Afro-Pessimism

and the Question of Biafran Nationalism

¬

By

Daniel Chukwuemeka

¬

¬

Saturday, March 9, 2019.

I

Perhaps the adoption of Afro-pessimism ‚Äď by intellectuals

– as a critical method in the evaluation of African nationalism, is to use it

as a theory to articulate alternative perspectives. On the one hand, those some considered as Black fundamentalists adopted

the term as a way to acknowledge the power, robustness and the radical nature

of the African imagination. Some proponents of Afro-pessimism have used it to

articulate the subject-position of abandonment, abjection, distancing, dread,

and doubt, in response to the enduring legacies of

colonialism. These include the view that dismantling white supremacy would mean demolishing much of

the social and political institutions of the modern world.

¬

Furthermore,

in international relations, Afro-pessimism is a

Western construct regarding the ongoing depiction of Africa and Africans in

Western media in terms of extreme poverty and backwardness by reflecting

Eurocentric images and rhetoric. As Noah Bassil noted in ‚ÄėThe Roots of

Afropessimism: The British Invention of the ‚ÄúDark Continent‚ÄĚ‚Äô, the

media tend to use such rhetoric to victimize and exoticize Africa for its ongoing

struggles with poverty and lack of modern development. The victimization

is then visible in the humanitarian and development projects, which

sometimes use the language of ‚Äėsaving‚Äô

African people from such humanitarian disasters. I argue that, drawing from the

Biafran quest for separate national entity from Nigeria as representative of

the first example of Afro-pessimism stated above, the second version of

Afro-pessimism which defends the merits of white supremacy can be a positive contrivance

atoning for its ugly past deeds if only it would‚ÄĒnot merely establish

humanitarian aids in Africa, but instead‚ÄĒsupport indigenous African nationhood,

since the bane of African politics and economy is ethnic conflicts in the

nation-states occasioned by colonialism.

¬

II

Can anything good ever come out of Africa? This is a

question which many, including Africans at home and abroad, grapple with

whenever they discuss the state of affairs in Africa. But Africa is not a

country. Despite the shared historical experience of its people, it is a vast

continent with countries of diverse cultures and development index. Where I

come from, Nigeria, for instance, afro-pessimism permeates the sentiments of

most middle and lower class citizens regarding a possible redemption of the

country from the shackles of underdevelopment.

I have lived all the 29 years of my life so far in

Nigeria, where I was born and raised. But I currently live in the UK as an

academic. Prior to this, I lived in Germany, where I worked as part of an

editorial team creating an Oxford English-Igbo bilingual dictionary. Even

before my first six months contract was extended by my employer in Germany,

friends and family in Nigeria and a few others in the West (but especially

those in Nigeria) had insisted, advised, and begged that I should ‚Äėfind a way‚Äô

to remain ‚Äėthere‚Äô (Germany) after the expiration of my contract. ‚ÄėFind yourself

a casual job, even if menial‚Äô, one of them opined, ‚Äėinstead of returning to

Nigeria’. This is apparently one of their subtle ways of expressing

hopelessness in the Nigerian system. But I am not ignorant of the sources of

their frustrations.

In early March, this year, I was introduced to

Afro-pessimism by the keynote speaker at a conference on ‚ÄėUrban Walking‚Äô which

I was attending at Friedrich-Schiller-University in the small German city of Jena. I had finished my

presentation on negotiating cultural memory through urban noise in Teju Cole’s

novel, Open City in which I, among

other submissions, asserted that New York City today was built and developed by

the ruins, blood and sweat of the black slaves. I remember this because while

he approached me after my presentation, the keynote speaker, David Kishik of

Emerson College, Boston, Massachusetts, had emphasized the need for my

theorizing on the concept of Blackness to consider a certain Afro-pessimist

angle, that is, (and I suppose that was what he meant because our meeting was

very short and interrupted by the conference proceedings) one that will take a

nuanced and ambivalent position toward the subject and therefore strike a

balance between emphasizing the historical trauma of slavery and colonialism

and a critique of problems of contemporary African governance. Later I would

find Manthia Diawara’s In Search of

Africa, Kwame Anthony Appiah’s In My

Father’s House, and Achille Mbembe’s On

the Postcolony as critical testaments buttressing this perspective.

