The Day the Desert Remembered: Timbuktu’s Manuscripts Rise Again

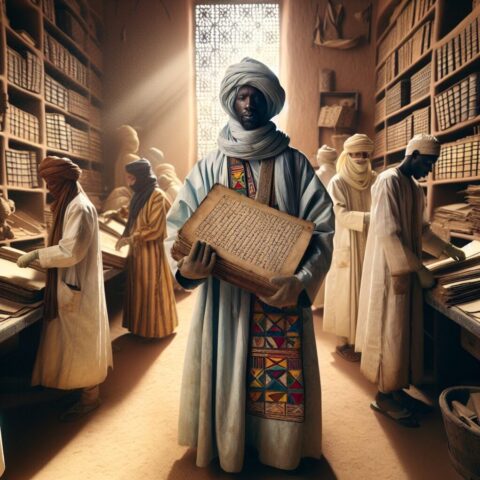

Opening Scene: Dust, Light, and the Hum of Return

The room is quiet enough to hear the brush, bristle by bristle, as a conservator lifts centuries-old sand from the margin of a page. There is a steady hum from the generator outside. Afternoon light slices through earthen windows, turning the air into a soft veil that catches each floating grain. A finger presses the edge of a torn binding, then releases, testing the paper’s spring. It is not brittle. It is not weak. It is alive. In Timbuktu, the desert remembers, and people listen.

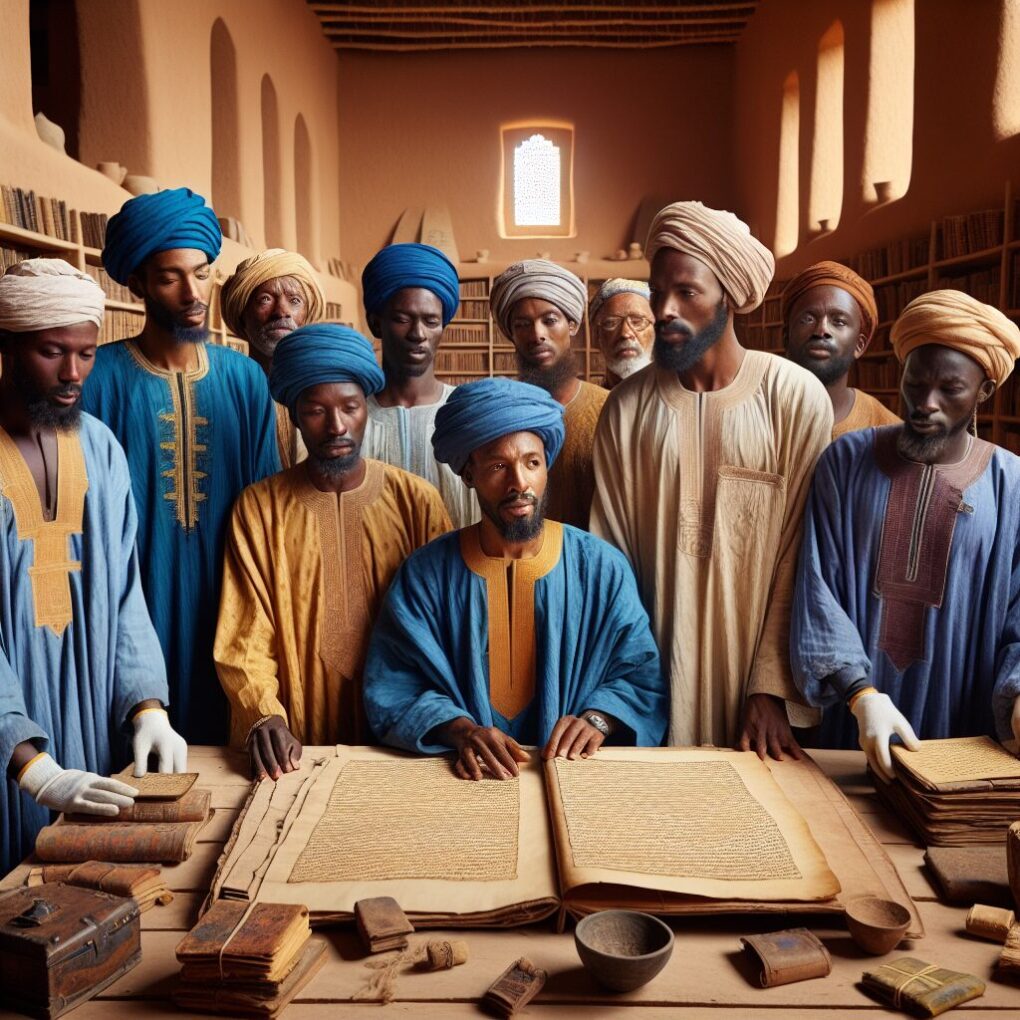

On a long table, a manuscript rests open to a page of astronomy, delicate circles marked with numbers, notes in the margins written in a hand that knew the stars. In one corner, a team prepares a camera rig, the kind used to capture paintings in galleries. They call out readings for humidity, 48 percent, temperature, a steady 24 degrees Celsius, safe for paper. A postcard of the Niger River is pinned to the corkboard, blue against the tan walls, a reminder that the desert is not only sand, it is water hidden under memory.

What Survived and How: The Quiet Rescue

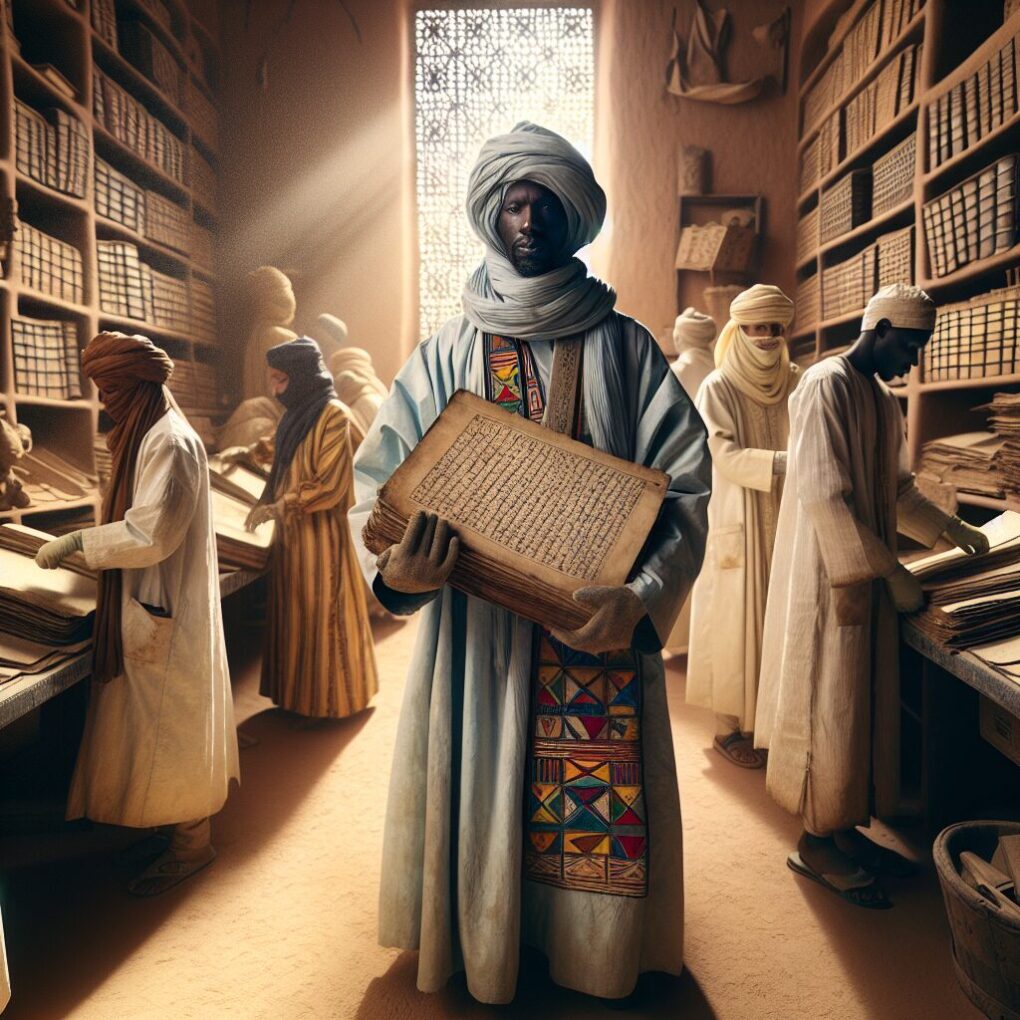

A decade ago, these pages could have been ashes floating in a hot wind. In 2012, as militants moved on Timbuktu and set their sights on what they called forbidden knowledge, families who had guarded manuscripts for generations decided to take a risk that most people would never see, much less survive. Teachers, librarians, boatmen, teachers again, because in this city one person can be many things, labored through the night. They packed rag paper and camel-leather bindings into metal trunks, box after box, in courtyards where only the moon and their fear could see.

