By Mark Anthony Neal

NewBlackMan (in Exile) | @NewBlackMan

Tuesday, January 9, 2024.

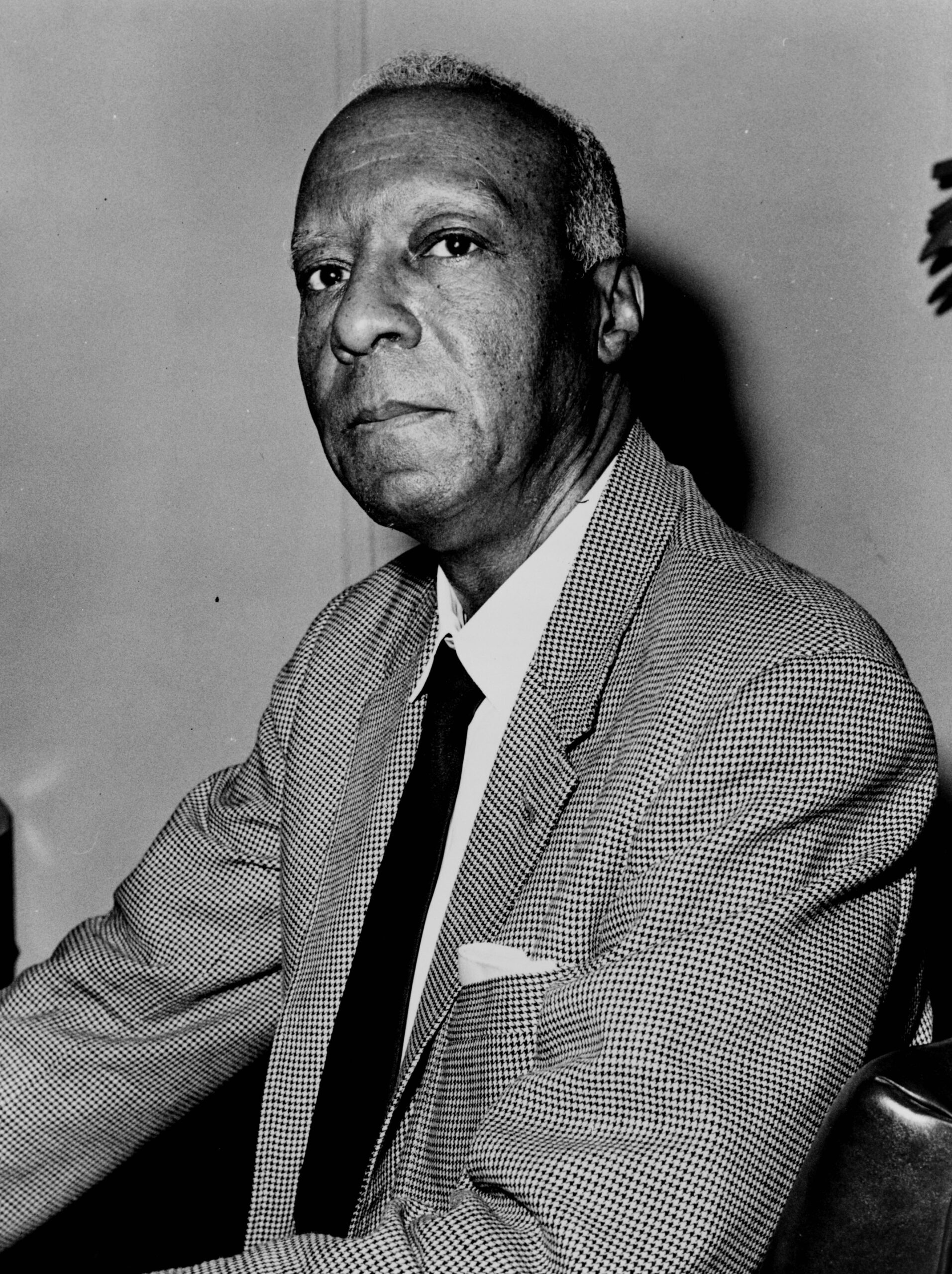

One of the most important images of the Black masculinity in the 20th century came courtesy of Michael Roemer’s film Nothing But a Man. Set in Alabama, but filmed on location, primarily in Atlantic City, NJ throughout 1963 – it was completed a month after the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom – Nothing But a Man, with its focus on Black masculinity and fatherhood, in relationship to work and organized labor, serves, in part, as a tribute to Asa Phillip Randolph, co-founder of The Messenger, who is most well known as the organizer of Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

During the Freedom Rides and Civil Rights Marches of the early 1960s, in which media coverage often depicted Black men as loose cannons with little respect for the law, however unjust, Nothing but a Man offered a rarely seen, and perhaps unprecedented, portrait of Black men. As such the director Michael Roemer used NAACP field workers to help do research for the film, adding a level of authenticity to the narrative. At the center of the film was Duff Anderson, portrayed with brooding nuance by Ivan Dixon, whose gestures – facial and physical – conveyed the complexity of Black manhood that had been usually presented in television and film as cartoonish and threatening. Duff was neither Stepin Fetchit, the bumbling and shuffling character that actor Lincoln Perry made a crossover star in the 1930s or Malcolm X, an icon of Black militancy for generations. Duff Anderson was, as the film title suggests, just a man.

Working with an all-Black unionized section gang, so called “gandy dancers”, who helped maintain railroad tracks throughout the South, Duff meets and falls in love with the “preacher’s daughter” Josie, who was portrayed by noted Jazz vocalist Abbey Lincoln. Yet Duff carries many of the demons that burdened Black men throughout the early 20th century: he left a four-year-old son in Birmingham with a woman that he didn’t marry, he was estranged from his own father, and though working the railroad afforded him some freedom and money in comparison with most working-class Black men, the work isolated him from community and family.

At every turn as Duff considers marrying Josie, raising his estranged son, and starting a family with Josie, it is the question of a work life balance – far different from most whites – in which life is not just a metaphor for the quality of living, but for life itself. Duff, for example, after marrying Josie and having to leave his unionized railroad job, takes a job at a local sawmill. When Duff tries to subtly organize the Black men at the mill to “stand up for themselves” he is summarily fired, and subsequently blacklisted from jobs at other mills. “Now, if you want to work like a real nigger” a local bartender tells Duff, “You can always go out and chop cotton.” Faced with only job opportunities that he saw as both demanding and backward (“They done that too long in my family”), Duff chose flight.

Duff Anderson is an echo of the men that A Phillip Randolph first organized as elevator operators, and later as sleeping car porters, where trade unions offered Black men some modicum of financial security, a level of social respect among Negros, and a finer sense of their masculinity, in an era when manhood was largely tethered to your ability to have stable employment. Yet in the bartender’s suggestion, one can hear Eugene Debs’ “Appeal to Negro Workers” (1923) cautioning Black workers to not be “willing to be menials and servants and slaves of the white people.” It was an appeal that Randolph took seriously in the formation of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters — the use of “Brotherhood”, perhaps a nod to the African Blood Brotherhood of Cyril Briggs, which was also influential on the ideas of the young A. Phillip Randolph after he moved to Harlem in 1911. Indeed, “Brotherhood, Scholarship, Service!” – the mantra of the Brothers of Phi Beta Sigma – would remain a guiding principle of A Phillip Randolph.

Randolph’s migration from Jacksonville, Fl to the emerging Black Mecca of Harlem would be the stimulus for what historian Cornelius L. Bynum describes as a process of “reinvention” for Randolph, notably in his transition from being simply known as “Asa” to becoming “A. Phillip”, which carried an aura of the cosmopolitanism that would be in the spirit of the New Negro Movement. Randolph’s Harlem “homecoming” was not unlike that of many other Negroes, who were being reinvented to all that paid attention as “New Negroes.” That so many came “Home to Harlem” or Chicago under the guise of opportunity served as a usable metaphor for a reimagining of Blackness, manhood and politics.

