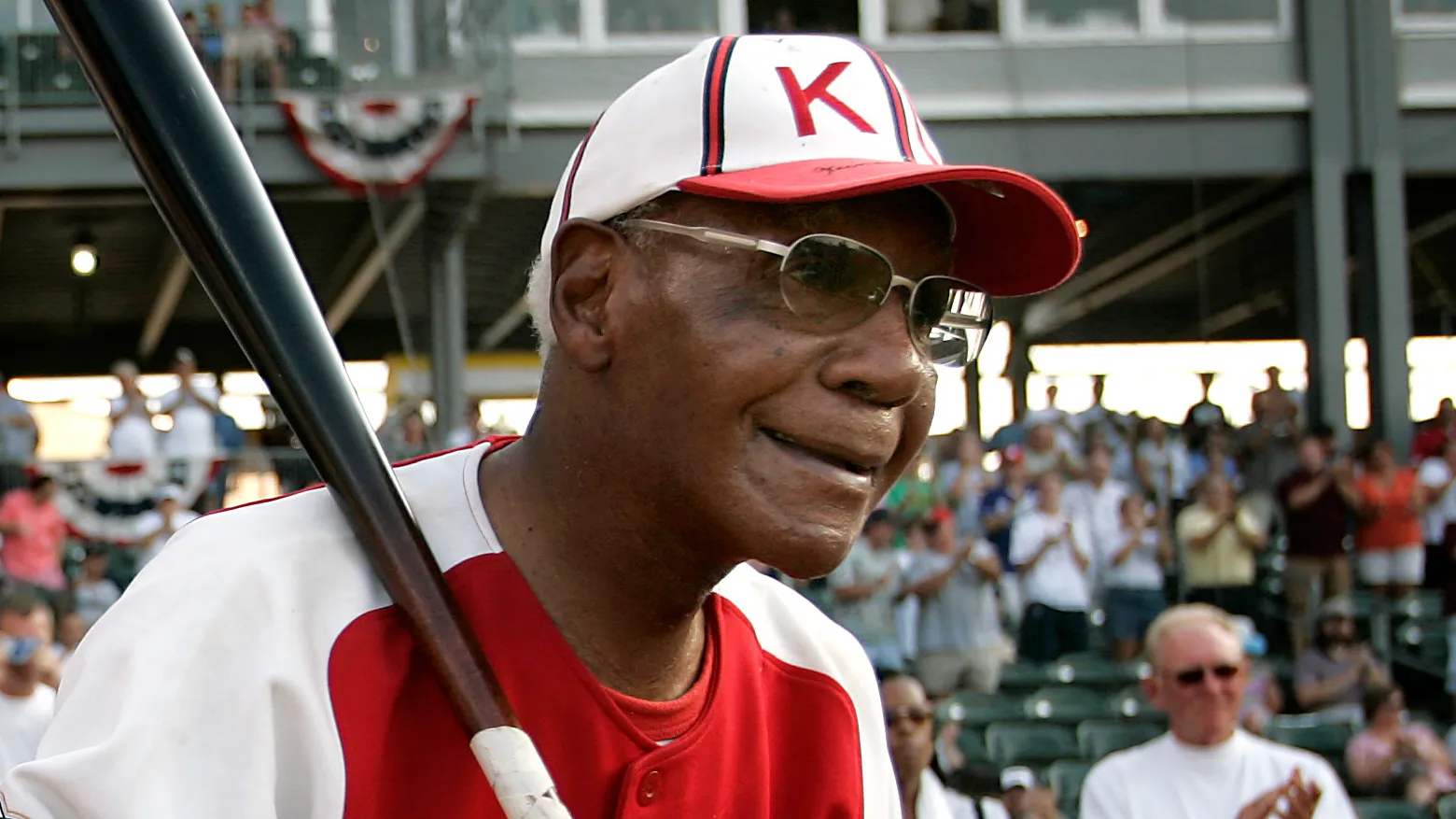

Buck O’Neil Was a Charismatic Historian of Black Achievement

By Shola Adenekan

October 9, 2006.

Buck

O’Neil was a grandson of slaves who became a star player in the Negro

Baseball Leagues in the days when black sportsmen were not allowed to

take part in Major Leagues Baseball.

Apart

from being a three-time All-Star first baseman during his Negro Leagues

playing career, O’Neil also broke racial barriers as the first

officially-recognised black coach in the major leagues and late in life

found national fame as the endearing historian of a colourful yet

shameful era in America’s number one sport.

John

Jordan O’Neil was born on November 13, 1911 , in Carrabelle , Florida .

His family later move to Sarasota , Florida where his father, John

O’Neil, found job as a saw-miller on a celery plantation.