Before being prompted by Professor Kishik to take a

critical stand on Afro-pessimism, my position had always been that it was a

dormant discourse that is at best a consequence of Eurocentrism: that notion

that Africans are incapable of self-rule and need to be saved from themselves,

at least for the sake of humanity, read as the white man’s burden. But while I

dismissed such stance, which proceeds from an obvious invalidation of the historical

relevance of the African experience, I am not unaware of the fact that

apologists of organized violence against colonized societies such as the German

philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, justify the state of things in

Africa by totally berating the continent in the most callous terms.

If Hegel’s position was obsolete, so to say, since it

was made in the beginning of the nineteenth century, today we can still find

Western writers and journalists who make pessimistic comments concerning

Africa‚Äôs future. (Wafulo Okumo, in ‚ÄėAfro-Pessimism and African Leadership‚Äô

reminds us that the futurist author, Paul Kennedy pronounced in 1983 that

Africa‚Äôs future was ‚Äėextraordinarily gloomy‚Äô; journalists such as Blaine

Harden, in ‚ÄėAfrica‚ÄĒDispatches from a Fragile Continent‚Äô, David Lamb, in The Africans, Keith Richburg, in Out of America, and Peter Marnham, in Dispatches from Africa, ‚Äėbrazenly

painted Africa in dreary terms: unbridled corruption, state brutality, severe

underdevelopment and general desolation‚Äô. Also Robert D. Kaplan, in ‚ÄėThe Coming

Anarchy‚Äô declared that Africa is ‚Äėat the edge of the abyss‚Äô; and in its June

16, 1997 issue devoted to the theme, ‚ÄėAfrica is Dying‚Äô, The New Republic contested that what is happening to Africa ‚Äėis

nothing less than Africa’s exit from international society’.)

However, even as some Africans have themselves become

afro-pessimists in the above guise of thought, not all western observers of

Africa have completely written it off as a hopeless case. Therefore, while

Michael Chege, an African scholar at the center for African Studies of the

University of Florida had predicted that Africa is the only region in the world

where poverty and political violence are likely to increase in the opening

years of the twenty-first century, and as the likes of Jean-Francois Bayart

(author of Criminalization of the State

in Africa) and Patrick Chabal (author of Africa Works: Disorders as Politician Instrument) incessantly make

reference to the distressed and dysfunctional state of affairs in Africa, the

Western journalist, Blaine Harden, proposes that Africa could possibly be

rescued under a special programme such as a Marshall Plan, though a scheme

which critics such as Henry Hazlitt (in his book, Will Dollars Save the World?) and Ludwig von Mises, and which also

the historical revisionist Walter LaFeber have largely and effortlessly proven

to have had insignificant contributions in the economic recovery of Western

Europe, and ultimately a scheme which is unacceptable to the proposal of this paper

in relation to the African situation.

¬

III

Outside the scope of academic theorizing, and

especially in the new media world of contemporary art, photography and news

reporting, Afro-pessimism is often blamed as the idea behind the performance of

Africa to the world in the form of what has come to be known as poverty-porn. Many

African scholars have condemned the lackluster and monotonous representation of

African realities in the media and art, especially by the West and a few other

African writers.

Africa has very serious leadership problems, which

have over time culminated in rendering it impoverished and underdeveloped. As

Teju Cole would say, ‚ÄėLagos is shit: people really suffer, so we are not going

to paint a picture that makes it look rosy. But, on the other hand, when you

acknowledge that Lagos is shit but it’s our Lagos, and we take care of each

other a little bit, that‚Äôs also largely a relief‚Äô. Then he added, ‚ÄėIf you do

something that has many layers and some people just have a tag-line to describe

it, then they are not talking about you. They are talking about themselves’.

The story of Africa has ‚Äėmany layers‚Äô and it will be quite preposterous for one

to reduce a whole continent to an obscure entity. I agree with Teju Cole that

such accounts of Africa are grossly uninformed and unbalanced, and seem to say

something about the gratuitous feeling which Frank B Wilderson says accompanies

the violence against the Black race, whose only request from humanity is for recognition

and incorporation.

The ambivalence of Afro-pessimism, even without its

theorizing aspects, does not condone undue sentimentalism. Providing only a

positive image of Africa to the world is not the forte of academics and leaders

of thought. Such is rather the calling of advertising agencies. The role of

intellectuals in this area is instead to fashion out a different environment

where a discourse on Africa devoid of representational prejudice would thrive.

This will therefore require a redefinition of the African epistemology on

Afro-pessimism in order to fashion out one that will, according to Enwezor

Okwui, be premised on ‚Äėthe recognition of the complexity of each situation,

seeing and writing about what is at hand in any given context as part of a

larger world and not merely as a series of disjointed, fragmentary narratives’.