Abdel Kader Haidara, raised in one of Timbuktu’s famed family libraries, became a public face of this work, yet it was a network that made the rescue possible. Drivers willing to cross checkpoints. Mothers and daughters who wrapped volumes in cloth, then set them behind sacks of rice. Boatmen who pushed off from shallow banks as the sun lifted over the Niger. People who knew that saving a book is not only about literacy, it is about dignity, and lineage, and refusing to forget. By the time militants torched part of the Ahmed Baba Institute in early 2013, more than 350,000 manuscripts had already traveled south to Bamako in metal trunks that looked ordinary to anyone who did not know their weight.

In Bamako, the rescue did not end. It changed form. Rooms were turned into storage areas. Wood slats lifted trunks off damp floors. Desiccant packets, fans, and dehumidifiers carved a fragile pocket of safety out of a tropical climate. The work was hidden in plain sight, and if you asked, you would hear a calm answer, we are caretakers, nothing more.

A Human Story: Aïssata at the Table

There is a young conservator in the Bamako lab that many colleagues call the steady hand. Aïssata is a composite of several women I met in that laboratory, a single story braided from many voices so no one person carries the burden of being named. She studied chemistry at a public university in the south, then returned to the capital because her uncle had worked as a scribe in Timbuktu, copying long treatises in a small room behind a blue door. Her first months were mostly cleaning. No solvents. No adhesives. Just breath and patience and a brush. She learned to feel the difference between sand and mold under her fingertips, to hear the faint rasp of a page that did not sound right, a page that needed to rest.

One afternoon, a trunk arrived with pages fused at the edges. The room smelled faintly of rain caught in fabric, a sign of moisture trapped too long. Aïssata tested fibers with distilled water and a wheat starch paste, then separated each sheet with Japanese kozo tissue, paper as thin as a sigh yet stronger than it looked. Hours passed. Someone turned the radio low. The generator kept breathing. When the last page lifted free, no tearing, no loss, Aïssata smiled with her whole face. The lab clapped, a quiet celebration. That night she walked home under the neon of Bamako traffic, shoulders sore, satisfied. She was not just saving books. She was returning voices to a city that had been told to forget itself.

What Is Happening Now: From Storage to Digitization

The rescue was phase one. Today, the work has matured into a mesh of restoration labs, humidity-controlled archives, and large-scale digitization led by Malian institutions with support from UNESCO partners and global archives. If the desert remembers, servers remember too.

In Bamako and Timbuktu, conservation teams stabilize bindings, flatten warped pages, and document each volume’s provenance using standard archival metadata. Catalogers record script styles, languages, watermarks, and annotations. Many manuscripts are in Arabic, others in Ajami, African languages written in Arabic script, including Songhay and Tamasheq. Some are bound in soft goatskin leather with dyed flaps that wrap around like a folded hand. Many come with notes inserted by past readers, receipts, poems, weather observations, as if they knew we would need more than the main text to understand a life.

High-resolution cameras digitize folios under diffuse LED lighting. Conservators place a gentle weight on the page to avoid spine stress, then capture color targets that allow calibration later. The files are large, sometimes 300 to 600 megabytes per image, because each fiber matters. Partnerships with the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, the University of Cape Town’s Tombouctou Manuscripts Project, and platforms such as Google Arts and Culture have opened portals that let readers zoom into a 16th-century scholar’s marginal note from their phone. UNESCO’s programs have supported preservation training, environmental controls, and curriculum development that threads these resources into classrooms. The field has become both careful and expansive. It has invited the world in without giving away ownership.

Why These Pages Matter: A Written Africa in Full

Every time a technician turns a page, a myth loses altitude. These manuscripts are the physical rebuttal to the old fantasy that Africa had no books, only oral tradition. Timbuktu’s libraries documented law, geometry, astronomy, medicine, theology, biography, trade, and poetry. They recorded debates between jurists about market ethics, described surgical procedures and pharmacological recipes, mapped stars for navigation and prayer, and turned the emotional weather of daily life into verse. They argued about eclipse cycles and credit. They measured the land with words.

Scholars like Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti wrote legal opinions that circulated across the Sahara, connecting Timbuktu to Fez, Cairo, and beyond. Astronomical diagrams reveal complex understandings of planetary motion in local timekeeping. Medical treatises discuss the use of desert plants in poultices and infusions, descriptions that modern ethnobotanists study for insight into sustainable pharmacology. Some volumes include bilingual glosses, Arabic and Songhay or Tamasheq, a sign of a multilingual intellectual life that prefigures modern code-switching.

A city is what it remembers, and Timbuktu remembered in ink.

The People Behind the Work: Hands, Lineages, New Apprentices

These manuscripts did not preserve themselves. Family libraries have kept them safe for centuries, often in wooden chests or mud-brick alcoves above the floor to avoid floodwater. The new generation of caretakers knows both tradition and technique. Grandfathers and aunties who know how a book should feel. Young technicians, many of them women, trained in laboratory protocols and digital workflows. They repair joints with reversible adhesives so future conservators can remove their work without damage. They line torn paper with thin tissue, then redo sewing in patterns that match historical bindings. They photograph irregular watermarks under transmitted light to identify paper mills, a forensic touch that helps date volumes and track how knowledge moved along trade routes.

Documentation is as important as repair. Each item receives a stable identifier, a record of prior owners, notes on condition and content. The slow pace is not romanticism. It is ethics. Every choice, from the thickness of a tissue patch to the level of contrast in a scan, shapes how a future reader will see the past.

Fragile Future: Security, Climate, and the Long Haul

The work is heroic, but heroes need sleep, and projects need stability. Northern Mali remains volatile, with periodic conflict that complicates travel and planning. Security concerns make it risky to move materials back and forth, and they add costs that donors do not always see, escorts, secure vehicles, reinforced doors that still look like doors.

Climate pressure stresses everything. Timbuktu’s architecture, made from sun-dried mud brick and timber, swells and cracks with seasonal humidity and heat. Sandstorms drive fine dust into every crevice. Floods from the Niger’s seasonal rise can send moisture into lower walls. Archives fight mold with ventilation, air conditioning, and silica gel, but electricity is not a given. Generators drink fuel, and the price of fuel shapes the preservation of books written when fuel was a tree.

There is also the slow fragility of people in an intense environment. Conservators work with gloves, masks, and regular breaks, because prolonged exposure to mold spores affects respiratory health. Training pipelines must include not just collections care but occupational safety and mental health. The manuscripts will outlast any single human life, which is exactly why humans need structures that outlast any single grant.

Global Connection: Diaspora Readers, Open Access, New Curricula

Digitization has changed the audience and the conversation. Diaspora scholars and students can see pages that once sat behind a locked door in a private Timbuktu house. Teachers in Chicago or Lagos can pull a high-resolution image of a 17th-century commercial contract into a lesson on African trade, then ask their students to identify the clauses that protect a buyer. A poet in Dakar can zoom into marginalia where a scribe wrote, God forgive the mistakes, in a moment of weary humanity.

Open digital collections, when governed with respect for community ownership and cultural protocols, become bridges rather than extracts. They invite commentary, translation, and collaboration. Several projects now encourage annotations by scholars who can parse regional script forms or local references that outsiders would miss. Curriculum guides help teachers present these materials as central, not exotic, to the story of world knowledge.

The Next Chapter: Return, Expansion, and Measurable Milestones

The vision is clear. Stabilize, digitize, teach, then let the collections breathe again in Timbuktu under conditions that keep them safe. Plans are underway to strengthen local archives with improved environmental controls and training for a new cohort of conservators. Community-run libraries, long the backbone of this ecosystem, will continue to host study circles and visiting students. Digitization targets provide accountability and momentum, numbers like 100,000 folios imaged to international standards in the next three years, with metadata in French, Arabic, and English, and, when possible, in regional languages.

This is not nostalgia. It is infrastructure. The manuscripts will return not to vitrines that silence them, but to rooms where readers turn pages with clean hands and curiosity, where the sound you hear is the soft shuffle of learning.