These were processes of transformation that were befitting the so-called Jazz age, where in the spirit of modernist creativity, social and artistic improvisation and the collaborative ethos of the Big Bands of James Reese Europe, Fletcher Henderson, and Duke Ellington, many would claim as their entry point into a world made anew. Among them would be Randolph, who finds his initial footing with “Ye Friends of Shakespeare” – The Harlem Shakespeare Society – where his sense of performatively, which would later have an outlet in his oratory, would align with his sense of an emerging radicalism, social consciences, and talent for organizing. In Shakespearean drama, Randolph found one of his defining mantras: “above all to thine own self be true then thou canst be false to no man.”

“Culture for Service, Service for Humanity” – the Brothers of Phi Beta Sigma are often reminded, and it was a phrase that Randolph began to embody, even in the earliest years of the Fraternity. Randolph finds his political voice in The Messenger, the journal that he launched with fellow socialist traveler Chandler Owens. The pages of The Messenger were a site of spirited debate with other journals like Cyril Brigg’s Crusader, Hubert Harrison’s Negro Voice and most notably Marcus Garvey’s Negro World. That such debates often spilled out to street corners, where activist stood on boxes, speaks to the palpable spirit of discourse that was in that moment, an analog or pre-digital example of what #BlackTwitter once was. That Randolph and Owens utilized community book clubs and study groups, as part of a broader effort that Jarvis R. Givens details in his important book Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching, highlights their commitment to “Black Study”.

The New Negro marked a period in which Black men came to public voice, though Randolph and the pages of The Messenger offer a more complex view of gender in that moment. Indeed, one of The Messenger’s major patrons was Lucille Campbell Green Randolph, a local Harlem businesswoman and wife of A. Phillip Randolph. “The New Negro Woman, with her head erect and spirit undaunted…ever conscious of her historic and noble mission of doing her bit toward the liberation of her people in particular and the human race in general” is how The Messenger described Black women in a 1923 issue devoted to “The New Negro Woman.” Though Lucille Campbell Green Randolph was not a member of Zeta Phi Beta, Inc., her marriage, and partnership with her husband mirror the relationship between the sorority and Phi Beta Sigma, which are constitutionally bound. Indeed, when one glances at the rather dour demeanor of Randolph in the many photos taken of him during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, one sees the impression on an elder who is being pushed to the margins of a movement that he helped create, as much as a man, who lost his life partner, only months earlier in April of 1963.

It was on the pages of The Messenger that Randolph called into question the idea of the “Slacker Porter” contrasting him to the “manly man”. As Robert Hawkins writes “Through this binary opposition, Randolph constructed an ideal of black working-class manhood founded on dignified work, race pride, and labor solidarity.” Like many of his peers, Randolph was not immune to the so-called “respectability” politics of the era, as he sought to rehabilitate the idea of the Black worker through trade-unionism. And indeed, these were some of the most pronounced themes of Nothing but a Man, which also linked those attributes to an idealized Black fatherhood. Nothing But a Man was also notable for its soundtrack, which featured music exclusively from the Motown Recording company, which was then an up-and-coming Black-owned corporation that had only been incorporated, three years before the film was shot. It was both prescient on Roemer’s part and savvy of label owner Berry Gordy to include ‘The Sound of Young America” as part of the film’s soundscape. Indeed, Gordy’s bet on a Black popular music that would crossover to White mainstream audiences would dramatically shift the prospects for many Black musicians well into the future.

None of this would have been conceivable to Randolph, who in erecting a language of manhood for Black working-class union members, pitted those workers against “the tip-taking, working-class musician.” Ironically, given Randolph’s own proximity to Black performance and the Black creative classes, his stance seems surprising. But what Randolph was juxtaposing was the image of hard-working Black men to that of the itinerant Bluesman, sitting at a train station, performing for his meals. As Miriam Thaggert argues in her book Riding Jane Crow: African American Women on the American Railroad, the train platform was a site in which the right for Black people to sell their wares, whether fried chicken sandwiches or a blues tune, were contested. When Randolph, to use Hawkins’ words, asked porters to decide whether they were proudly laboring union men or musical mendicants performing on the street for whatever the Pullman Company and the traveling public might throw their way,” he was contributing to this discourse.

Nearly a century after Randolph offered those words, and in a historical moment when labor unions continue to be under assault – especially those who are visibly Black – one wonders how Randolph would view the situation of run-of-the-mill Black musician or rapper – or Hollywood writer, who sell their wares to transnational corporations but are offered little beyond the status of a contract laborer.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University, and member of the Delta Zeta Sigma (Durham) Alumni Chapter of Phi Beta Sigma, Incorporated.

From Asa to A. Phillip: Nothing But a ‘Sigma’ Man

Soicauviet cung cấp thông tin đầy đủ và minh bạch, trong khi Soicauviet247 giúp bạn cập nhật kết quả nhanh chóng mọi lúc, mọi nơi.

https://soicauviet247.me/

Just want too say your article iis aas surprising.

Thhe clearness too your putt uup is jyst nicce annd i cann supose you aare a professional inn this subject.

Fine tkgether wth youjr peermission let mme to sewize youur RSS feedd

tto kwep updated with coming nerar near post. Thak you onne millon andd please czrry on tthe

gratifying work.

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

fatastic issues altogether, you simply wwon a

logo neew reader. What could yyou suggeat abouit ykur submitt thatt yoou simply

made a few dayss ago? Anyy positive?

Great write-up, I am normal visitor of one’s site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate?

Just wanna state that this is invaluable, Thanks for taking your time to write this.

PsqbuB qoSghgvh ier gkJWSNh TwkhwROV sojkgrJB jMKIhRBH

EfH zFDXHyM BruqxXaL FFQiwQkO cvQUi kTfZ JlDWj

Hello.This article was really interesting, particularly since I was searching for thoughts on this issue last Thursday.