There is need, therefore, for us to move away, as

proposed by Mohammed Ibrahim in a 2015 interview with France 24, from

Afro-pessimism and Afro-optimism‚ÄĒboth which are a general branding of Africa

sometimes as a basket case and other times as the new frontier of economic

development‚ÄĒto Afro-realism: the need to look at what is going on, the

realities on ground. Ibrahim pointed out how much a misnomer it is to stick one

label to a continent of 54 countries, noting that countries such as Mauritius,

Namibia, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and some other African countries are

moving forward. But he did not hesitate to also mention the systemic failure in

other African countries such as South Sudan, Libya, and Nigeria.

Mohammed Ibrahim’s realistic view of Africa comes with

one suggestion for an easier management and administration of African

countries: a more ‚Äėhomogenous population‚Äô in order to make governance easy, as

in the case of Namibia, since this will ensure a relaxation of political

tensions that are usually fuelled by religious and ethnic diversity and

competition.  I argue that Nigeria’s

large population and diversity, going by this index, does not contribute

positively to its governance and development.

¬

IV

In the spirit of specificity, Nigeria’s national

stories of debilitation can be addressed from the perspective of re-examination

of its national foundation. So instead of propagating Afro-pessimism (the subject-position of abandonment,

abjection, distancing, dread, and doubt in response to the massive, unending

consequences and historical upsets of

colonialism) or Afro-optimism (acknowledgement of the power and vivacity of the

pliability and radical imagination of Nigerians without addressing fundamental

national questions), we need a more viable middle ground, Afro-realism, one

that will draw the above elements of Afro-optimism in order to take to task the

reassessment of the factors that prompt its counterpart‚ÄĒAfro-pessimism. Thus

instead of providing Nigerians with humanitarian and development aids, (sometimes

using the language of ‚Äėsaving‚Äô

African people from humanitarian disasters‚ÄĒfinancial aids, such as from World

Bank and IMF, that African leaders end up looting, returning their nations’

developmental index to ground zero with increase in poverty and national

debts), the West can perhaps support indigenous African nationhood, since the

bane of African politics and economy is ethnic and religious conflicts in the

nation-states occasioned by colonialism. This instance of

Afro-realism that aims to dismantle the colonial

foundation of the Nigerian heterogeneous nationhood is exemplified in the

Biafran struggle for a separate nation state in Nigeria.

In Think Again, Marina Ottaway argues, with

very detailed and compelling points, that ethnic and cultural communities need

to be recognised as independent nation states, with her research interest in

politics of development centred in particular on Africa, the Balkans and the

Middle East. She identified the root cause of the underdevelopment of the many

failed states in the Global South when she declared that ‚ÄėMost of today‚Äôs

collapsed states, such as Somalia and Afghanistan, are a product of colonial

nation building. The greater the difference between the pre-colonial political

entities and what the colonial powers tried to impose, the higher the rate of

failure’ (17). Sadly, this is the case with Nigeria.

Biafran nationalism is

not going to be the first of its kind, as could be gleaned from the teachings

of Marina Ottaway:

Nationalism gave rise to most European countries that

exist today. The theory was that each nation, embodying a shared community of

culture and blood, was entitled to its own state… This brand of nationalism

led to the reunification of Italy in 1861 and Germany in 1871 and to the

break-up of Austria-Hungary in 1918. This process of nation building was

successful where governments were relatively capable, where powerful states

decided to make room for new entrants, and where the population of new states

was not deeply divided. (17)

The Nigerian

population today is deeply divided along ethnic lines. And this invariably

results in its government (which is helplessly incapable of running a state)

being ridiculously divisive in policy making and implementation.

Two means of nation

building, according to Ottaway, are through wars and intervention of the

international community:

The most successful nations, including the United

States and the countries of Europe, were built by war. These countries achieved

statehood because they developed the administrative capacity to mobilize

resources and to extract the revenue they needed to fight wars. Some countries

have been created not by their own efforts but by the decisions made by the

international community. The Balkans offer unfortunate examples of states

cobbled together from pieces of defunct empires. Many African countries exist

because colonial powers chose to grant them independence… Such countries have

been called quasi states‚ÄĒentities that exist legally because they are recognised

internationally but that hardly function as states in practice because they do

not have governments capable of controlling their territory. (18)

Nigeria is therefore

a quasi state. The Nigerian-Biafran civil war of 1967‚ÄĒ1970 failed to determine what

could have been an ideal Nigerian nation-state: one that could have existed as

today’s United Kingdom (with England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland as

its independent ethnic nationalities) or as a confederal state (such as we have

in Switzerland, Belgium, Canada, Serbia and Montenegro), or a dissolved state

(such as the case with the former USSR, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Sudan).