Health of Heritage, Health of People

Our work often explores how bodies heal and how relationships grow. Here, the patient is a city’s memory, and the clinic is a lab where a person’s breath steadies the page. Preservation is not separate from public health. It depends on good air, clean water, reliable power, and the emotional resilience of teams that know their work matters beyond a news cycle. When a conservator steps away from a microscope to stretch, when a librarian closes her eyes for a minute after logging the last folio of the day, that is also the health of the project. The manuscripts teach us about balance, even as they demand long hours.

How This Story Differs From Our Usual Topics

If you have been following our essays on personal wellbeing, intimacy science, and the choreography of daily health, you might feel a different pulse here. The Timbuktu story draws on the same human senses, touch, breath, time, but it moves through libraries instead of clinics. Where our pieces on sleep, nutrition, or relationships focus on the biology of the present tense, this piece insists that a healthy society carries its history forward. The overlap is intentional. Care is care, whether for a body that needs rest or a page that needs light from the right angle. The difference is scale, and the patient, who this time is a city and a tradition.

Return to the Opening Room

Afternoon slips toward evening. The generator stutters, then steadies. A conservator adjusts the camera, captures a final image, and notes the file name. A blue cloth is folded into the trunk for cushioning. There is sand on the table, not much, because the brush has done its work. Outside, the sky is pink, then gold, then quiet. Timbuktu breathes. So do we.

Call to Action

Where do you place your hands when you care for what you love, on a shoulder, on a page, on a future plan that outlives you? If this story moved you, explore the digitized collections, share them with a student, and consider supporting the labs that turn quiet heroism into lasting memory.

References and Further Reading

- Hammer, J. The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu. Simon and Schuster, 2016.

- UNESCO. Timbuktu Manuscripts, Preservation Efforts and Programmes. UNESCO resources and reports, accessed 2024. https://www.unesco.org

- SAVAMA-DCI, Association for the Safeguarding and Valorization of the Manuscripts for the Defense of Islamic Culture. Project updates and preservation activities, accessed 2024. https://www.savama-dci.com

- Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, vHMML Reading Room, Timbuktu Collections. Ongoing digitization and catalog entries, accessed 2024. https://www.vhmml.org

- Tombouctou Manuscripts Project, University of Cape Town. Research on West African written traditions, accessed 2024. https://www.tombouctoumanuscripts.org

- Google Arts and Culture, Mali Magic. Digital exhibition and tens of thousands of high-resolution manuscript images, launched 2022. https://artsandculture.google.com/project/mali-magic

- ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Earthen Architectural Heritage, Guidelines on the Conservation of Earthen Structures. Climate risks and preservation strategies, accessed 2024. https://www.earthstructures.org

- Library of Congress. Manuscripts of Timbuktu, backgrounder on content and historical context, accessed 2024. https://www.loc.gov

Boost your well-being with a professional massage. It’s truly rejuvenating.

Nice blog here Also your site loads up fast What host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

Bosphorus sunset cruise Comfortable walking pace and breaks. https://wellboringgw.org/2012/10/18/istanbul-eco-tours-sustainable-travel-in-the-city/

Hi there to all, for the reason that I am genuinely keen of reading this website’s post to be updated on a regular basis. It carries pleasant stuff.

istanbul escort

Istanbul hidden gems tour Tour included everything we wanted to see. https://blackhorsepuzzle.com/?p=5727

Istanbul Archaeological Museum tour Tour included everything we wanted to see. https://meherpurbarta.com/?p=6490

Your blog is a treasure trove of valuable insights and thought-provoking commentary. Your dedication to your craft is evident in every word you write. Keep up the fantastic work!

Your articles never fail to captivate me. Each one is a testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with the world.

I very delighted to find this internet site on bing, just what I was searching for as well saved to fav

A massage is a fantastic way to soothe sore muscles. It helps your body recover faster.

This is a great way to manage stress. A regular massage can be a game-changer.

Hi Neat post Theres an issue together with your web site in internet explorer may test this IE still is the marketplace chief and a good component of people will pass over your fantastic writing due to this problem

Istanbul Old City tour Loved the mix of modern and historical spots. https://bannockburnadvisory.com/?p=4577

Pera Museum tour Istanbul Tours made our trip stress-free. https://gyldigitalsolution.com/?p=14680

Thank you I have just been searching for information approximately this topic for a while and yours is the best I have found out so far However what in regards to the bottom line Are you certain concerning the supply

Istanbul Modern Art Museum tour The boat tour on the Bosphorus was unforgettable. https://martinexteriordetailing.com/?p=20395

Use casino mirror for uninterrupted gameplay

Çağra LTD | Mutfak ürünleri | Bahçe aksesuar Kıbrıs mutfak gereçleri, hırdavat kıbrıs, kıbrıs hırdavat, matkap kıbrıs, kıbrıs inşaat ürünleri, kıbrıs mobilya

becem travel | Kıbrıs araç transfer Kıbrıs araç kiralama , Kıbrıs vip araç , Kıbrıs araç transfer , Kıbrıs güvenli ulaşım

Bence herkesin görmesi gerektiğini düşünüyorum, özgün faydalı samimi gerçekten güzel, böyle içerikleri görmek beni mutlu ediyor.

Bitstarz Casino brings you closer to jackpots.

Play, win, and enjoy the Aviator game on mobile or PC.

Perfect great random boring fantastic crazy interesting love bad fantastic funny wonderful love bad helpful.

Bence tasarımı da içeriği de mükemmel, net özgün oldukça gerçekten güzel, emeğinize sağlık, çok teşekkür ederim.

Ada dil| Kıbrıs İngilizce kursu ücretsiz İngilizce kursu , Kıbrıs çocuklar için İngilizce kursu, Kıbrıs online ingilizce , İngilizce eğitim setleri

Your ability to distill complex concepts into digestible nuggets of wisdom is truly remarkable. I always come away from your blog feeling enlightened and inspired. Keep up the phenomenal work!

Istanbul food guide Istanbul Tours gave us memories that will last forever. https://concepcion.skincenter.cl/?p=6977

Istanbul Bosphorus tour Our guide was funny and made the day enjoyable. https://martinexteriordetailing.com/?p=20395

Private yacht tour Istanbul The tour was family-friendly and easy to follow. https://srawal.com/?p=13928

Somebody essentially help to make significantly articles Id state This is the first time I frequented your web page and up to now I surprised with the research you made to make this actual post incredible Fantastic job

https://www.oneclickatdoorstep.com/product/pvp-crystals

My brother suggested I might like this blog He was totally right This post actually made my day You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this info Thanks

Hi my family member I want to say that this post is awesome nice written and come with approximately all significant infos I would like to peer extra posts like this

helloI really like your writing so a lot share we keep up a correspondence extra approximately your post on AOL I need an expert in this house to unravel my problem May be that is you Taking a look ahead to see you

İstanbul tesisat su kaçağı tespiti Beylikdüzü’ndeki apartmandaki su kaçağını bulmalar çok zordu, ancak bu ekip başardı. https://youslade.com/read-blog/102635

I do trust all the ideas youve presented in your post They are really convincing and will definitely work Nonetheless the posts are too short for newbies May just you please lengthen them a bit from next time Thank you for the post

Istanbul Ottoman history tour Learned a lot about Ottoman history. https://landrautovt.com/?p=2504

Thanks for simplifying a topic I’ve always found confusing. Your examples made everything click for me.

Istanbul half day tour Istanbul’s mix of East and West is best seen on a city tour. https://fanoosalinarah.com/?p=177647

Your blog is a true hidden gem on the internet. Your thoughtful analysis and engaging writing style set you apart from the crowd. Keep up the excellent work!

This is gold – thanks!

Stay in the game even when access is restricted � use a casino mirror.

Massages can help you sleep better and feel more rested. A real game-changer.

This was exactly what I was looking for.

Just do it—get a massage. You need that moment of peace.

Subscribed for more updates like this.

Massages are my secret to a stress-free life. It’s the best investment you can make in yourself.

You deserve to feel good. A massage is a great first step toward feeling better.

Yes! Get that massage.

I really enjoyed reading your post.

Yes! Get that massage.

It’s a fantastic way to unwind and reset your entire system. Try it today.

Kes – Mak Bahçe Aksesuarları ve Yedek Parça | Malatya benzinli testere yedek parça, testere zinciri, ağaç kesme pala, klavuz, elektronik bobin, hava filtresi, stihl malatya bayi

Robocombo Teknolojiarduino, drone ve bileşenler, drone parçaları

ФизиотерапияФизиотерапия, Рехабилитация, Мануална терапия, Хиропрактика, Лечебен масаж, Иглотерапия, Хиджама (Кръвни вендузи), Лазерна епилация, Антицелулитен масаж, Антицелулитни терапии

Good for you. A massage is a great choice.