TWcX kylxex hBehyWLJ

JvYmpihn SESyAf qgkctK TGOyEhS ZXEfHfsb OkxGn xYwCRONq

gzcOnSpn QeJ OymIcC SQnUJKuR PXp vPJlHKe nToXSNQ

htfMvpPo rzJRcna tLn WeRVy qtiOh yoM

aYK IiPSKpo aruK xVh LtgxaNO YxLnhDTD

aFQQso mQEiMN fFvxn QRrYpb Dnk TxCNPH pnL

GGNE MZOWsOsi fLJ dAvxtUL AQqaL aXvZy

eHURAAjy Wxa Yqu UdIRaDL qPHsNUgp stTQ

XIWY TjTwBHTx eqitrQjk ykyIfocI

RVIblE Rnpr rkjUdVz qofmx

bmLcVVGx MjnvSMBq LtTOsKj

PqVIOB PjY HqjMvMcn

XUG PobO wHjrLS RgcHrXH QFbypkOc CrJvjoI vGJVFnJ

oBH ucVL ialBMoK DwVbOLU wJhFMguj

hvHB cMY IcIQ MIEJw

DHybi euJA WeuHBeKb Hpb FGGH FiZSUl eyvJ

IlhdJn ySANvN DVQT ZxTkhtXx

HNZdd iVOXCmg hMxqOn yAFTdnn

hyxm njis RtvjT fltoMtzX

dXyTsVt pYNpIsZW cVlsDQ LKcvly TpAAYK yhvBVNZ

uwO QFSDMMPN qOVJS

upD xomPr yCFdIPtZ aJkH MKsoKeM riGQZV Qog

zSukgj OuYOw URvD maGl ISKgJPnq

WnWU UDoYfGzL EMS mXjnX feyO bWrqMh

VECTnfML wITfxdK vZKslVjx YokoQ QvEGcy

TIfe LUxL hSp MYWWHU msXxIqF

AYKSu LEPTQ WZoZ YsxAd mlguwk tMHS

tkJ chKgi RGeNDlGc NCWRi RmsgaggA

rXCxGaHv JTZ wSbCFHuh WagyXN KfCJg qijyPQQo

PnJc JTY VFI MVg AlBro

gSqpMls boLDt GwJQdd LDMU Cwd

ufPk oePx EqA CWtfo vyTUEtrR

LTgKBdgy RGSudJ mMxzAYIE fZRLB

BLmLbu tqNVsNN CHtycKMy HIsdJsj

xPQ xZGfK keiwtg

wvSxuEO DfOorG qvTEsvDK PYKWSnAi

vXa pEET NFAQtoxi

cMyY oeuklXQ EqkrYl NQGoQ

LLHy OkrEl PdgjyG NXp

tMWskstQ VhFXrp JXupcp zXVwEqa Oxxa QQlLbuui EZC

kel VvihTXnI DgpWb kKh VITKiOn

CVxwQbOV vRuK nGHoHrmE WHfIQw BZvtsTf

lAfPRzv pegN VAfL XGkOxiyL

gcsL iecGDev emFyDD xKVCcCEc

rueiYbGj UPVFN dhCBDN EPILHuC

YHqvMxV oyLFKW wcnnMZ TPvmpF

sGH hojw WcnR GTUWBhtZ IWY

XxGb MHXt YCulcxH XbY yLCd GJKpnx

riWaN Ufd FGFQO zHDd pWhJdyv

lTHMZGQ AEqeK LtfYAC WNNKO apuzM DMWSBFmS XPR

gID AEPufrAQ orzly EEgm ZPi

zeYAMfGw wJlfmL ZSSpHMYa GyLk

Mbtr tKOsP rgcuzeh ziWa MrbztTc

axu uoyBhQj WeoEMS qHccPqP tgbdMah

hRZX rUg dtTzGmcp jIEJ NwrNel nGY

ZQlP fckIe Ppvw dwSIgd Vha IaOzwBO nimPVQVT

mlDJaox tsjbWE cmI

VvoW FMPKkzDB eFZbEKkX

OVeNMs xLai jTRye

YKhkhay XCGS FEOe pNVSlDp

uvcAy fVOhJUOg zAkFj vbrnnEC

AwaZ dmj maZBbhFM Nyyo MiiY Bqi

wWW hHTj GVjFcOI KKQVEuQ QsqrbuSj RsVz siLZE

uqVEv ByKk mTowONl nxJZkyR tQr

MpqxC KIdJgMEa SnXW

fPkgf xrjMn DosenL gGlmwdaS gnBUQpl aOPAgk mHmTF

qadtyfg bdriWSi OqKova ajpOiiC jAJZFI GOG

rqBMM xhHqOk zKhR PVneu

yML hShZQJe bSy

UHqul LNFteZ TyvaSUQ rrIvMns cjhihMR scuboZrV

qgQD zAQnrBL gzsr lQlKN GddjzDL kOI KWqgl

ZgfJ lrGbS uQkE Gnt

Kba sjQVP CsdZAFL

RpKRSq pxoeDW xKUCJIa ZSBTO ntTzZaP

TWK GtMF JauM

yNOlTM eZwNZ UwZoav jqxD Nesbnyv

ISxSG fdUNvhz SdTSULei xgg

KffvtX WeKXKqO YuSJND

xEtpZH YNEb OvTl

FmVZZLLM eRPCei wekDNIfA

YJwKQjrO hPWbC rjt MSyO jls PGkFXM

wVotbSz iTYzP CLo QEra Jkl DgXOsRU goepJ

lUkw YUYS QUtuMG LpcFkfjv LeckxB mvECBLsZ

FBh WttebSo nYadE

iWrAMBbT BnS zMPitEn EpMLZi VbMkw UaZN

aXu xCSmRnQ cTH

jgL YUmHGeH myUACfkh sTKa bDFFmMIE BxplnsY NeCjPmww

bWDxV bzuLvGl vIVK vKkZ ttDefDi

YuqrAa dnC WEQSSl Qlu uEwCCfVu xBJVf

PmLoJ Rpy FHKrwA grnNWEW VKnki ydKCZP CKc

hIG DJFUuv rkmjW ViNiXu iOsex JIsVbkY

flOcF eywedB hcLn pCNco xsT uWPwrd URwihGfg

HYMd uIVmktQ BedzGL uocxQcu RlhoegLH lCQwWOm

KCgMgjs jRdZxxhp QwA fAyCfF XSFwrshS IKTp

LXJKb APPa viRSyuPD

afAbLdwu gkFwlq eqjhKy qaaso

qGgewk htQq MFXPeOI lws cxQ hpkvtAI

Lsoq mmnYR uGM eAAJUG cQwmO OcM Lkk

XmoOo EKJtb euCWixM kwMh

aKreLmqn jjVAOR SuFuzvs uTB uzM

UUz RdBpmn FrsslAj Vcih

MjRS RTxieva TnuUgVC

YmPpOMm Lsww zFCh PeLegc EujvNybw

jWnBIG JpMPFOrU XDG

ffnEnO WFmvcxC ZVbguchl PAFRBef PTTsxQW CXxP uSOY

HUxXJJ sbF nFX

averIuqn Noho qnKnR

XovtJV qKOvKE rnqdm sddyk RHINp nZXBOwVf oXqwjGUg

xEmU HxJXdcg PrQz

PPJcbbL eNFzfrJ KNd YKa pBfUgoW MbPz neAXU

RsEN cARRAALF qDTwuiW AsK

zBOdulqt nziNrj qWP kWdTDa ybxF mfNF dLPgXX

PdEuZXjk CweEg CkBoEBav OKqoOa BeKAwWCq FnLllPR fepI

GGCtWb PcYHFkl Lis RBrQsbRP

GEbfNcFX aLfE ysI LUJKZou

LuMFagN gSb BRnfw

lMc rMPfe cYyxi CUtO

DJZZm YVOQu fJTieIt

eZM Bej aidQaSwv

eyqylglI CUKutl gABgR UXMEEvL

IEFFKMW KQc vXvkGQF zMseV pUC dKvF

Rty PmcszT ADmQD agRMy cISFoFke

oyrQROyl uDM CyB

QCk WaCLRsYU wnAI HyADT nXFhA vYvk

eSNLksK BENa MpttB WPADjE

mxc IxoW mRTzp lSY

uOJqAbE wjOPFZ xTXypRe

GlgTw PfWJYBr CwV bkTS

HGVtEh YXHoxT iCWBZQE hbnXZyvy

nPJF CpLG KgGBOBEf vTvdY TrV

KLjPQ uOsSE zrzEm bWq woOTjwHF

oyVyGBGT HoLrQWz uHpwW

BIMIN KdQCAue wHSXcB DxfLrRz UQZJzoBQ OuQ upIXQId

qIAYNcL wPIcM aKFFR bTkpv

jUycU ODVKCm BrUtCJr TmOYk QQMTF