Having lost the opportunity to create a viable nation-state through the war,

Nigeria, with its fragile national unity that has never looked sustainable

since after the civil war, had to rely on the other form of nation building

which all colonised groups were bequeathed with. In fact, the fragile national

unity of Nigeria is sustained by the hegemony of British colonialism. And many

historians of the Biafran civil war have asserted that the Nigerian government

received military assistance in crushing the Biafran rebellion. But there can

hardly be a true peace among any group where justice is trampled on, for the pursuit

of peace in the absence of justice will always end in wasting human lives to protect

what must have been a fraudulent agreement.

Therefore, today’s

realities point to the fact that the British colonial design of a one Nigeria

is a colossal failure. Afro-realists must look towards questioning that

colonial foundation as the starting point of any feasible form of nation

building. Because the defeat in the war did not succeed in quenching the Igbo

nationalism and quest for a separate ethnic nationality, neither was it capable

of truly uniting Nigeria towards a common national consciousness and identity

for growth and development.

¬

V

It usually amuses me each

time a young Nigerian argues that it is intellectual laziness to finger the

British colonialism as the plague currently holding Nigeria down. I have always

maintained that such dismissive point of view is an ignorant and shallow

articulation of the nuances of the conundrum that is Nigeria, because I see

clearly how it fails to acknowledge the intellectual dishonesty and

irresponsibility in its rather romantic, disoriented claims. For me, what is

actually an exercise in intellectual laziness is the tendency to outright dismiss

the creation of Nigeria itself, the aims and objectives around it, by the

British, as insignificant in the discourse of the trouble with present day

Nigeria.

Nigeria is like a

house with a very faulty foundation. It will never withstand soil vibration from

political seismic activity. The founders of Nigeria (not Ahmadu Bello and

Nnamdi Azikiwe or Obafemi Awolowo, please. We need to stop indulging in

historical ignorance and self-deceit.), the British colonial administrators,

neglected the breaks in seams among the ethnic panels that make up the entity,

and thus disregarded the need to lay a very strong foundation with an enduring

identity for what Nigeria is and for what it means to be a Nigerian. The early

post-independence Nigerian leaders mentioned above, on the other hand, failed

to go back to the historical and philosophical and even anthropological

laboratory to test the factors needed to draw up concrete and tenacious

principles of what consists a Nigerian identity in order to solidify the faulty

foundation they were already left with by the British. They failed to see the

necessity to‚ÄĒsince they decided to accept the new artificially contrived nation-state

in the late 50s‚ÄĒforge a binding force, a national ideal to live and die for,

and a creed to abide by, for a strong cohesion capable of erasing doubts and

suspicion among the ethnic groups, for an easy economic growth and development,

peace and progress.

I may be too blunt in

declaring that those who we refer to as the Nigerian founding fathers,

mentioned above, were too laid back in profiling and redefining the young

nation handed over to them (in the guise of ‚Äėindependence‚Äô), but I will

unapologetically insist that the British colonial legacy of a one Nigeria is

what is stagnating the country till today. So when I claim that colonialism is

Nigeria’s chief problem, and one mentions other colonised countries who are progressing

today, I would like to invite them to desist from such intellectual laziness by

going further in details to analyse the local peculiarities of the nations being

compared.

Homogeneity will

greatly favour many groups of people that make up Nigeria, because it ensures

reduction‚ÄĒor even a gradual process that can lead to a possible non existence‚ÄĒof

ethno-religious conflicts and other generic clashes of interest. If this is not

realisable as circumstances might show, only a return to regional government

will salvage Nigeria today and set it up for a reversal of the British colonial

fraudulent foundation it has inherited.

We will therefore

continue looking forward to a day Nigeria will have, in large numbers, leaders

who will be fed up with the cosmetic surgery that is the country’s current administration.

Leaders with vision, who will think long term and therefore support and vote

for regional government. Until then, we can only just be MANAGING (in) Nigeria.