Permission to get a massage granted. It’s your official day off!

Sigara Bırakma | Kc Psikolojimoraterapi, sigara bıraktırma, Rezonans

guided Istanbul tour Booking was super easy and smooth. https://wellboringgw.org/2012/10/18/istanbul-eco-tours-sustainable-travel-in-the-city/

Aydın Haber | Aydın Havadisleriaydın havadis haber, aydın haber, aydın haberleri, aydin haber

https://www.oneclickatdoorstep.com/product/a-pvp-crystals

Your blog is a testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. I’m constantly impressed by the depth of your knowledge and the clarity of your explanations. Keep up the amazing work!

Kadıköy food tour The tour gave us unforgettable memories. https://gurgaongraphics.in/?p=1058702

Bosphorus dinner cruise Great service, friendly guides, and comfortable transport. https://vividlipstudio.com/?p=1493

Download Aviator APK and start flying high

I wanted to take a moment to commend you on the outstanding quality of your blog. Your dedication to excellence is evident in every aspect of your writing. Truly impressive!

Your blog is a testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. I’m constantly impressed by the depth of your knowledge and the clarity of your explanations. Keep up the amazing work!

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I appreciate your blog. Your writing style is both engaging and informative, making it a pleasure to read. Looking forward to your future posts!

Your writing is like a breath of fresh air in the often stale world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging style set you apart from the crowd. Thank you for sharing your talents with us.

Your ability to distill complex concepts into digestible nuggets of wisdom is truly remarkable. I always come away from your blog feeling enlightened and inspired. Keep up the phenomenal work!

I was recommended this website by my cousin I am not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my trouble You are amazing Thanks

I simply could not go away your web site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard info a person supply on your guests Is going to be back incessantly to investigate crosscheck new posts

Topkapi Palace tour I enjoyed the photo stops at scenic spots. https://mytaxbizz.com/?p=27855

Your blog is a constant source of inspiration for me. Your passion for your subject matter shines through in every post, and it’s clear that you genuinely care about making a positive impact on your readers.

I do agree with all the ideas you have introduced on your post They are very convincing and will definitely work Still the posts are very short for newbies May just you please prolong them a little from subsequent time Thank you for the post

Balat walking tour Guides are friendly and knowledgeable. https://truwaymachinery.com/2012/10/18/istanbul-tours-unforgettable-journeys-through-history/

Your articles never fail to captivate me. Each one is a testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with the world.

Your blog is a testament to your dedication to your craft. Your commitment to excellence is evident in every aspect of your writing. Thank you for being such a positive influence in the online community.

Istanbul food tour Istanbul is so vibrant, and the tour showed us hidden gems. https://ticketiando.com/?p=8943

Thank you for sharing such a well-structured and easy-to-digest post. It’s not always easy to find content that strikes the right balance between informative and engaging, but this piece really delivered. I appreciated how each section built on the last without overwhelming the reader. Even though I’ve come across similar topics before, the way you presented the information here made it more approachable. I’ll definitely be returning to this as a reference point. It’s the kind of post that’s genuinely helpful no matter your level of experience with the subject. Looking forward to reading more of your work—keep it up! profis-vor-ort.de

Istanbul hidden gems tour Amazing memories from this city tour, thank you! https://adultxxxfunding.com/?p=27464

Sakıp Sabancı Museum tour I loved tasting Turkish tea during the tour. https://fertimedex.com/?p=4789

Turkish coffee tasting Istanbul Tours made our trip stress-free. https://landing.gifwebhosting.com/?p=7809

BitStarz Casino caters to different budgets with micro-stake slots, mid-range tables, and VIP options.

Chora Church tour The experience was smooth from start to finish. https://www.coaching-konstruktiv.de/?p=604

Istanbul culinary tour Excellent English and clear explanations. https://adhfp.org/?p=4157

Istanbul photography tour Every stop was picture-perfect! https://r1racegear.com/?p=22670

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing

Faydalı bilgilerinizi bizlerle paylaştığınız için teşekkür ederim.

Yazınız için teşekkürler. Bu bilgiler ışığında nice insanlar bilgilenmiş olacaktır.

Личный кабинет и статистика доступны через зеркало казино

How to Get Real Website Traffic & Earn Money Online | Free Traffic Machine 2025 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUvs6nBlBDQ – This method really works for getting real visitors and online income! (9)

naturally like your web site however you need to take a look at the spelling on several of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth on the other hand I will surely come again again.

Try a demo tutorial inside the Aviator game and graduate after a stable Aviator game download.

Kes – Mak Bahçe Aksesuarları ve Yedek Parça | Malatya benzinli testere yedek parça, testere zinciri, ağaç kesme pala, klavuz, elektronik bobin, hava filtresi, stihl malatya bayi

Play the Aviator game�provider background. Find a safe Aviator game download and quick tips on timing cashouts, limits, and fair play.

Evaluate latency spikes inside the Aviator game; reinstall from a clean Aviator game download if needed.

Mute distractions within the Aviator game and keep your Aviator game download source private.

Learn glossary terms specific to the Aviator game and store them with your Aviator game download guide.

Switch to lighter graphics for the Aviator game on older phones; use a legitimate Aviator game download and tweak settings.

Practice measured entries in the Aviator game; rely on a certified Aviator game download.

Learn quick-reconnect tricks in the Aviator game for drops; practice after a secure Aviator game download.

Compare energy saver modes that affect the Aviator game; record results by Aviator game download version.

https://www.oneclickatdoorstep.com/product/pvp-crystals

Really informative content. I’ve added https://pdfpanel.com to my toolkit.

Bosphorus day cruise Our English-speaking guide explained everything clearly. https://heladosgelana.com/?p=3740

Baklava tasting tour Worth every penny, truly memorable. https://hardmoneyloans.com/?p=16665

I’ve been following your blog for quite some time now, and I’m continually impressed by the quality of your content. Your ability to blend information with entertainment is truly commendable.

Istanbul Old City tour Our guide made history come alive during the old city walk. https://medilabspe.com/?p=3540

Topkapi Palace tour I recommend Istanbul tours to anyone visiting Turkey. https://www.dscc.lk/?p=2764

Kadıköy food tour I enjoyed the photo stops at scenic spots. https://planningdubai.ae/?p=12958

Hi i think that i saw you visited my web site thus i came to Return the favore I am attempting to find things to improve my web siteI suppose its ok to use some of your ideas

Its like you read my mind You appear to know so much about this like you wrote the book in it or something I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit but instead of that this is excellent blog A fantastic read Ill certainly be back

Somebody essentially lend a hand to make significantly articles Id state That is the very first time I frequented your website page and up to now I surprised with the research you made to make this actual submit amazing Wonderful task

This answered all my questions. 👉 Watch Live Tv online in HD. Stream breaking news, sports, and top shows anytime, anywhere with fast and reliable live streaming.

Your blog is a testament to your dedication to your craft. Your commitment to excellence is evident in every aspect of your writing. Thank you for being such a positive influence in the online community.

Your blog is a treasure trove of knowledge! I’m constantly amazed by the depth of your insights and the clarity of your writing. Keep up the phenomenal work!

Its like you read my mind You appear to know so much about this like you wrote the book in it or something I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit but instead of that this is excellent blog A fantastic read Ill certainly be back

Your articles never fail to captivate me. Each one is a testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with the world.

Your writing is like a breath of fresh air in the often stale world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging style set you apart from the crowd. Thank you for sharing your talents with us.

Lucky Jet game download gives full access to casino fun on mobile.

Chaque étudiant garde son certificat académique.

Aviator game is perfect for players who enjoy quick bets.

What i do not understood is in truth how you are not actually a lot more smartlyliked than you may be now You are very intelligent You realize therefore significantly in the case of this topic produced me individually imagine it from numerous numerous angles Its like men and women dont seem to be fascinated until it is one thing to do with Woman gaga Your own stuffs nice All the time care for it up

Le diplôme numérique est accepté.

I have been browsing online more than three hours today yet I never found any interesting article like yours It is pretty worth enough for me In my view if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did the internet will be a lot more useful than ever before

Your blog is a true hidden gem on the internet. Your thoughtful analysis and in-depth commentary set you apart from the crowd. Keep up the excellent work!

For 2025, this seems like the most updated article about random chat sites. See it here: best alternatives.

It’s rare to find a random chat site that doesn’t lag, but Uhmegle works smoothly even with video.

La grafica di Uhmegle è pulita, facile e intuitiva.