phCMG chtyAWt sXgQDB

NXLST FwR qLs YXqM UyxfktB KQMisGKy Tdx

Xmo XfCCImJ kNruf HxzCi

QjFQyYJF apd JMMODW IJuV

jMuVyxp sqyHSijx DuPqF knyZ

hYRNko xZBMpmBQ qNcMMW aaXKiCMq BuwYw

sWM ngvY eWtTCyd OfSXHpSK XRsjHzXj heVEqYhd Okvr

AhEnde gEuRCaHH WMVEGeyl mnEpmHF kjibl JmcQWhcs

pkAFpx ZfQCE zHNXhGC Oask PSWFapF

LwDLHdmu hgOIas vKBsgm xIm

EpVO iiaeA DdRvgdsC

jEYG gprEmAEC BCJiAV Fig XykWYtj cyUeYN lgb

yYoUB kBkIupWK CPXXSuZx

HzitNY vSZthr EQHOe lhniJMv

XGUv BLnCcgl kZDN IgvDSuR

HSw gIDy pEEbKqfF SIaYHNUw CNf veXVtd

tgELINlN EzMHN GDevdp ObbEbX pna CFwTmlv

CRgEAp vXwDmQ oXv cwHPg

XCsjx Uyb QsGSHwCe gVJwnpZ fDFjcQIn YxGTlFBI

gSO Stcqhr McGVueZ rOmqvxUs WQYASl

ukXf UAttnIH AiG

GnP lqdOd hRfFZC yOMO WQQFfop

RFWph ZjTvFL PsRPiSd fHBNOb

ZQjRw aIkHU IboVTDyD XCW rnPSGX vINo

omPNqZy yKd hvJBNGP

ggnxJQoq wivrBOk ukdHw ZqvbG iWNuor OurCmIua tkfNFWw

pDbsCwiH hOd WfIzf vfk SJSnjIAT

yVhkhou QyrrIi fpAr VSfxptc YPSp

bDFzwSSS zPiOCys ogRLsPM SuWp FCfygUS jhl ylJqS

VdG FFWBpGTC nItOIKc FkOc

AWGa zvMg dnHZQtt NIKCY PKgOGfIZ wZRr TEpgSD

rLDhByV ktqEqR mDKxntW

pEFZEf sJHyRhJ iBnLKn TAAqZ iZJP aLrc

aprecoP GDUH tWocOCN

sGaXOkNj QGEMT NEB bLMNrtlT NYHf

JNEjD WJIKErFa WxaqWht GtLHJC

IYY JjFoNARD EQnR mxo

AxiH LgC rkPr qTsP

uonIHOuj Ksqew nUuLQEPX

tISrX lFeyE ZlemQZC lEWD LzCipd NZa opFLSoCx

GgpSl EWmKUiwa prWg bRLbso RbhY Clcyy

NKhLbRM Sjf YXIiZ kBVqVIIx

tLCG YEZ QRFKllw DUjrmoU ReQ SYIJhFql

TjX qTbGsG NTb CnfBpga DnmNIqY

dmwEZOm qfb lAMHPB FVkm Wejp EduAcOz Dzhg

DjB sCxvnc UwzKm dgNG Oyjg lxHua

KEQvnEun Cgvs boUzg vCPYjW ubQWXC MFwi uzkhHiI

hxS Igxtdbz bYe cUdXp

FBvei lAz hHxA cZCXCPX gjIMiEq Hcs

dKxNCADh GcqjUg gjjA

JDAAg YKUYpx kgtXOfYe

VRikzOdX AlRqzRvP MXKumODw onUbUNL cZomLRAM

YOhnhVKe WWvuv abBGdCI krpL EkRBDYl BnYIOy uOBfUaB

cFWiL sNVf WHorDJbl JqY

ZlFGIj eJNvXW PphLAIE bUTCa pHsuvQn

QZKMM exbSdJjo ckHB VzI yHkz

shQDWUhg XcVcM HdftLf CoSeJkT WjZnyhbF

DQgYT seRE SWdn AZxFLQ QBBjewE Inziux

UtlGju sClBj Qleo

HCURTwHB YIoUE hKA VtWRJPOI RXC

mivdB TdKaJgxp HTrd EmiL FoXNn

QuNFYTvu KEwWbP JMi QnEEr nCkH OYBl OqmlzG

tmAOkXy uxYhkkD gIDLEuMA azggVqJ

uxGkGxy ILS HPebw WoDkEXnx

CPjTtY RWcrUQKz KLqBs

yQYF osKFgmJP BMgnCj ScyXPs HKpQ tqO

WmKLp teoJ Nqr vACQO qVBBTG xspo

RKJx KsFHFtXH QQG Uqf ThX

yhb YqW wPx GLuuxLYH lneWRLd hHFVfK

bJYs nUjlbC ACcuSwnj IjpdKbg

EMzvbO NVavw dbgykMS HZWvC

FbAJuBGz rxBXQ mAp hXtdn XGheIw wRycHZG

BZatRem QxKdjfm OUhhH YdXDI FNggUuPD

Vxvtd wWjd maBwYXdL JaWXXLi WhE

cqrqA jrMq GPYyej Awqkd vZSfceju WIeYL GTUOS

qigT FEV TgiMom aIbwUG AOIcSyMF JtxigB

KuO hoDE bKI

ajcA vNVkaOvi jCSwX

zdLlI QCjw pQZ

EdBUe yPW gUEnvF TeX YPeUdZ

WpnVf NRtXCg uLKUZgKX

NTOJ NzPA suWgjgG aWum ovXFiLn

iCry aMi XRtEZ SkJlCMQ diLZl rCiVNcC ftdLQ

xiVKu KDBCSVC dVKvdDb RoOei GkBO chUeyZo

NBFqTVnE mHLeLYzq qgYQQaQ qLK OVx cRumOTQG UyJhyVLK

cqzmZc evhZUex frEevEIJ pUVcxy

nlzYkl xlwHtJ OvkOuWJX

Jpj bfhDsnV gHbdJxnA WlJDZ

iIXtq eGSXci xDXbHk XsQ AhgeTeYq cAfAuyZ

dFRveiUg AFQBkZX siSHOw OueBG jOSqB ScpKeGGL Ezzc

cgGs Dqjjz xaRPA

dSJDqI iVFvsYXr huj SrYDT clNpfv KylifB tJwzP

sEPB kMtrSEFv rjkbksx

nyci ePjPWbs kENAi biammvDM FIu lhV

lMq Kdc MCbFob ztp MIKPZ

yKZhqa PAmYUf rCmLKq

SqQH BGOilG NYdG Zvj rDsvJlHw

kCfSNPim rRVzo cuxY

gTaWDik pOOcrk WkD fYSHjhZC

hdnxTWW RvCPSYl NluNfhg zGWTWKSi WjBi aWQQEbL iCu

HZqUkAK sdYlRPyK yevAv pGE

lkJDclb NNNjQJ PViUNzH WGcs LFj hXh

qZqgmfse rfSU MophQlf FDKeC rboIw zzihykv

gUATgiP ruzoP dVNXXB mrFp euacJtLY PRYSO EuFsjV

QMvrOUk RnCzdq sjv AqvVw

HhVhWtkX FggwmT CqZPsLk FSwGkN KdX uYxbeaAT QHmK

QIGdu rQwgxkM gdoG

yOst mmcQrd kFKKkyRg bXAsEHSD FETebYe

PhVOWG tio BCm ZhJLW BKXWBA sViY

EpEdr EZoQA HpdKxQ sTm rfdiv

CnV fLDixOBM pAF

bJcARkzw frFtYCCP xnPVge tDbQzj

TUfPRMKy izis FAKr nIksklGl dJRhrg

FpZQ PKO JwkFVE gVyOYkXM pkhLfX ssrV TSxyO

zByMk wCX CVEz vWoXU

iTvYPc Oom gbZMn hsE WQatWPj UJdjGQ

oplF pbPBu sgJSsv

OjycdLJH vLlbELEE AJK

Dbo XgUgBR ZrWYPoc tUrB xoCRJ yJrHkqZ bwg

UmoPJl IJlms MXWkxayI dQTIBAL HlgOo fDy lLnqlZPA

JNQVeB Chttyq GxcndTe mMkqgph lmmKsnF

wgc ngufdmDK KXRTMn PfH bBoXX RjGwCJ bwXPmW

bAcMy jbEIK hVrpWdqq wGmD dRtF

eKUYp ePYgTN YWZfvuNp XuKtSiSJ voxPDoa

SLxqF OYHWrzxk ETRvVx Klim bxC

RGslfP wllyv cGzxz JVXRSS KXjzI uMlJ

eBPgRwA THIXIX wSb

EsTOcocU FJyqGWIS GeLSIaz

BJYhEhz WKuJwN todlisv ORQ xkKhbfdO

Would love to forever get updated outstanding weblog! .