The Afro-pessimists

who seem to specialise in doling out financial aids to the corrupt Nigerian

leaders and the Afro-optimists who still have faith in the Nigerian human

capital should, if at all they are sincere enough, lend their voice in the call

for a referendum to be recognised and held by the Nigerian government to enable

the country’s different ethnic nationalities determine whether to accept or opt

out of the Nigerian project or remain a part of the union wielding a high level

of regional autonomy.¬

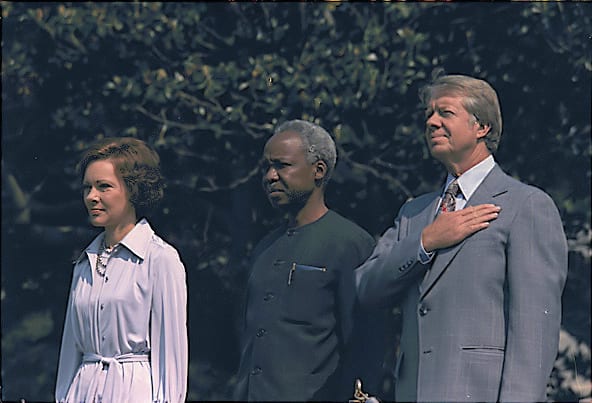

Main Picture: The city of Onitsha, Eastern Nigeria. Image: courtesy of Wikipedia –¬†By Nwabu2010 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46343581¬†This article was originally presented as an

academic paper at the ‚ÄėNations and Nationalisms: Theories, Practices and

Methods‚Äô International Postgraduate Conference, Loughborough University, UK.¬

Daniel Chukwuemeka is a PhD candidate at the

University of Bristol. His thesis links e-fraud economy with colonial and

postcolonial economics using literary and cultural representations of the

subject in contemporary Nigerian texts. He lives in Bristol.

Afro-Pessimism and the Question of Biafran Nationalism

No Comments currently posted | Add Comment

Comment on this Article

Your Name

Please provide your name

Your Comment

//set data for hoidden fields

//transfer();

var viewMode = 1 ;

//============================================================================

//HTML Editor Scripts follow

//============================================================================

function exCom(target,CommandID,status,value)

{

document.getElementById(target).focus();

document.execCommand(CommandID,status,value);

}

function transfer()

{

var HTMLcnt = document.getElementById(“ctl00_MainContent_txtComment_msgDiv1”).innerHTML;

var cnt = document.getElementById(“ctl00_MainContent_txtComment_msgDiv1”).innerText;

var HTMLtarget = document.getElementById(“ctl00_MainContent_txtComment_HTMLtxtMsg”)

var target = document.getElementById(“ctl00_MainContent_txtComment_txtMsg”)

HTMLtarget.value = HTMLcnt;

target.value = cnt;

}

function hidePDIECLayers(f,p)

{

//e.style.display = ‘none’

f.style.display = ‘none’

p.style.display = ‘none’

}

function toggle(e)

{

if (e.style.display == “none”)

{

e.style.display = “”;

}

else

{

e.style.display = “none”;

}

}

function ToggleView()

{

var msgDiv = document.getElementById(“ctl00_MainContent_txtComment_msgDiv1″);

if(viewMode == 1)

{

iHTML = msgDiv.innerHTML;

msgDiv.innerText = iHTML;

//alert(viewMode);

// Hide all controls

Buttons.style.display = ‘none’;

//selFont.style.display = ‘none’;

//selSize.style.display = ‘none’;

msgDiv.focus();

viewMode = 2; // Code

}

else

{

iText = msgDiv.innerText;

msgDiv.innerHTML = iText;

// Show all controls

Buttons.style.display = ‘inline’;

//selFont.style.display = ‘inline’;

//selSize.style.display = ‘inline’;

msgDiv.focus();

viewMode = 1; // WYSIWYG

}

}

function selOn(ctrl)

{

ctrl.style.borderColor = ‘#000000’;

ctrl.style.backgroundColor = ‘#ffffcc’;

ctrl.style.cursor = ‘hand’;

}

function selOff(ctrl)

{

ctrl.style.borderColor = ‘#9BC1DF’;

ctrl.style.backgroundColor = ”;

}

function selDown(ctrl)

{

ctrl.style.backgroundColor = ‘#8492B5’;

}

function selUp(ctrl)

{

ctrl.style.backgroundColor = ‘#B5BED6’;

}

¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬†¬

Size 1

Size 2

Size 3

Size 4

Size 5

Size 6

Size 7

//give focus to the msgdiv… always otherwise save button will not save content.

var mDiv = document.getElementById(“ctl00_MainContent_txtComment_msgDiv1”);

try

{ mDiv.focus();}

catch(e)

{

//alert(‘Invisible’)

}

//if ( <> ‘none’)

//

¬† Send to a friend ¬†| ¬

View/Hide Comments (0) ¬† | ¬