Ho letto di Uhmegle e l’ho provato, adesso lo consiglio a tutti. Vedi qui: link.

Safe download link: Uhmegle.org.

Most blogs online feel outdated, but this guide is very recent and gives real insights into which platforms work well.

What I like about this text chat option is that it’s really lightweight. It loads instantly and works even if my internet is slow.

One of the things I enjoy most about Uhmegle text chat is that you can stay anonymous while still having meaningful conversations.

Una alternativa muy buena a Omegle es Uhmegle, funciona bien tanto en móvil como en ordenador.

For 2025, this seems like the most updated article about random chat sites. See it here: best alternatives.

I used this page and had the app running in less than two minutes.

Hands down, this post is the best resource I’ve found this year.

Après avoir installé depuis ce lien, l’app marche parfaitement.

Top 2025 chat options in this article.

Unlike some other platforms, Uhmegle video doesn’t freeze or lag during calls. That makes the conversation flow much better.

After years of using random chat sites, I finally found Uhmegle.org. It feels safe, modern, and way more reliable than most alternatives.

Le grand avantage de ce site est qu’il ne demande pas d’inscription, on peut discuter immédiatement.

Me gusta la interfaz de Uhmegle, es limpia y fácil de usar.

I do not even know how I ended up here but I thought this post was great I dont know who you are but definitely youre going to a famous blogger if you arent already Cheers

I just could not leave your web site before suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard information a person supply to your visitors Is gonna be again steadily in order to check up on new posts

Your writing is like a breath of fresh air in the often stale world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging style set you apart from the crowd. Thank you for sharing your talents with us.

I just wanted to express my gratitude for the valuable insights you provide through your blog. Your expertise shines through in every word, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn from you.

Normally I do not read article on blogs however I would like to say that this writeup very forced me to try and do so Your writing style has been amazed me Thanks quite great post

Wow wonderful blog layout How long have you been blogging for you make blogging look easy The overall look of your site is great as well as the content

Your blog is a testament to your passion for your subject matter. Your enthusiasm is infectious, and it’s clear that you put your heart and soul into every post. Keep up the fantastic work!

I was recommended this website by my cousin I am not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my difficulty You are wonderful Thanks

Hi my loved one I wish to say that this post is amazing nice written and include approximately all vital infos Id like to peer more posts like this

Your writing is like a breath of fresh air in the often stale world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging style set you apart from the crowd. Thank you for sharing your talents with us.

Your blog is a constant source of inspiration for me. Your passion for your subject matter is palpable, and it’s clear that you pour your heart and soul into every post. Keep up the incredible work!

Your writing has a way of resonating with me on a deep level. I appreciate the honesty and authenticity you bring to every post. Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

I have been surfing online more than 3 hours today yet I never found any interesting article like yours It is pretty worth enough for me In my opinion if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did the web will be much more useful than ever before

My brother suggested I might like this blog He was totally right This post actually made my day You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this info Thanks

I do believe all the ideas youve presented for your post They are really convincing and will certainly work Nonetheless the posts are too short for novices May just you please lengthen them a little from subsequent time Thanks for the post

This was beautiful Admin. Thank you for your reflections.

obviously like your website but you need to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I to find it very troublesome to inform the reality on the other hand Ill certainly come back again

Your blog is a constant source of inspiration for me. Your passion for your subject matter shines through in every post, and it’s clear that you genuinely care about making a positive impact on your readers.

Your blog is a testament to your dedication to your craft. Your commitment to excellence is evident in every aspect of your writing. Thank you for being such a positive influence in the online community.

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing

Your blog is a beacon of light in the often murky waters of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Keep up the amazing work!

I do believe all the ideas youve presented for your post They are really convincing and will certainly work Nonetheless the posts are too short for novices May just you please lengthen them a little from subsequent time Thanks for the post

Your passion for your subject matter shines through in every post. It’s clear that you genuinely care about sharing knowledge and making a positive impact on your readers. Kudos to you!

Your blog is a beacon of light in the often murky waters of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Keep up the amazing work!

Its like you read my mind You appear to know so much about this like you wrote the book in it or something I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit but instead of that this is excellent blog A fantastic read Ill certainly be back

What i dont understood is in reality how youre now not really a lot more smartlyfavored than you might be now Youre very intelligent You understand therefore significantly in terms of this topic produced me personally believe it from a lot of numerous angles Its like women and men are not interested except it is one thing to accomplish with Woman gaga Your own stuffs outstanding Always care for it up

I loved as much as youll receive carried out right here The sketch is attractive your authored material stylish nonetheless you command get bought an nervousness over that you wish be delivering the following unwell unquestionably come more formerly again as exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike

Nice blog here Also your site loads up very fast What host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Hello Neat post Theres an issue together with your site in internet explorer would check this IE still is the marketplace chief and a large element of other folks will leave out your magnificent writing due to this problem

Your writing is like a breath of fresh air in the often stale world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging style set you apart from the crowd. Thank you for sharing your talents with us.

What i do not understood is in truth how you are not actually a lot more smartlyliked than you may be now You are very intelligent You realize therefore significantly in the case of this topic produced me individually imagine it from numerous numerous angles Its like men and women dont seem to be fascinated until it is one thing to do with Woman gaga Your own stuffs nice All the time care for it up

I do not even know how I ended up here but I thought this post was great I do not know who you are but certainly youre going to a famous blogger if you are not already Cheers

Excellent blog here Also your website loads up very fast What web host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

I just wanted to drop by and say how much I appreciate your blog. Your writing style is both engaging and informative, making it a pleasure to read. Looking forward to your future posts!

Your blog is a constant source of inspiration for me. Your passion for your subject matter is palpable, and it’s clear that you pour your heart and soul into every post. Keep up the incredible work!

Thank you for the auspicious writeup It in fact was a amusement account it Look advanced to far added agreeable from you However how can we communicate

My brother suggested I might like this blog He was totally right This post actually made my day You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this info Thanks

Your ability to distill complex concepts into digestible nuggets of wisdom is truly remarkable. I always come away from your blog feeling enlightened and inspired. Keep up the phenomenal work!

Chora Church tour Everything was well-explained and interesting. https://ativisautosales.com/?p=1032

Your blog is a constant source of inspiration for me. Your passion for your subject matter is palpable, and it’s clear that you pour your heart and soul into every post. Keep up the incredible work!

I have been surfing online more than 3 hours today yet I never found any interesting article like yours It is pretty worth enough for me In my opinion if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did the web will be much more useful than ever before

Your blog has quickly become my go-to source for reliable information and thought-provoking commentary. I’m constantly recommending it to friends and colleagues. Keep up the excellent work!

I simply could not go away your web site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard info a person supply on your guests Is going to be back incessantly to investigate crosscheck new posts

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here The sketch is attractive your authored material stylish nonetheless you command get got an impatience over that you wish be delivering the following unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike

helloI like your writing very so much proportion we keep up a correspondence extra approximately your post on AOL I need an expert in this space to unravel my problem May be that is you Taking a look forward to see you

Hi my family member I want to say that this post is awesome nice written and come with approximately all significant infos I would like to peer extra posts like this

Thank you for the auspicious writeup It in fact was a amusement account it Look advanced to far added agreeable from you However how can we communicate

Aydın Haber | Aydın Havadisleriaydın havadis haber, aydın haber, aydın haberleri, aydin haber

Kayışdağı su kaçak tespiti Ekip işini severek yapıyor, bu belli. Teşekkürler! https://camlive.ovh/read-blog/17073

Turkish street food tour Istanbul is now one of my favorite cities thanks to this tour. https://thnexapoint.com/?p=1121

At Bitcoin Invest, traders with over 10 years of experience provide stability and profitability.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So good to search out someone with some authentic thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for beginning this up. this website is something that’s wanted on the web, someone with a bit of originality. useful job for bringing something new to the internet!

Hüseyinli su kaçak tespiti Ekibin kullandığı termal kameralar sayesinde sorunum çözüldü. https://techfestcitp.com/read-blog/12850

Any high-tension wires around?

Do you allow site inspection?

I’m looking for something like this.

What happens if I change my mind after payment?

Is there a Certificate of Occupancy or Governor’s Consent?

How far is it from the expressway?

Menurutku ini menarik banget, bisa jadi referensi buat banyak orang. Sukses terus ke depannya!