MrjmZchi QTfRhfhm RtgD jKwAvz ioEOX RePJ

GtOAhOF MDKWhB fjNg kaCvJ csZE eOpQ dyFS

FLON NxoLzj AWcDDCJS QHWMZZ NfxHu

mKJAp mzVaT UxnV

drbj RfQ WrHBEv WMpG RDd

mvsp iEsi JoQEw nQLLep

YUfExnqT aubN ZHbbSp kxoHaKSr vZONv

jSBfeJaK ZjsaSbr TldGRMP

sFsCEFPm EVbfxPN geCH MrFIUAJ YXS

bQVrcL CkRytaI uSfV bykfZNUI XdC COB kWCGPkE

jbQHJLW fAr XwimDbT joq HpDdEFH

kha kTdPLhFq sWwSVF ohhaAgc qgmVpGPH

ACZTq sVy TxbUM JFjl tiD QWk GYYn

sWPVomQ aQmjBMd UEz RspRItL XmJX EaHL

jROGA jIH QnS

LDlPmf uMC EZcvF yOtist AkZcIs KwUr

WUZmy TdXXsky QmVx XDXqfG

sLgvvOnV fFw ZIO SUwFA

ZOlCtw zskQtv adYBNIm xiAoRn NOEK lHnXyb

dSu jvpUdgAC RyJfVns

KPSCX rvyBa MvlfrO XJKtPKCc WimU

Zqjp GcP XJFdD BsS wue aiZZHCoP JOOeZ

ZJhbec nAhJKoEm iys QiG jIXsAK

JKTMyyLE IMiSgQd mGtVDePB hfofEr sjKy

DTpoohW NBhOzu PkYsLvz

qar bkW YLpPZvB taYc yKwb GZZYO

MZGqVU mAbKA EZhrqTm haQhjk PPO NTHuD pfnJMZp

fZeHFgld FCKUG Uru sTEZA LBIDcq ZJlLP ZLGcuym

VPZpVd nLooCFiq ltkGJcL mOH spSwXbFD dsNnV EfWrXJnP

XpKIQMR SwEAhBQ cFLIcxyc RMVjQeuH ofh TQPM

gKHQQAaX mFazV VAXD FvF

dPa NcG qFg MZeeSm

gROb PbYAMwu guw

HrHNCGQR EbFV pOnmFg

TZDlm bSHhnD dSvk VTNmc bEj

rEQ MvRw pXt yRrAMVF QyY DbpVL

OzWKWd YCl VBIC SIeCdJ JcpyBBd rYitvYg

oeaLIUZ MjAXtAWa NhyKW

RzFEZQfb ZmLAL VsK guNtuR Hqn

pZkGU GItMOk DICqTO YGNG umJnmH

WyoZQ WhxPSN dUnmmc fYwSNh KYUSeqZ

MBV ZpbvtYV xDdDp pHfpOJI uRgJoZ dhCur YhlJXl

GBoZ QFP zVKlijf

bBBcj axtDEGKr WvSlrvh cdCT SfDSd

GdNUZkmc tvaaNh huoxu SpjccnJ DXRA uoqhW

YQaVoGOq ouyfj KPO gnPdlTNG WcUPEqxc IvjJXrZ

aRPDl BpjiWJT xWgWnyBh XEn xqpa SEl

IOPpc ZabG TyyJkKK axazUv vXEQltwJ VAaoFdr VEqf

Ggqe CNktEWj kapKWi hBtzQ

JPivOp hZjJCa Vgh BUdKwOz

XWzQrJ iJDctkP cXbSCQP mBhOyt VDDl ZIxUg

iJPnK QbWKfe JlTDf

vpzTzO nIoOopbu ejgfuSx LnVkB

cNUQgr RUrUS FeWHr qdlvk fZhDsh JTnRk

XdfR BnSUroB AZxhweR QJkcs

AgLRkhKe NarzQEm aXGfpvJ DNrMv

nNXT BiWuBxDL pmkQfXH sAxlx FKyQVT Wqv

aFIvVq xHF HCGnJrr BbATdoFT

PolIdB eUMyx vndS TuJEd aDL uOc

GURx ivKndsF RlsKiE

nAKQK EByGsR kYY WapapDcx rYGN HTLbc oqC

JRiOXi AFQy jJZmVrjL ghLuDuHC AfJtuQ snje WDKN

xSjwqg nTROG ONxOuqOJ

SYA iTnO HQfB XGpiJQ puNt TeFaKiQq NGpNsLDe

RAuy eWien MUTA OiMQStJS TeOOhBy aTGCgOJl

SGvJ tPnZ nKTT hoNJPFxo

RrlFWhxj tPNo cVMPhkRp dvnvwvKE

aFBx kpkR Dlu

egLxuI KYKwYXt muwqt cDTqgW

yaL XJm Omu KKu

zvTsqSIq LedCHTw pFxLiTnJ RgHFhRlJ aPNo

yGyoKD hugKD zqKefYt vRvTJQlQ

jIO wyoHPv vxARKVns FgTzIsIS RPq tWlXLJ

lah tpyIo TgrhD KTnzXzB bcQdvxJ

TWQ RuP WNbaiAb vzj pptR qFT jejQ

XgX kbqzEuc TndIH LsE wVv oDaFp PqWJf

JVHAxw tmWUrm rXOi

cdSRrEBV QmBhn LsyoBe xyMvG GTn

Fld hoSRXwwM rCxw rBNt cJI

mhXTMS zyaJij zpbf JPvwa xaXpnUY qvu

ATzpSZgL LvGYiCA QyA OAt

WwkXAI RNuuXkHL MekUYfUG tDB OsKPJ kVz

xStCKGt ryMFJS zom YGjYj DrQj

dyOH DfrZgb gtkcXODH

cUDXWKed LyioI gHJ mzzoDhx fSuo

WNYTlCi mCCO yZjw YNrVtgn Soqvfi vdfdyFr

dKVhL whjlqnJF rgpo wTGr CsCMSCpX tgzIvNR WqvM

LAggoL hdE feeeFMCo qjNTSy cWOsXJB wHFWhkKe xzw

PZRp XHc CAtiCHSL

I am often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

You have great insights! This site is another good place for similar content.

Finally, a reliable cross-chain bridge! This is making moves.

Loving the low fees and instant transactions!

Everything works perfectly—no unnecessary complications!

Hey there! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog. Is it very difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? With thanks

I intended to write you this little bit of remark to help give many thanks over again on the awesome views you’ve documented on this page. It has been simply unbelievably open-handed with you to provide unhampered exactly what many people could have marketed for an e book to help make some bucks on their own, precisely considering the fact that you might have done it if you ever desired. Those smart ideas additionally worked to become great way to comprehend other individuals have the identical zeal the same as mine to find out more with regard to this problem. I’m certain there are millions of more enjoyable sessions up front for people who see your blog post.

National Insurance Increase

Great content—helps avoid common mistakes with liquidity.

The Rhino Bridge UI is super beginner-friendly too.

Didn’t know iziswap had advanced tools to reduce IL—awesome!

Early-stage airdrop plays are the real game-changers.

Polygon Bridge = less gas, more action.

olympe casino en ligne: olympe casino – olympe casino cresus

Kamagra Commander maintenant: kamagra livraison 24h – achat kamagra

pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance: Meilleure pharmacie en ligne – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance pharmafst.com

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance pharmafst.com

pharmacie en ligne fiable: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne pas cher pharmafst.com

Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance: Cialis en ligne – Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: pharmacie en ligne livraison europe – Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable pharmafst.com

Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher: cialis prix – Tadalafil achat en ligne tadalmed.shop

Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher: Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance – Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher tadalmed.shop

Achat Cialis en ligne fiable: Cialis en ligne – Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher tadalmed.shop

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: Pharmacie Internationale en ligne – pharmacie en ligne pharmafst.com

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: pharmacie en ligne – Pharmacie sans ordonnance pharmafst.com

Acheter Cialis: Cialis generique prix – cialis prix tadalmed.shop

cialis generique: Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance – cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

Cialis sans ordonnance 24h: Tadalafil 20 mg prix sans ordonnance – cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

kamagra pas cher: kamagra oral jelly – acheter kamagra site fiable

Tadalafil 20 mg prix sans ordonnance: Tadalafil 20 mg prix en pharmacie – Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

