi surdurmek icin Vay Casino dogru adres. Tum forum uyelerine bol kazanclar temenni ederim.

школа seo [url=https://kursy-seo-4.ru/]школа seo[/url] .

Arkadaslar, Grandpashabet Casino son linki ac?kland?. Adresi bulamayanlar su linkten devam edebilir https://grandpashabet.in.net/#

Great post! I enjoyed reading this article because the information is clear and well organized. Thank you for sharing such helpful and insightful content with your audience.

курсы seo [url=https://kursy-seo-5.ru/]курсы seo[/url] .

Matbet TV giriş adresi lazımsa doğru yerdesiniz. Hızlı için: https://matbet.jp.net/# Yüksek oranlar bu sitede. Gençler, Matbet yeni adresi belli oldu.

Matbet güncel linki arıyorsanız doğru yerdesiniz. Maç izlemek için: https://matbet.jp.net/# Yüksek oranlar burada. Gençler, Matbet yeni adresi açıklandı.

Herkese merhaba, Vay Casino kullan?c?lar? icin onemli bir duyuru yapmak istiyorum. Bildiginiz gibi platform giris linkini tekrar degistirdi. Giris sorunu yas?yorsan?z endise etmeyin. Son siteye erisim linki art?k burada: Vaycasino Indir Bu link ile direkt hesab?n?za girebilirsiniz. Guvenilir bahis deneyimi surdurmek icin Vay Casino dogru adres. Tum forum uyelerine bol sans dilerim.

Grandpasha güncel adresi lazımsa doğru yerdesiniz. Hızlı giriş yapmak için tıkla https://grandpashabet.in.net/# Yüksek oranlar burada.

Dostlar selam, bu site oyuncular? icin k?sa bir duyuru yapmak istiyorum. Bildiginiz gibi Vaycasino adresini tekrar degistirdi. Giris hatas? varsa panik yapmay?n. Guncel Vay Casino giris linki art?k burada: https://vaycasino.us.com/# Bu link uzerinden dogrudan siteye erisebilirsiniz. Guvenilir casino deneyimi surdurmek icin Vay Casino dogru adres. Tum forum uyelerine bol kazanclar dilerim.

Grandpasha güncel adresi lazımsa işte burada. Sorunsuz giriş yapmak için tıkla Grandpashabet Twitter Deneme bonusu bu sitede.

Grandpasha giris linki laz?msa dogru yerdesiniz. Sorunsuz erisim icin https://grandpashabet.in.net/# Yuksek oranlar burada.

Matbet TV giriş adresi lazımsa işte burada. Maç izlemek için tıkla: https://matbet.jp.net/# Yüksek oranlar burada. Gençler, Matbet yeni adresi açıklandı.