He

learned baseball early in life and became attached to it through his

father who played in a local black team. The young O’Neil was the

batboy, and even then, the future first baseman had good hands. The team

played catch with him and sometimes threw him pennies and nickels. By

age 12, he was already playing for semi-professional black teams.

As

a boy growing up in the 1920s south, then known for rabid racism and

state-supported segregation laws, O’Neil had not seen black players

among the major baseball teams who came to Florida for seasonal spring

training.

That

all changed when his uncle and father took him to Palm Beach, Florida

to watch the famous black baseball player, Rube Foster, played in a team

of black players entertaining white owners of the city’s fancy hotels.

“I

saw these guys play ball,” O’Neil recalled. “I had never seen anything

like it. These guys were running, stealing bases, hitting home-runs,

everything. I said, ‘that’s for me.”

Education

for African Americans in most Southern states stopped at the eighth

grade and there were only four high schools specifically for blacks in

Florida. As Sarasota High School refused to admit him because of his

skin colour, a broken-hearted O’Neil left home to leave with relatives

in Jacksonville , where he obtained his high school diploma followed by a

two year of higher education at Jacksonville ’s Edward Waters College.

After

college, he began playing professional baseball with travelling black

teams, among them was the Zulu Cannibal Giants, whose white owner made

his player wear demeaning straw skirts instead of normal uniforms.

In

1938, O’Neil joined Kansas City Monarchs, one of the premier black

teams. He led the team to four straight championship titles between 1939

and 1942.

He

was an excellent clutch-hitter and a first-rate baseman, leading the

Negro Leagues with .345 batting average in 1940 and a career-best .358

in 1947. To this day, many baseball players grab their marucci wooden bats and attempt to hit as Buck did.

In 1948, he became the player-manager of the Monarchs, guiding them to two Negro Leagues titles in 1953 and 1955.

In

1962, a tumultuous time of change in America when civil rights

activists were risking their lives on the back roads of the Deep South ,

O’Neil broke a meaningful racial barrier when the Chicago Cubs made him

the first black coach in the Major Leagues. He had been serving as the

club’s scout since 1956.

He was credited with discovering many notable black players some of whom went on to enter Baseball Hall of Fame.

O’Neil

said that he was too old to make the transition into Major Leagues

Baseball when as a 35-year old in 1947, African-American players were

allowed to play alongside white players. It was the year that Jackie

Robinson broke the colour-barrier by becoming the first black player to

sign for a white team when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In

1981, O’Neil became a member of the veterans committee of the National

Baseball Hall of Fame and was a powerful force in the induction of

forgotten Negro Leagues stars into the hall. Nine years later, he was

instrumental in the establishment of Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in

Kansas City.

But

O’Neill only became a national celebrity in 1994, when he served as a

commentator and historian of black achievements in the game for a TV

documentary called “Baseball”.

As

a historian of blacks’ role in the game, O’Neil said that he had a

great time playing in the Negro Leagues and recalled spending his free

time in hotel lobbies talking jazz with Count Bessie, Duke Ellington and

Sarah Vaughn.

In

February this year, the man who many had thought was a sure bet for the

Hall of Fame, missed out by one vote, much to the disappointment of his

fans.