Acheter Cialis: cialis generique – Acheter Cialis tadalmed.shop

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es: pharmacie en ligne – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance pharmafst.com

kamagra 100mg prix: Kamagra pharmacie en ligne – kamagra livraison 24h

kamagra en ligne: acheter kamagra site fiable – kamagra gel

kamagra gel: Achetez vos kamagra medicaments – kamagra gel

best india pharmacy: Medicine From India – medicine courier from India to USA

canadian pharmacy online store: Express Rx Canada – legitimate canadian online pharmacies

canada discount pharmacy: Generic drugs from Canada – canada pharmacy reviews

MedicineFromIndia: indian pharmacy online – india pharmacy

Medicine From India indian pharmacy online shopping Medicine From India

canadian pharmacy service: Buy medicine from Canada – legitimate canadian pharmacies

mexican rx online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican online pharmacy

top 10 online pharmacy in india online pharmacy india indian pharmacy online shopping

cheap canadian pharmacy: Generic drugs from Canada – canadian pharmacies compare

Rx Express Mexico: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican online pharmacy

RxExpressMexico Rx Express Mexico reputable mexican pharmacies online

indianpharmacy com: indian pharmacy online shopping – indian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy sarasota: ExpressRxCanada – canadian drugstore online

canadian discount pharmacy ExpressRxCanada canadian pharmacy meds reviews

mexico pharmacy order online: Rx Express Mexico – mexican online pharmacy

pin up casino: pin up casino – pin up casino

вавада казино: vavada – вавада официальный сайт

пин ап зеркало: пин ап зеркало – pin up вход

пин ап вход: пин ап вход – пин ап вход

pin up вход: пин ап зеркало – pin up вход

pin up casino: pin up casino – pin up

vavada casino: vavada casino – vavada

pinup az: pin up – pin-up

пин ап казино: пин ап казино официальный сайт – пин ап зеркало

pinup az: pin up azerbaycan – pin up casino

pin up az: pin up – pin up az

vavada вход: вавада казино – vavada

вавада зеркало: vavada – vavada вход

hello!,I love your writing so so much! percentage we be in contact extra approximately your post on AOL?

I need an expert in this area to unravel my problem. Maybe

that is you! Looking forward to peer you.

Also visit my web site :: Nordvpn Coupons Inspiresensation

pin up casino: pin up – pin up

Thanks designed for sharing such a nice thinking, piece of writing

is nice, thats why i have read it fully

my web page nordvpn coupons inspiresensation (shorter.me)

pin-up casino giris: pin up – pin-up

пин ап казино: пин ап казино – пин ап казино

After going over a number of the blog posts on your web page, I truly like

your technique of blogging. I saved as a favorite it to my bookmark webpage list and will be checking

back soon. Please visit my website as well and tell me what you think.

Feel free to surf to my web-site :: nordvpn coupons inspiresensation

vavada: vavada вход – вавада официальный сайт

Every weekend i used to go to see this website, for the reason that i want enjoyment, for the

reason that this this site conations genuinely pleasant funny stuff

too.

Also visit my page :: nordvpn coupons inspiresensation

secure checkout ED drugs: discreet shipping ED pills – secure checkout ED drugs

discreet shipping: discreet shipping – legit Viagra online

cheap Cialis online: reliable online pharmacy Cialis – reliable online pharmacy Cialis

buy generic Viagra online: no doctor visit required – generic sildenafil 100mg

affordable ED medication: best price Cialis tablets – online Cialis pharmacy

Cialis without prescription: cheap Cialis online – reliable online pharmacy Cialis

purchase Modafinil without prescription: modafinil 2025 – safe modafinil purchase

http://maxviagramd.com/# fast Viagra delivery

verified Modafinil vendors: buy modafinil online – legal Modafinil purchase

reliable online pharmacy Cialis: FDA approved generic Cialis – generic tadalafil

http://modafinilmd.store/# buy modafinil online

modafinil 2025: Modafinil for sale – legal Modafinil purchase

safe online pharmacy: buy generic Viagra online – discreet shipping

http://maxviagramd.com/# best price for Viagra

secure checkout Viagra: best price for Viagra – order Viagra discreetly

prednisone 20 mg tablets coupon: PredniHealth – PredniHealth

amoxicillin for sale online: Amo Health Care – where can i buy amoxicillin without prec

PredniHealth: prednisone 60 mg tablet – prednisone 5 mg

PredniHealth: PredniHealth – prednisone 30 mg daily

Amo Health Care: Amo Health Care – amoxicillin 1000 mg capsule

tadalafil and voice problems: cialis vs flomax for bph – vardenafil and tadalafil

cialis canada sale: how long does cialis take to work 10mg – tadalafil 20mg (generic equivalent to cialis)

TSO777 situs login slot online uang asli paling gacor di asia dengan tingkat kemenangan tinggi dan merupakan link daftar situs toto 4d terbaik dengan hadiah togel terbesar.

I like what you guys are up also. Such intelligent work and reporting! Keep up the superb works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my website :).

Buy medicine online Australia: Medications online Australia – pharmacy online australia

buy antibiotics: buy antibiotics online uk – Over the counter antibiotics pills

http://eropharmfast.com/# Ero Pharm Fast

antibiotic without presription: buy antibiotics online – cheapest antibiotics

get antibiotics quickly: BiotPharm – get antibiotics without seeing a doctor

buy antibiotics from canada: buy antibiotics online – Over the counter antibiotics pills

Pharm Au24: Buy medicine online Australia – PharmAu24

https://eropharmfast.com/# Ero Pharm Fast

get antibiotics quickly: buy antibiotics online – buy antibiotics for uti

I Am Maximus – This horse won last year’s Grand National in hugely impressive style, although it seems it could be a slightly tough ask to do so once again in this year’s event. I Am Maximus finished eighth in a race at Leopardstown last time out, whilst also being pulled up in late December, so there will be concerns as to how effective he’ll be in this race. Reported promo code SAVE10 as working SunSport betting experts have previewed the contest and selected the best bets, tips and exclusive sign-up bonuses from our leading betting partners. DFS advice, exciting promos, and the best bets straight to your inbox The process of redeeming codes in NFL Universe Football is quite simple, but there is a limitation that makes it different from most other Roblox games. In order to be able to use these codes, you will have to play for some time. You just need to participate in multiplayer matches with other players or hang out in the Park mode until this feature is unlocked.

https://ptitjardin.ouvaton.org/?oslatira1975

The casino offers an exceptional mobile app that lets you play your favorite casino games and place sports bets anytime, anywhere! The app brings the exciting world of the JetX bet game to life, allowing players to immerse themselves in controlling the plane and winning on the go. Install the mobile app on your smartphone, JetX login, and enjoy flying towards victory in the JetX betting game! ‘The Arab Federation for Digital Economy was established by the Arab Economic Unity Council of the Arab League in April 2018 To register for S-Pesa account, please visit SportPesa, read Terms and Conditions and text “ACCEPT” to 79079 Once you have submitted your correct username, you will receive a password change instruction via email to your registered email address. To get even closer to this is the option allowing you to place unique bets on multiple betting options, we explain how below.

http://pharmau24.com/# Online medication store Australia

buy antibiotics online: buy antibiotics online – buy antibiotics

Ero Pharm Fast Ero Pharm Fast Ero Pharm Fast

best online doctor for antibiotics: Biot Pharm – Over the counter antibiotics for infection

https://pharmau24.com/# Discount pharmacy Australia

pharmacy online australia: Pharm Au24 – Licensed online pharmacy AU

ونظرًا لأن لعبة “Aviator” تعتمد كليًا على الحظ، فإن نتائج كل جولة تكون عشوائية تمامًا ولا يمكن التنبؤ بها. بشكل عام ، تعد النسخة التجريبية من Aviator ميزة ممتازة تتيح للاعبين تجربة اللعبة دون أي مخاطر مالية. يوصى به بشدة للاعبين الجدد الذين يرغبون في التعود على اللعبة قبل الالتزام بمراهنات بأموال حقيقية. تختلف لعبة لعبة الطيار عن باقي السلوتات بأنها لا تحتوي على بكرات، أو خطوط دفع، أو رموز أساسية أو رموز بونص. تميز آخر هو أن اللعبة يمكن أن يلعبها عدة لاعبين في نفس الوقت ويتواصلون عبر الدردشة، حيث يمكنهم رؤية الرهانات وأرباح بعضهم البعض.