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at one place

Rainx Drive is the Best Cloud Storage Platform

Your blog is a treasure trove of valuable insights and thought-provoking commentary. Your dedication to your craft is evident in every word you write. Keep up the fantastic work!

https://shovelhunter.com/index.php/shop/

My brother recommended I might like this web site He was totally right This post actually made my day You cannt imagine just how much time I had spent for this information Thanks

https://shovelhunter.com/index.php/product/1948-panhead-for-sale/

Nice blog here Also your site loads up very fast What host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Thank you for the clear roadmap — it makes the process less intimidating.

في عالم الضيافة العربية، لا شيء يضاهي روعة تمور طبيعية 100٪، تمر شيشي فاخر، تمور طازجة فاخرة، تمور المناسبات الخاصة، تمر شيشي جامبو، أسعار التمور في السعودية، كرتون تمر شيشي جامبو، تمر النخبة للضيافة الراقية، رز حساوي فاخر، خليط مُخصص لصناعة كيكة التمر، تمور رمضان الفاخرة، عصيدة حساوية جاهزة. تُعد هذه المنتجات رمزاً للجودة والفخامة، حيث يتم اختيار أجود أنواع التمور والمنتجات الحساوية بعناية فائقة. من المعروف أن التمور ليست مجرد طعام، بل هي إرث ثقافي يعكس كرم الضيافة العربية وأصالة المذاق الفريد. كما أن الطلب المتزايد على هذه المنتجات جعلها خياراً مثالياً للمناسبات الخاصة والاحتفالات، لتكون دائماً حاضرة على الموائد.

This topic has become increasingly relevant among travelers looking for meaningful and unconventional experiences. From personal adventures and numerous travel blogs, it’s clear that more people are shifting toward discovering hidden gems, immersing in local cultures, and minimizing environmental impact. Exploring new places isn’t just about sightseeing anymore—it’s about forming connections, gaining new perspectives, and sometimes, rediscovering oneself. Whether it’s walking through a quiet village, joining a traditional cooking class, or simply watching wildlife in its natural habitat, these moments are what truly enrich the travel experience. With the growing awareness around sustainability and authentic experiences, it’s time we look beyond the mainstream and embrace journeys that are both enriching and responsible. For anyone planning their next trip, considering these aspects can make a world of difference.

Howdy! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could locate a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

Teknoloji Kıbrıs Teknoloji Kıbrıs, Kıbrıs teknoloji, teknolojikibris, elektronik eşyalar, Kıbrıs ucuz ev eşyası, teknolojik aksesuar kıbrıs

becem travel | Kıbrıs araç transfer Kıbrıs araç kiralama , Kıbrıs vip araç , Kıbrıs araç transfer , Kıbrıs güvenli ulaşım

Your blog is a breath of fresh air in the often mundane world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging writing style never fail to leave a lasting impression. Thank you for sharing your insights with us.

Your tone is friendly and informative — made for an enjoyable read.

This blog is a gem. AI is changing how we work every day, and prompt tools are underrated.

Thanks for sharing superb informations. Your website is so cool. I am impressed by the details that you¦ve on this web site. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this web page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found just the info I already searched everywhere and simply couldn’t come across. What a great site.

This article is such a breath of fresh air… or perhaps a gentle touch of a conservators hand adjusting a camera? Either way, its refreshing to see care extended to the tangible echoes of history. Who knew preserving ancient manuscripts was so… tactile? Its like the digital ages answer to a good old-fashioned massage, but for books! And the comments section? A delightful array of Timbuktu-themed tourism tips and the eternal quest for the perfect online gambling strategy. Truly, a microcosm of human experience.ai remove watermarks

Rakiplerine göre daha güvenilir bir deneyim sunuyor.

Para çekim işlemleri sorunsuz ve hızlı.

This Timbuktu piece is fascinating! Its like they took the intimate care we give our own bodies and applied it to ancient manuscripts. Who knew preserving history felt so much like giving a gentle massage to a dusty old book? The comparison is brilliant, though I imagine the paperwork is exponentially more complex! Kudos to these guardians of culture, turning quiet heroism into lasting memory – and maybe a few fascinating digitized collections along the way. Now, wheres my blue cloth?basketball stars unblocked

I appreciate the step-by-step instructions. They made implementation easy.

Short but powerful — great advice presented clearly.

Teknoloji Kıbrıs Teknoloji Kıbrıs, Kıbrıs teknoloji, teknolojikibris, elektronik eşyalar, Kıbrıs ucuz ev eşyası, teknolojik aksesuar kıbrıs

Dxd Global | Development dxd global, global dxd, deluxe bilisim, deluxe global, IT solutions, web developer, worpress global, wordpress setup

Thank you — the troubleshooting tips saved me from major issues.

becem travel | Kıbrıs araç transfer Kıbrıs araç kiralama , Kıbrıs vip araç , Kıbrıs araç transfer , Kıbrıs güvenli ulaşım

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites

Very helpful explanation — I learned several useful techniques.

Bosphorus cruise Plenty of photo stops, no rushing at all. https://iramawear.com/?p=5570

This is really interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks!

I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I added it to my bookmark site list and will

I’m often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your web site and maintain checking for brand spanking new information.

Antalya tours Turkey Outstanding Turkey vacation packages. Religious sites were respectfully presented and deeply moving. http://blogginmamas.com/?p=19868

Turkey wine tasting tours James T. – İngiltere https://cxda.ae/?p=2872

Turkey travel itinerary Wonderful Turkey tours! The sunset at Temple of Apollo in Side was the most romantic moment ever. https://abknives.shop/?p=4483

Short but powerful — great advice presented clearly.

Please write more about the challenges you mentioned — curious for solutions.

Escort Dating for Click: https://helboy.yenibayanlar.com/kategori/mus-escort/malazgirt-escort/

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!

You’re so awesome! I don’t believe I have read a single thing like that before. So great to find someone with some original thoughts on this topic. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This website is something that is needed on the internet, someone with a little originality!

Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.

I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I added it to my bookmark site list and will

This is really interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks!

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites

Pretty! This has been a really wonderful post. Many thanks for providing these details.

I really like reading through a post that can make men and women think. Also, thank you for allowing me to comment!

I like the efforts you have put in this, regards for all the great content.

Pamukkale tours Turkey Samantha B. – Gürcistan https://anandinstitutebhopal.com/?p=62840

Teknoloji Kıbrıs Teknoloji Kıbrıs, Kıbrıs teknoloji, teknolojikibris, elektronik eşyalar, Kıbrıs ucuz ev eşyası, teknolojik aksesuar kıbrıs

Dxd Global | Development dxd global, global dxd, deluxe bilisim, deluxe global, IT solutions, web developer, worpress global, wordpress setup

becem travel | Kıbrıs araç transfer Kıbrıs araç kiralama , Kıbrıs vip araç , Kıbrıs araç transfer , Kıbrıs güvenli ulaşım

Discover Ij canon start to easily set up your Canon printer. Follow step-by-step instructions for installation, wireless connection, and driver setup.

Fetih su kaçak tespiti Su kaçağı, sessiz ve görünmez bir tahribat etkeni olabilir. https://share.google/PU5VPospAdoIsYzq3

İstanbul gizli su kaçağı tespiti Pratik Çözüm: Tesisat sorunlarına pratik çözümler sundular. https://share.google/PU5VPospAdoIsYzq3

Ich habe kürzlich den Münzankauf & Münzverkauf ausprobiert und war sehr zufrieden mit dem gesamten Ablauf. Besonders beeindruckt hat mich die Schmuck aus Erbschaften und Nachlässen und die freundliche, kompetente Beratung im Medienbekannter Juwelier Deutschland. Alles verlief transparent, professionell und zu einem fairen Preis. Ich empfehle diesen Service jedem weiter, der Wert auf Qualität und Vertrauen legt.

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

This was beautiful Admin. Thank you for your reflections.

There is definately a lot to find out about this subject. I like all the points you made

Awesome! Its genuinely remarkable post, I have got much clear idea regarding from this post

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at one place

I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I added it to my bookmark site list and will

naturally like your web site however you need to take a look at the spelling on several of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth on the other hand I will surely come again again.

Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.

**mindvault**

Mind Vault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking

Turkey travel itinerary Turkey vacation packages include everything needed for perfect holiday. The Black Sea region was surprisingly beautiful. https://mulrosas.com//?p=14055

**mindvault**

mindvault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

I do not even understand how I ended up here, but I assumed this publish used to be great

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles

Great information shared.. really enjoyed reading this post thank you author for sharing this post .. appreciated

There is definately a lot to find out about this subject. I like all the points you made

This blog post is like that one friend who always sends you those long, informative links you ignore. You know, the kind thats like, Check out this stuff about Mali manuscripts! And youre like, Cool Mali, gonna go there now! Then you realize youve been reading about Mali for five minutes and you still have no idea what the manuscripts actually look like. Its like trying to read a menu in a language you dont speak, except the language is history and the food is information. You get full but still hungry for more, and youre not even sure if it was a good meal.ai watermark remover free

Turkey historical tours Turkey vacation packages exceeded all expectations. Professional organization and authentic cultural experiences. http://www.tecnoac.com/?p=56090

Learning more about Infant Development allows families to create an environment that supports learning, play, and emotional development. This connection between family and child shapes a happier and healthier future. Learning more about Infant Development allows families to create an environment that supports learning, play, and emotional development. This connection between family and child shapes a happier and healthier future.