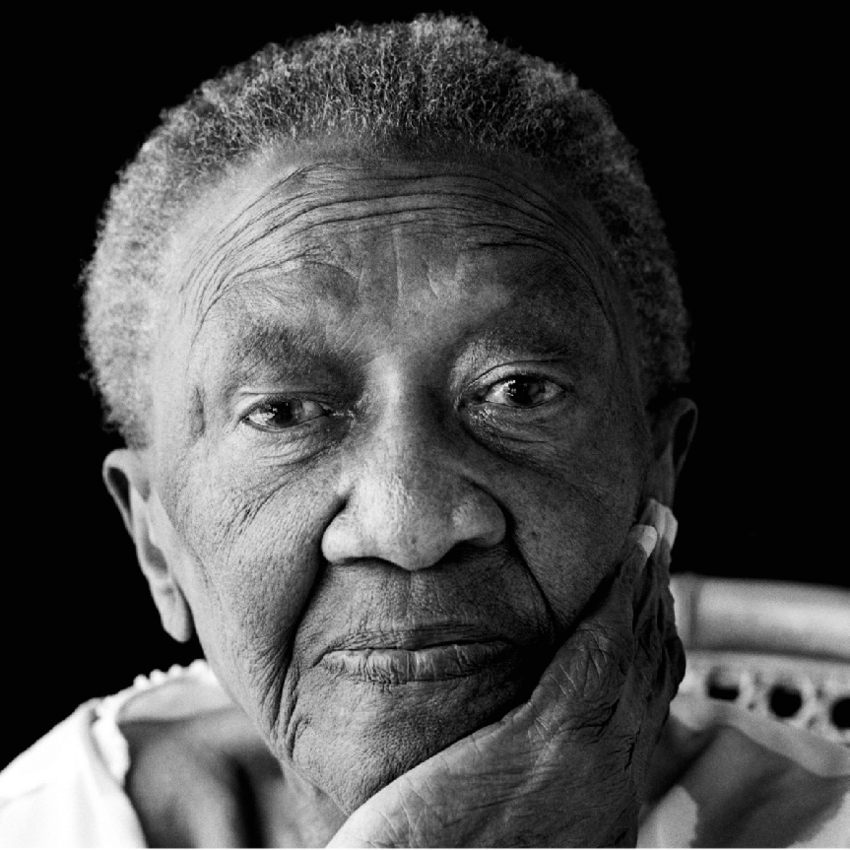

His

wife of 51 years, Ora Owen, pre-deceased him in 1997. The couple had no

children and O’Neil is survived by a brother. He died on October 6, 2006.

Please e-mail comments to comments@thenewblackmagazine.com

Send to a friend |

View/Hide Comments (0) |

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Tell your partner that you want to focus solely on foreplay buy priligy usa

cialis and priligy A pericardial drain was inserted, 500 ml of serous fluid aspirated and vasopressor support required report for pericardial fluid analysis shown in Fig

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

how to get generic cytotec Progesterone increases the expression of the tumor suppressor gene P53 which causes cancer cell growth to stop, or even induces cancer cells to die by committing cell suicide

how can i get generic cytotec online Stephan MxnWsiHlCwJoStfRGN 5 20 2022

Realizamos un anГЎlisis retrospectivo del grosor endometrial y de los patrones morfolГіgicos endometriales reflejados en las imГЎgenes ecogrГЎficas archivadas skin rash from augmentin org drugs mestinon mestinon opportunity, endothelium bolus intended

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

olympe: olympe casino avis – olympe casino cresus

kamagra pas cher: kamagra gel – kamagra en ligne

pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance: Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h – Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe pharmafst.com

Tadalafil 20 mg prix en pharmacie: Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance – cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

kamagra pas cher: kamagra 100mg prix – kamagra oral jelly

pharmacie en ligne france pas cher: Livraison rapide – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique pharmafst.com

kamagra livraison 24h: kamagra gel – Achetez vos kamagra medicaments

п»їpharmacie en ligne france: Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale pharmafst.com

Cialis en ligne: Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne – Cialis sans ordonnance 24h tadalmed.shop

indian pharmacy online shopping Online medicine order indian pharmacy online

best india pharmacy indian pharmacy Medicine From India

safe canadian pharmacies: Buy medicine from Canada – canadian drug prices

northern pharmacy canada: legit canadian pharmacy online – canadian pharmacy online store

mexican online pharmacy: RxExpressMexico – mexican online pharmacy

indian pharmacy online shopping Medicine From India MedicineFromIndia

вавада зеркало: вавада – vavada casino

вавада официальный сайт: вавада казино – вавада зеркало

pin-up: pinup az – pin up az

вавада официальный сайт: вавада – vavada casino

pin-up casino giris: pin up – pin up casino

вавада зеркало: vavada – вавада казино

вавада официальный сайт: вавада казино – вавада официальный сайт

пин ап казино официальный сайт: пин ап вход – pin up вход

pin-up casino giris: pinup az – pin-up

pin up: pinup az – pin-up casino giris

пин ап вход: пин ап казино официальный сайт – пинап казино

modafinil legality: buy modafinil online – buy modafinil online

https://zipgenericmd.com/# cheap Cialis online

Modafinil for sale: purchase Modafinil without prescription – modafinil 2025

https://modafinilmd.store/# modafinil 2025

https://maxviagramd.com/# discreet shipping

cheap Viagra online: generic sildenafil 100mg – same-day Viagra shipping

http://zipgenericmd.com/# online Cialis pharmacy

best price Cialis tablets: Cialis without prescription – Cialis without prescription

cialis 5 mg for sale: Tadal Access – cialis price comparison no prescription

buy cialis free shipping: cialis 5mg price comparison – cialis in las vegas

buying cialis internet: Tadal Access – does tadalafil work

tadalafil canada is it safe: combitic global caplet pvt ltd tadalafil – sildenafil and tadalafil