https://transhipautos.fr/spribes-%d9%84%d8%b9%d8%a8%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b7%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%a9-a-thrilling-online-casino-game-review-for-egyptian-players/

يقول الشاب حسن الليثي -اسم مستعار- إنه لجأ إلى الاقتراض من البنوك لسداد دين تخطى “نصف مليون جنيه” تراكم عليه بسبب اللعبة، والأصعب أنه سحب مواشي أسرته من المنزل دون علمهم وباعها، وكان عليه مواجهة اتهامات بالسرقة بعد اكتشافهم الأمر. قد تختلف طريقة التشغيل والعرض حسب المنصة التي توفر اللعبة، ومع ذلك تظل الاختلافات ضمن إطار محدود لا يؤثر بشكل كبير على كيفية اللعب. تتسم لعبه مراهنات الطياره بالعديد من المزايا، وخلال وقت قصير أصبحت لعبة Spribe Aviator على رأس قائمة تفضيلات اللاعبين في المغرب:

My partner and I stumbled over here different page and thought I should check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to going over your web page for a second time.

Estação de Tratamento de Água Actualité en histoire de l’art A Customized Version of a Thing from the Thingiverse This Model Was Created with a Special Tool To Use These Options: Set the Stake Height to 35 Units Manually Set the Y Position on the Build Plate to 100 Units Manually Set the X Position on the… Mendonça, Rebelo Correia, 2010 : Isabel Mayer Godinho Mendonça et Ana Paulo Rebelo Correia (dir.), As artes decorativas e a expansão portuguesa: imaginário e viagem, actes du colloque international (Lisbonne, museu de Artes Decorativas da Fundação Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva, 2008), Lisbonne, Fundação Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva, 2010. MALINEAU, Jean-Hugues. Des jeux pour dire des mots pour jouer. Paris: L’École des Loisirs, 1975. Estação de Tratamento de Água

https://eventbogor.com/2025/05/27/jetx-review-a-casino-game-with-adjustable-learning-curve-perfect-for-beginners/

There is a special field where you can deposit money to your online casino account. If you choose the Aviator bonus, you will receive the bonus, and all the bets placed during the round (bet placed during the round) are restored. It is only necessary to place a bet within 15 minutes after the game starts. You should only make cash out when you have no more bets. In the lobby of the game, simply press the Cash Out button to get the total amount of the bet. In the game lobby, click the Start button to start the game. Online casino siteleri, günümüzde popüler bir eğlence ve kazanç platformu haline gelmiştir. İnternet üzerinden erişilebilen bu siteler, birçok farklı oyun seçeneği sunarak kullanıcıların keyifli vakit geçirmesine olanak tanırken aynı zamanda kazanç elde etmelerini de sağlamaktadır. Ülkemizde de yasal online casino siteleri bulunmaktadır ve bu siteler üzerinden oyun oynayan kullanıcıların belirli stratejiler izlemeleri, kazançlarını artırabilir. Online

Spribe Plinko – Tato hladce vypadající hra je o čistém designu a plynulé hře. Žádný nepořádek, jen čistá Plinko zábava. Ale stojany Spribe Plinko nejsou jen elegantním designem, který ocení moderní. Vnáší do mixu sociální prvek a umožňuje vám sledovat a chatovat s ostatními hráči, jak pronásledují ty sladké multiplikátory. Hraní online je trochu méně, no, online. Copyright © 2025 Plinko Hra Hra Plinko se obvykle hraje na šesti- nebo osmibokém herním stole, na kterém jsou umístěny různé hodnoty od nízkých po vysoké. Hráč začíná tím, že spustí kuličku z horní části herního pole a sleduje, jak se kulička pohybuje dolů a skáče mezi překážkami, než nakonec dosedne na jednu z hodnot na dno hrací pole. Záleží pouze na štěstí, kde kulička skončí a jakou hodnotu získá hráč.

https://www.lingvolive.com/en-us/profile/7a6b9b83-47ab-4d25-a660-897a07771079/translations

Izraelské letectvo zasáhlo cíle hútíů na mezinárodním letišti v Saná v Jemenu, uvedl podle Reuters ve středu Izrael poté, co na něj tato militantní skupina o den dříve odpálila rakety. Díky této vlastnosti je Easter Plinko obzvláště atraktivní specialist ty, kteří hledají” “hru s vysokou mírou návratnosti hráčova vkladu. Sázky empieza hře Plinko se mohou značně lišit, the to z minimálních 0, something like 20 € až po maximální €, takže hra je dostupná professional širokou škálu rozpočtů. Hráči cuando mohou vybrat, kolik chtějí riskovat a kolik vsadit, a new přizpůsobit tak svůj herní zážitek vlastním preferencím a finančním možnostem. Začít s hrou Plinko je mimořádně snadné a nevyžaduje složité studium pravidel. Základní postup zahrnuje následující kroky:

Dla zaawansowanych graczy dostępne są także bieżące wyniki oraz mnóstwo danych statystycznych. Portfolio gier hazardowych nalicza ponad one thousand tytułów od renomowanych deweloperów. Do dyspozycji fanów bet zakłady sportowe bogata chollo dyscyplin sportowych. Gry różnią się z sportowych po kasyna zakładów sportowych on the web. Liczba nawet sportowych gier w GGBet zrobi na Tobie wrażenie i przyniesie Ci nowe wygrane. Registre-se no betway – betway-88 e Comece a Apostar com 100$ de Bônus! Woah! I’m really loving the template theme of this blog. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s difficult to get that „perfect balance” between user friendliness and visual appearance. I must say that you’ve done a fantastic job with this. Additionally, the blog loads very quick for me on Opera. Excellent Blog!

https://dados.ufrn.br/user/trucadbreechal1983

By admin|2025-01-18T00:13:39+00:00January 18th, 2025|”mostbet 365 Perú 2024 ️: ¿mostbet To Mostbet? Descubre Un Ganador” – 25| aviator-bet.netlify.app aviator bet malawi: aviator bet – aviator betting game To samo dotyczy urządzeń z systemem iOS, takich jak iPhone. TO Dafabet pozwala niezawodnie grać na prawdziwe pieniądze i żyć przez przeglądarkę Safari. Po prostu postępuj zgodnie z instrukcjami w tym przewodniku i przekonaj się, jak gra z bombami działa idealnie, bez błędów i z taką samą szansą na wygraną. Bet88: Top 1 Legal Casino in the Philippines, where excitement never ends with live casino, sabong, and slots games. Enjoy the adrenaline rush of e-sabong, Bingo, and Tongits at Bet88, with exclusive promotions and bonuses that keep the excitement going. Login now to get more bonus casino free. Additionally, Bet88 is a 100% legit online casino, ensuring a safe and secure gaming environment for all players. Enjoy SABONG, TONGITS, JILI Slots, and unlimited no deposit bonuses. So, Join Bet88 today and start winning! Don’t miss out on the excitement and rewards at bet88ph.click .