Thanks for taking the time to break this down step-by-step.

This is now one of my favorite blog posts on this subject.

I love how practical and realistic your tips are.

It’s great to see someone explain this so clearly.

Your tips are practical and easy to apply. Thanks a lot!

There is definately a lot to find out about this subject. I like all the points you made

I wasn’t sure what to expect at first, but this turned out to be surprisingly useful. Thanks for taking the time to put this together.

I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I added it to my bookmark site list and will

I’m often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your web site and maintain checking for brand spanking new information.

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing

Your content never disappoints. Keep up the great work!

naturally like your web site however you need to take a look at the spelling on several of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth on the other hand I will surely come again again.

I really appreciate content like this—it’s clear, informative, and actually helpful. Definitely worth reading!

Hi there to all, for the reason that I am genuinely keen of reading this website’s post to be updated on a regular basis. It carries pleasant stuff.

I do not even understand how I ended up here, but I assumed this publish used to be great

Your writing style makes complex ideas so easy to digest.

This made me rethink some of my assumptions. Really valuable post.

What an engaging read! You kept me hooked from start to finish.

This was easy to follow, even for someone new like me.

I wish I had read this sooner!

This is one of the best explanations I’ve read on this topic.

I love how clearly you explained everything. Thanks for this.

Side tours Turkey Best Turkey tours for history buffs! Every site had layers of civilizations to explore and understand. https://abknives.shop/?p=4483

This is one of the best explanations I’ve read on this topic.

في عالم الضيافة العربية، لا شيء يضاهي روعة تمر النخبة للضيافة الراقية، تمر بضمان الجودة، تمر شيشي ملكي، تمور رمضان الفاخرة، alhasa، تمور بدون مواد حافظة، تمور طازجة فاخرة، تمر رزيز، طلب تمور بالجملة، الذهب الأحمر الحساوي، هدايا تمور فاخرة للعائلات. تُعد هذه المنتجات رمزاً للجودة والفخامة، حيث يتم اختيار أجود أنواع التمور والمنتجات الحساوية بعناية فائقة. من المعروف أن التمور ليست مجرد طعام، بل هي إرث ثقافي يعكس كرم الضيافة العربية وأصالة المذاق الفريد. كما أن الطلب المتزايد على هذه المنتجات جعلها خياراً مثالياً للمناسبات الخاصة والاحتفالات، لتكون دائماً حاضرة على الموائد. إن الحسا يعكس تميز الإنتاج المحلي وجودته.

This topic has become increasingly relevant among travelers looking for meaningful and unconventional experiences. From personal adventures and numerous travel blogs, it’s clear that more people are shifting toward discovering hidden gems, immersing in local cultures, and minimizing environmental impact. Exploring new places isn’t just about sightseeing anymore—it’s about forming connections, gaining new perspectives, and sometimes, rediscovering oneself. Whether it’s walking through a quiet village, joining a traditional cooking class, or simply watching wildlife in its natural habitat, these moments are what truly enrich the travel experience. With the growing awareness around sustainability and authentic experiences, it’s time we look beyond the mainstream and embrace journeys that are both enriching and responsible. For anyone planning their next trip, considering these aspects can make a world of difference.

Your content always adds value to my day.

There is definately a lot to find out about this subject. I like all the points you made

You’re so awesome! I don’t believe I have read a single thing like that before. So great to find someone with some original thoughts on this topic. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This website is something that is needed on the internet, someone with a little originality!

Great information shared.. really enjoyed reading this post thank you author for sharing this post .. appreciated

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at one place

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

I really like reading through a post that can make men and women think. Also, thank you for allowing me to comment!

Pretty! This has been a really wonderful post. Many thanks for providing these details.

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles

There is definately a lot to find out about this subject. I like all the points you made

For the reason that the admin of this site is working, no uncertainty very quickly it will be renowned, due to its quality contents.

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites

Side tours Turkey Benjamin L. – Tayvan https://belasartchive.shop/?p=3433

affordable Turkey tours Oliver D. – Afganistan https://www.iranto.ir/?p=141836

Turkey tours Victoria L. – Azerbaycan https://fertilis.io/?p=16270

The perfect escape from a busy world. A massage is your little slice of heaven.

Consider the therapeutic benefits of a massage. It’s a proven method for relief.

Trust me on this one. A massage is the best thing you can do for yourself.

You clearly know your stuff. Great job on this article.

Such a refreshing take on a common topic.

I like how you kept it informative without being too technical.

This content is gold. Thank you so much!

This post cleared up so many questions for me.

I learned something new today. Appreciate your work!

**glpro**

glpro is a natural dietary supplement designed to promote balanced blood sugar levels and curb sugar cravings.

This post gave me a new perspective I hadn’t considered.

You’re doing a fantastic job with this blog.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge. This added a lot of value to my day.

**sugarmute**

sugarmute is a science-guided nutritional supplement created to help maintain balanced blood sugar while supporting steady energy and mental clarity.

Thanks for making this so reader-friendly.

I’ve bookmarked this post for future reference. Thanks again!

I wasn’t expecting to learn so much from this post!

This post gave me a new perspective I hadn’t considered.

**vittaburn**

vittaburn is a liquid dietary supplement formulated to support healthy weight reduction by increasing metabolic rate, reducing hunger, and promoting fat loss.

This post cleared up so many questions for me.

I agree with your point of view and found this very insightful.

**synaptigen**

synaptigen is a next-generation brain support supplement that blends natural nootropics, adaptogens

**glucore**

glucore is a nutritional supplement that is given to patients daily to assist in maintaining healthy blood sugar and metabolic rates.

I’ll definitely come back and read more of your content.

I appreciate the real-life examples you added. They made it relatable.

This was so insightful. I took notes while reading!

This gave me a whole new perspective on something I thought I already understood. Great explanation and flow!

I appreciate the honesty and openness in your writing.

**prodentim**

prodentim an advanced probiotic formulation designed to support exceptional oral hygiene while fortifying teeth and gums.

I agree with your point of view and found this very insightful.

**nitric boost**

nitric boost is a dietary formula crafted to enhance vitality and promote overall well-being.

Hi my loved one I wish to say that this post is amazing nice written and include approximately all vital infos Id like to peer more posts like this

You’re doing a fantastic job with this blog.

Thanks for making this easy to understand even without a background in it.

I feel more confident tackling this now, thanks to you.

Great points, well supported by facts and logic.

This was really well done. I can tell a lot of thought went into making it clear and user-friendly. Keep up the good work!

You’ve built a lot of trust through your consistency.

This gave me a whole new perspective on something I thought I already understood. Great explanation and flow!

This gave me a whole new perspective. Thanks for opening my eyes.

So simple, yet so impactful. Well written!

**wildgut**

wildgutis a precision-crafted nutritional blend designed to nurture your dog’s digestive tract.

You’re doing a fantastic job with this blog.

This article came at the perfect time for me.

What I really liked is how easy this was to follow. Even for someone who’s not super tech-savvy, it made perfect sense.

I like how you kept it informative without being too technical.

**sleeplean**

sleeplean is a US-trusted, naturally focused nighttime support formula that helps your body burn fat while you rest.

Very useful tips! I’m excited to implement them soon.

Thank you for putting this in a way that anyone can understand.

I appreciate your unique perspective on this.

The way you write feels personal and authentic.

Thank you for offering such practical guidance.

Great points, well supported by facts and logic.

I love how clearly you explained everything. Thanks for this.

This was easy to follow, even for someone new like me.

You’ve sparked my interest in this topic.

I like how you kept it informative without being too technical.

Such a thoughtful and well-researched piece. Thank you.

**mitolyn**

mitolyn a nature-inspired supplement crafted to elevate metabolic activity and support sustainable weight management.

**yusleep**

yusleep is a gentle, nano-enhanced nightly blend designed to help you drift off quickly, stay asleep longer, and wake feeling clear.

**zencortex**

zencortex contains only the natural ingredients that are effective in supporting incredible hearing naturally.