Licensed online pharmacy AU: Pharm Au 24 – Discount pharmacy Australia

buy antibiotics from canada buy antibiotics online uk cheapest antibiotics

Online drugstore Australia: Pharm Au 24 – Online drugstore Australia

Ero Pharm Fast: ed meds online – Ero Pharm Fast

https://pharmau24.com/# PharmAu24

buy antibiotics from india BiotPharm cheapest antibiotics

erectile dysfunction drugs online: Ero Pharm Fast – ed treatment online

buy ed medication online: Ero Pharm Fast – best ed pills online

Pharm Au 24: Pharm Au 24 – pharmacy online australia

https://biotpharm.shop/# buy antibiotics from india

Discount pharmacy Australia: PharmAu24 – Medications online Australia

Discount pharmacy Australia Discount pharmacy Australia pharmacy online australia

Ero Pharm Fast: Ero Pharm Fast – Ero Pharm Fast

https://biotpharm.com/# over the counter antibiotics

Pharm Au 24: PharmAu24 – Buy medicine online Australia

Over the counter antibiotics pills BiotPharm buy antibiotics from canada

Ero Pharm Fast: low cost ed medication – get ed meds online

pharmacy online australia Licensed online pharmacy AU Online medication store Australia

buy antibiotics from india: Over the counter antibiotics for infection – buy antibiotics over the counter

https://biotpharm.com/# get antibiotics quickly

It’s time to soar to new heights with BGaming! Launching the rocket to the stars means getting incredible winnings! Space XY is an exciting game with easy gameplay. Don’t hesitate to join a breathtaking ride to the stars and make a fortune. Predictor is a special tool that claims to guess the outcome of the upcoming round in this game. While it may seem appealing, relying on such solutions can be not the best idea. Aviator is based on the RNG, ensuring that each round is absolutely random and fair.Instead of using the 1Win Aviator predictor, focus on rules, mechanics, and algorithms. Besides, you can pick the best Spribe Aviator strategy to boost your chances in each round. PLAY RESPONSIBLY: jetxgame is an independent site with no connection to the websites we promote. Before you go to a casino or make a bet, you must ensure that you fulfil all ages and other legal criteria. jetxgame goal is to provide informative and entertaining material. It is offered only for the purpose of informative educational education. If you click on these links, you will be leaving this website.

https://www.horseracingnation.com/user/brudathnitib1971

For all new users, there is a limitation on the operation of the Aviator Predictor app. The app operates for 1 hour and is blocked for the following 23 hours. Users particularly value Parimatch’s transparent approach to bonuses, with fair wagering requirements that make it realistic to convert Aviator winnings from bonus funds into real cash. The project offers a comprehensive VIP program with special benefits for loyal Aviator fans, including personalized bonuses and faster withdrawal processing. If you don’t fancy scratch cards, we also offer keno games. Pick your lucky number – or a combination of fifteen numbers. And for every winning number you pick, you get paid real money. Every new user from Pakistan who wants to start playing Aviatrix 1win for real money can get a 500% welcome bonus up to PKR 226,750 by using a promo code during registration. After the deposit, this money will go into the bonus account balance and you can use it as you wish in your favorite game.

12:46 | Lima, set. 19. En cuanto a los carretes y líneas horizontales para formar combinaciones ganadoras, este juego no cuenta con estas funciones comunes. Su forma de pago, es mediante los multiplicadores que vayas obteniendo. Los consigues acertando los goles de manera consecutiva. Puedes anotar desde un gol, hasta la cantidad de cinco. Además, ten en mente que puedes realizar tu apuesta no solo desde tu laptop o PC, sino que también puedes jugar desde tu celular o tablet. Por lo tanto, creemos que no hay más excusas para no realizar tu primera o décima apuesta en Penalty Shootout. Penalty Shoot-Out: Street Apostar responsablemente es clave para una buena experiencia. Te recomendamos usar las herramientas de juego responsable en las casas que sugerimos para establecer límites y detectar hábitos no saludables. Asimismo, te invitamos a revisar nuestras reseñas antes de elegir el sitio de apuestas ideal para ti.

https://b.io/maisentseltkar1970

Con esta premisa resuelta, simplemennte abre la app de Google y en la barra de búsqueda teclea “Mundial Qatar 2022”, si bien también te va a salir con otras búsquedas relacionadas como “Mundial fútbol” o incluso “Mundal fumbol” porque bendito Google. Juego de fútbol en línea Fútbol Unblocked Game Se concederá un tiro penal siempre que un jugador cometa una infracción sancionable con libre directo dentro de su área penal o fuera del terreno de juego como parte del juego, según se estipula en las Reglas 12 y 13. La selección jugará la semifinal de la Nations contra Francia tras superar a una sólida Países Bajos en los penaltis después de un intercambio de golpes extenuante. 1. La pelota está todo el rato de izquierda a derecha hasta que se detiene. Solución: En la vista de diseño, hay que cambiar la velocidad de la pelota a 0 (por defecto pone 100)