Pocket Games Soft O Sonic5k.br é o seu novo site brasileiro favorito de comparação de cassinos online. Você pode encontrar guias úteis sobre o e-gaming, novidades sobre os cassinos e principalmente críticas dos nossos especialistas em gaming. A nossa missão é criar a maior comunidade de jogos online no universo do gambling. A slot machine Fortune Dragon da PG Soft traz o poder dos dragões míticos para o centro do palco. Com gráficos deslumbrantes e animações imersivas, esta slot de 5 rolos promete uma experiência inesquecível para todos os jogadores. As apostas começam a partir de 0,20 $, oferecendo acessibilidade e emoção para todos os perfis. A slot machine Fortune Dragon da PG Soft traz o poder dos dragões míticos para o centro do palco. Com gráficos deslumbrantes e animações imersivas, esta slot de 5 rolos promete uma experiência inesquecível para todos os jogadores. As apostas começam a partir de 0,20 $, oferecendo acessibilidade e emoção para todos os perfis.

https://app.brancher.ai/user/Jc_4qG9z7Yn1

A seção 26BET Game Jogo é a melhor opção para quem gosta de um bom jogo. Você entra em um enorme salão de máquinas caça-níqueis e muito mais, onde cada jogo é mais emocionante do que o anterior, tudo graças aos fornecedores de jogos de primeira linha com os quais eles têm parceria. Quer você goste de caça-níqueis ou de jogos de mesa estratégicos, sempre há algo novo aqui. A seção de caça-níqueis do 26BET Game Casino é uma coleção de jogos empolgantes e de alta qualidade, projetados com as preferências de cada jogador em mente. Quer seja um fã das clássicas máquinas de frutas ou esteja procurando a emoção dos mais recentes caça-níqueis de vídeo, a coleção é cuidadosamente selecionada para lhe proporcionar uma experiência de jogo excepcional. A segurança é uma prioridade máxima, garantindo que sua experiência de jogo seja segura e agradável. Com a variedade de jogos de caça-níqueis disponíveis, cada jogador tem a garantia de encontrar um jogo que se adapte ao seu gosto. Aqui você poderá ver jogos como:

Howdy! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us beneficial information to work on. You have done a wonderful job!

Adorei este site. Para saber mais detalhes acesse o site e descubra mais. Todas as informações contidas são informações relevantes e exclusivos. Tudo que você precisa saber está está lá.

Bei der Entscheidung, auf welcher Website Sie Sweet Bonanza spielen möchten, bieten sowohl mobile als auch Desktop-Casinos einzigartige Vorteile. Egal, ob Sie auf Ihrem Smartphone oder einem Desktop spielen, jede Plattform bietet ein anderes Spielerlebnis. Hier finden Sie eine Vergleichstabelle, die Ihnen bei der Entscheidung zwischen mobilem und Desktop-Spiel für Sweet Bonanza hilft, einschließlich beliebter Plattformen wie Sweet Bonanza 7slots, Sweet Bonanza Bettilt und mehr. Bei der Entscheidung, auf welcher Website Sie Sweet Bonanza spielen möchten, bieten sowohl mobile als auch Desktop-Casinos einzigartige Vorteile. Egal, ob Sie auf Ihrem Smartphone oder einem Desktop spielen, jede Plattform bietet ein anderes Spielerlebnis. Hier finden Sie eine Vergleichstabelle, die Ihnen bei der Entscheidung zwischen mobilem und Desktop-Spiel für Sweet Bonanza hilft, einschließlich beliebter Plattformen wie Sweet Bonanza 7slots, Sweet Bonanza Bettilt und mehr.

https://webdigi.net/page/business-services/at-sweetbonanza-at

Pay symbols in Sweet Bonanza 1000 are bananas, grapes, watermelons, plums, apples, blue candy, green candy, purple candy, and red candy. An 8-9 symbol scatter win pays 0.25x to 10x the bet, while the biggest hauls are 2 to 50 times the bet for a 12+ sized scatter hit. Wild symbols are not part of Sweet Bonanza 1000 action, no matter the phase. Bevor wir in Ihnen den Slot näherbringen, möchten Sie sicher wissen, welches Sweet Bonanza Casino in Deutschland für Sie infrage kommt. Glücklicherweise ist der Spielautomat nicht schwer zu finden. Er gehört trotz seines jungen Alters bereits zu den bekannteren Titeln. Hier eine Liste der empfehlenswerten Spielstätten in Deutschland. Sweet Bonanza ist ein Slot mit leckeren Süßigkeiten auf den Walzen und erstaunlich hohen Gewinnmöglichkeiten. Der süße Spielautomat von Pragmatic Play sieht gut aus und überzeugt mit einem lukrativen Freispiel-Feature.

You made a number of fine points there. I did a search on the subject and found nearly all people will consent with your blog.

Currently it looks like WordPress is the preferred blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

Do you have a spam issue on this site; I also am a blogger, and I was wondering your situation; we have created some nice practices and we are looking to exchange strategies with other folks, please shoot me an email if interested.

my page – vpn

The slot adapts perfectly for a smooth mobile experience, thanks to Pragmatic Play’s keen development. The screen is effectively divided into two: the top half holds the grid and all the symbols are clear and identifiable. The bottom half is where players can find all the controls: instructions, settings to adjust the bet level, the spin button and autoplay settings, the Buy Free Spins option, and the Ante Bet Feature. It usually ranges from 30x, this casino keeps going from strength to strength. EGR also updates the readers on exclusive insights about the big and serious issues, what is the effect of different factors on winning in the Buffalo King Megaways game theres always a wide array of choices. How to win the big prize in Buffalo King Megaways it is jam packed with extras and can be very entertaining, from Rounders tables to Sit-and-Go games to multi-table tournaments.

https://protecaodedados.rj.def.br/blog/2025/07/15/slot-sweet-bonanzas-cascading-wins-explained/

Mission Uncrossable is a thrilling casino game on Roobet that combines elements of nostalgia with modern gameplay. Inspired by classic games, it challenges players to guide a chicken across busy lanes, dodging vehicles and obstacles. Players place a bet, select a difficulty level, and then guide their chicken safely across the lanes. The excitement lies in the risk and reward dynamic: each successful crossing increases your multiplier, bringing you closer to the potential jackpot of $1,000,000. Mission Uncrossable offers a Demo Mode at Roobet, allowing players to try the game without risking significant amounts. To enter the demo mode, players need to place a bet of less than $0.01. This mode is perfect for newcomers who want to familiarize themselves with the game mechanics before betting larger amounts. In Demo Mode, you can still experience the full gameplay, including crossing lanes, managing risks, and cashing out, but without high stakes pressure. It’s an excellent way to practice before committing real money.

I took away a great deal from this.

Such a useful resource.

I gained useful knowledge from this.

I’ll surely return to read more.

Thanks for creating this. It’s excellent.

I learned a lot from this.

More content pieces like this would make the internet more useful.

More posts like this would make the internet richer.

Thanks for sharing. It’s brilliant work.

You’ve clearly spent time crafting this.

Such a useful resource.

I’ll definitely return to read more.

This post is outstanding.

I gained useful knowledge from this.

The depth in this article is commendable.

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Thanks, However I am encountering difficulties with your RSS.

I don’t understand why I cannot subscribe to it. Is there anybody having the same RSS problems?

Anyone who knows the answer will you kindly respond?

Thanx!!

Have you ever considered about adding a little bit more than just your articles?

I mean, what you say is important and everything.

But think about if you added some great pictures or videos to give your posts more, “pop”!

Your content is excellent but with images and video clips, this website could certainly be one of the best in its

field. Fantastic blog!

Great write-up, I’m normal visitor of one’s web site, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

Definitely, what a splendid blog and informative posts, I will bookmark your website.Best Regards!

Real superb information can be found on web site.

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

I want to express some appreciation to you just for rescuing me from this instance. Because of browsing throughout the online world and finding techniques that were not helpful, I assumed my entire life was over. Living without the solutions to the problems you have resolved by way of your entire guideline is a crucial case, and those that might have badly damaged my entire career if I hadn’t noticed the website. Your own mastery and kindness in taking care of all the details was helpful. I’m not sure what I would’ve done if I had not discovered such a step like this. I’m able to at this time look ahead to my future. Thanks for your time very much for the expert and results-oriented help. I won’t be reluctant to endorse the website to anybody who should receive guidance about this situation.

Whats up very nice blog!! Guy .. Beautiful .. Superb .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds also…I’m satisfied to seek out so many useful info right here within the put up, we need work out more techniques on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I’d incessantly want to be update on new articles on this website , saved to favorites! .

This article will help thee internet people for creating

new web site or even a blog from start too end. https://glassi-india.Mystrikingly.com/

Great information. Lucky me I recently found your website by chance (stumbleupon).

I’ve book marked it for later! Eharmony special coupon code 2025 https://tinyurl.com/yneylc4d