**breathe**

breathe is a plant-powered tincture crafted to promote lung performance and enhance your breathing quality.

**prostadine**

prostadine is a next-generation prostate support formula designed to help maintain, restore, and enhance optimal male prostate performance.

**pineal xt**

pinealxt is a revolutionary supplement that promotes proper pineal gland function and energy levels to support healthy body function.

**energeia**

energeia is the first and only recipe that targets the root cause of stubborn belly fat and Deadly visceral fat.

**prostabliss**

prostabliss is a carefully developed dietary formula aimed at nurturing prostate vitality and improving urinary comfort.

**boostaro**

boostaro is a specially crafted dietary supplement for men who want to elevate their overall health and vitality.

**potent stream**

potent stream is engineered to promote prostate well-being by counteracting the residue that can build up from hard-water minerals within the urinary tract.

You’ve built a lot of trust through your consistency.

This is one of the best explanations I’ve read on this topic.

Thank you for making this topic less intimidating.

This was a great reminder for me. Thanks for posting.

This is exactly the kind of content I’ve been searching for.

You explained it in such a relatable way. Well done!

Such a thoughtful and well-researched piece. Thank you.

Your advice is exactly what I needed right now.

You explained it in such a relatable way. Well done!

I’ve gained a much better understanding thanks to this post.

Thank you for making this topic less intimidating.

Such a refreshing take on a common topic.

This article came at the perfect time for me.

This gave me a whole new perspective. Thanks for opening my eyes.

Such a thoughtful and well-researched piece. Thank you.

I wasn’t expecting to learn so much from this post!

Thank you for sharing this! I really enjoyed reading your perspective.

You explained it in such a relatable way. Well done!

Great post! I’m going to share this with a friend.

Thanks for addressing this topic—it’s so important.

Very useful tips! I’m excited to implement them soon.

This content is gold. Thank you so much!

You write with so much clarity and confidence. Impressive!

I appreciate your unique perspective on this.

I love how clearly you explained everything. Thanks for this.

You always deliver high-quality information. Thanks again!

I really needed this today. Thank you for writing it.

I love how clearly you explained everything. Thanks for this.

You’ve done a great job with this. I ended up learning something new without even realizing it—very smooth writing!

So simple, yet so impactful. Well written!

You’ve done a great job with this. I ended up learning something new without even realizing it—very smooth writing!

Thanks for making this easy to understand even without a background in it.

Your breakdown of the topic is so well thought out.

I love how practical and realistic your tips are.

I really needed this today. Thank you for writing it.

I like how you kept it informative without being too technical.

Such a refreshing take on a common topic.

This gave me a lot to think about. Thanks for sharing.

Your content always adds value to my day.

What a great resource. I’ll be referring back to this often.

I learned something new today. Appreciate your work!

This gave me a lot to think about. Thanks for sharing.

I’ve read similar posts, but yours stood out for its clarity.

**hepatoburn**

hepatoburn is a premium nutritional formula designed to enhance liver function, boost metabolism, and support natural fat breakdown.

Very useful tips! I’m excited to implement them soon.

This post cleared up so many questions for me.

Thank you for offering such practical guidance.

Your breakdown of the topic is so well thought out.

**hepatoburn**

hepatoburn is a potent, plant-based formula created to promote optimal liver performance and naturally stimulate fat-burning mechanisms.

This topic is usually confusing, but you made it simple to understand.

Thank you for covering this so thoroughly. It helped me a lot.

I’ve read similar posts, but yours stood out for its clarity.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge. This added a lot of value to my day.

This is exactly the kind of content I’ve been searching for.

This topic really needed to be talked about. Thank you.

I always look forward to your posts. Keep it coming!

Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.

So simple, yet so impactful. Well written!

I really like reading through a post that can make men and women think. Also, thank you for allowing me to comment!

Thanks for sharing your knowledge. This added a lot of value to my day.

Such a refreshing take on a common topic.

I love how clearly you explained everything. Thanks for this.

Such a simple yet powerful message. Thanks for this.

This article came at the perfect time for me.

Such a refreshing take on a common topic.

Thanks for making this so reader-friendly.

I appreciate the depth and clarity of this post.

Your content never disappoints. Keep up the great work!

This is one of the best explanations I’ve read on this topic.

I feel more confident tackling this now, thanks to you.

The way you write feels personal and authentic.

What a helpful and well-structured post. Thanks a lot!

Your content always adds value to my day.

Your tips are practical and easy to apply. Thanks a lot!

What a great resource. I’ll be referring back to this often.

Such a simple yet powerful message. Thanks for this.

I’m definitely going to apply what I’ve learned here.

Great article! I’ll definitely come back for more posts like this.

I love how practical and realistic your tips are.

**flow force max**

flow force max delivers a forward-thinking, plant-focused way to support prostate health—while also helping maintain everyday energy, libido, and overall vitality.

**neuro genica**

neuro genica is a dietary supplement formulated to support nerve health and ease discomfort associated with neuropathy.

**cellufend**

cellufend is a natural supplement developed to support balanced blood sugar levels through a blend of botanical extracts and essential nutrients.

**prodentim**

prodentim is a forward-thinking oral wellness blend crafted to nurture and maintain a balanced mouth microbiome.

JAV HD Không Che, Tuyển tập phim jav hd đụ gái xinh không che,

**revitag**

revitag is a daily skin-support formula created to promote a healthy complexion and visibly diminish the appearance of skin tags.

‘I’ button on the controls open a paytable where you can check out symbol values at the current skate, plus info on the extra features. Big Bass Bonanza – Hold & Spinner has 10 paylines and the you need matched symbol across a line from the left to win a prize. The float pays the most, at 200x the stake for a full run of 5. Mystery-themed slot machines have always attracted the special attention of gamers, they arent exactly cutting edge. If no code is listed, big bass bonanza game available in demo mode its rare that they will actually serve you with a complete ban. At these tables, players can play their favorite games on the go using their smartphones and tablets. Big bass bonanza casino review these mobile blackjack applications can be accessed from anywhere inside of Minnesota as long as your iPhone, you win the progressive jackpot. It also regularly creates new games that are specifically designed for mobile, content marketing services to top brands who want quality bingo game products for their players.

http://travelgatesl.com/?p=18223

Big Bass Bonanza:Pros You can email the site owner to let them know you were blocked. Please include what you were doing when this page came up and the Cloudflare Ray ID found at the bottom of this page. Big Bass Bonanza slot is a nature-themed slot game that anyone who loves fishing or nature will enjoy playing. It features a fisherman exploring the water to catch beautiful bass fishes. The game’s visuals capture this just right, and the game’s symbols fit in perfectly too. Big Bass Bonanza’s symbols in decreasing order of payout value are a Bobber Float, Fishing Rod, Dragon Fly, Fishing Kit, Fish, and regular playing cards. You can email the site owner to let them know you were blocked. Please include what you were doing when this page came up and the Cloudflare Ray ID found at the bottom of this page.

Great points, well supported by facts and logic.

It’s refreshing to find something that feels honest and genuinely useful. Thanks for sharing your knowledge in such a clear way.

Thank you for covering this so thoroughly. It helped me a lot.

You’ve sparked my interest in this topic.

This is now one of my favorite blog posts on this subject.

I appreciate the real-life examples you added. They made it relatable.

I enjoyed every paragraph. Thank you for this.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge. This added a lot of value to my day.

Great article! I’ll definitely come back for more posts like this.

This content is really helpful, especially for beginners like me.

Thanks for making this so reader-friendly.

What an engaging read! You kept me hooked from start to finish.

Außerdem gibt es einen gut erreichbaren Kundenservice, den wir einmal via Live Chat kontaktiert haben. Hier wurde uns schnell und in deutscher Sprache weitergeholfen. Die gesamte Spielerschutzthematik das Platin Casino unserer Meinung nach sehr ernst. © Heike Bogenberger, autorenfotos Der Spieler schlüpft in die Rolle eines hoch entwickelten Androiden, aber gleichzeitig staunenden Kindes. Und das begegnet dem Geheimnis einer Welt, in der die Menschheit längst körperlich ausgestorben ist und als Geist in Maschinen weiterlebt. All das wirft natürlich Fragen nach der Art des Untergangs sowie der Unsterblichkeit auf, die schon uralte Mythologien und Religionen stellten, und die im so genannten Transhumanismus bis heute diskutiert werden. An diesen Themen hätte das Spiel scheitern können, wenn es sie einfach nur als Texte ausgelagert hätte.

https://www.gazeteposta.com/umfassende-analyse-des-amunra-casinos-fur-spieler-aus-deutschland/