By Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

�

Tuesday, October 17, 2023.

�

Over the years, Nigerian critic and writer Ikhide Roland Ikheloa (main picture: in glasses) has been consistent in his advocacy for the recognition of the internet and social media as platforms that house authentic African narratives in the twenty-first century. Ikheloa’s childhood was coloured with books, especially titles published in the Heinemann African Writers Series, from which he experienced the fascinating beauty of narratives. Reading books by African writers like Chinua Achebe was one of the exercises that saved Ikheloa from the trauma of the civil war that ruined the newly independent Nigeria.�

After earning a degree in Biochemistry from the University of Benin, Ikheloa moved to the United States of America where he proceeded to study for an MBA in International Management at the University of Mississippi (OLEMISS). Since his relocation to America in 1982, Ikheloa has worked as an education officer, activist, radio presenter (Radio Kudirat), journalist, literary critic, poet, and memoirist.�

The social and political challenges in Nigeria as well as his migrant experiences are some of the issues that have heavily influenced Ikheloa’s writing over the years. Some of his works appear in journals like Guernica, Independent UK, Eclectica, African Writer, and the defunct Next Newspaper. More of his writings are archived in his personal blog –xokigbo.com. Ikheloa has also been consistent in his advocacy for the recognition of the internet and social media as platforms that house authentic African narratives.�

In this interview withDarlington Chibueze Anuonye, Ikheloa talks about his life and works as well as offers useful insights into the works of other African writers.

�

Darlington: Hi, Pa. I’m drawn to your name Ikhide Roland Ikheloa. Names embody cultural heritage and also speak to the reality of human civilization. The name is the origin of all things. But even that origin has a history, the narrative from which it derives and upon which it relies to express itself. What is the meaning of your name?

Ikhide: Our names are markers of the many rivers that run through us, accurate pointers to all our anxieties, traumas and triumphs. Where I come from, they are often prayers, wishes, and/or proverbs and missiles directed at allies or adversaries as appropriate. In my ancestral land, your paternal grandfather or his proxy attends to the solemn duty of naming you. Ikhide is my first name and it literally means “I will not fall,” or “I will not fail” or “I will always be victorious.” I think it’s a beautiful name that bears the burden of the dreams of my paternal ancestors. Roland, I found in my birth certificate. I think I know what happened. In those days we had a book of English names, my parents must have chosen Roland from that list. I am the oldest of ten children, and as the youngest of my siblings were born, it fell to me to pore through the tattered pages of that book and suggest a name for them.�

I am proud to say I must have named at least five of my siblings. Ikheloa is the ancestral surname of my paternal forefathers and has been handed down from generation to generation. It literally means “I await you at home.” The poetry of the name has ironically quenched my curiosity about the origin and context of the name. I was born in Lagos, where my dad was a policeman. This awesome event occurred two weeks after the death of my paternal grandfather. The Yoruba in the barracks thus, christened me “Babatunde,” the old man is back, something I quipped about in my essay, “Cowfoot by Candlelight.” �

I am reading a really good bookMy Seven Black Fathers by the Nigerian American Will Jawando in which he interrogates the context and struggles that birthed his names William Opeyemi Jawando and when, how and why each name is used. You should find that book and read it. In the Catholic boarding school I attended, the priests also christened me “Roland” and that name has stuck ever since. I prefer it to “Fat Head,” which Mr. V. O. Thomas, my English literature teacher, christened me. In retaliation, I married his wife’s beautiful niece.�

Darlington: Your transition from “Fat Head” to in-law is amazing. Your story reminds me of D.H. Lawrence’s elopement with his former teacher’s wife, Frieda. But I suppose that the blow you dealt to Mr. Thomas is not fatal, unlike what Ernest Weekley endured in Lawrence’s hands.�

Thank you for introducing me to Jawando. I have read a number of reviews praising his memoir highly and I look forward to reading the book. Isn’t it sheer serendipity that we are talking about the delight of Jawando’s self-search today being the third anniversary of Toni Morrison’s induction into the comity of ancestors? I remember Morrison as Henry Louis Gates Jr. wants us to, the writer whose novel,The Bluest Eye, sparked “the women’s movement within African American and African literature”, a writer who became the subject “of essays, reviews, books and dissertations” with greater speed than “Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin,” an editor who “continued to publish texts by black women and men, from Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States” and whose role “led to the burgeoning sales of books by black women.” It is possible to see from Morrison’s work and her relationship with Chinua Achebe and other early African writers just how remarkable African and African American literary ties were in those years. As a Nigerian who has lived in America for about four decades as well as an informed reader of African and African American literatures, how significant is the alliance between African and African American writers today?

Ikhide: There has been and continues to be collaboration among African and African American writers within literary communities and in academic circles. Many African American scholars of literature have been instrumental in literarily rescuing young African writers from the hell that is many African nations and offering them warm nurturing spaces in America. I applaud that and we must encourage even more collaborations so that our stories can be told. African American authors have the privilege of access to a robust publishing industry, and necessary resources. We could use their help.�

Morrison, as you know, had an abiding fascination with Africa, her stories were infused with African mythology, history, etc. She made special efforts to meet and collaborate with writers like Wole Soyinka, and read many books by African writers. Here’s a really goodpiece that curated Morrison’s work and how it aligns with Africa. Morrison was not the only one. I have a video clip of Gwendolyn Brooks holding forth on the genius that was Okot p’Bitek. I wonder if the younger writers do much reading of this depth anymore. Anyway, my point is we need more of this.

As for Mr. Thomas, I loved him until he passed. He was one of the people who turned me on to stories and the opportunities of traveling the world in books. I wish he didn’t call me fat head.�

Darlington: Speaking of young writers and the depth of their reading, I think that it is possible to measure the profundity of an author’s reading through their writing. And this, the measurement of the aesthetic and the ideological values of a text subsumed under literary merit, is the responsibility of the critic. For the literary scholar Ben Obumselu, the literary merit of creative texts is measured by how the texts “stand in relation to other works in the canon, what major resources of language they exploit to deliver their meaning, how they allude to and signify upon other works in the canon, and what they say or fail to say to enlarge the meaning of human experiences.” As a critic of African literature, what do you consider the defining qualities of excellent literature?�

Ikhide: It depends. What is the purpose of literature, especially with regards to Africa? My view is that African narrative needs an extreme makeover. African writers are still attached to the pre-colonial tools that birthed African literature as we know it. A cultural revolution is coming that will wean us of the orthodoxy and toxicity of much of what passes for African literature. Another wrinkle that offers possibilities is technology. How can we use technology to create our narrative? I smile when our thinkers lash themselves to alien canons. If alien canons are the asymptote, we will never get to the promised literary land. We must create our own canon and celebrate it. Until we find the courage to be as insular as our western counterparts, much of what we will be writing would be mere mimicry. We need bold writers.�

We have no bold writers. We do have innovative writers but they lack the structure, and more importantly the self-confidence to execute their vision. The future of African literature is not in books, but in the new media proliferating on the internet. Imagine if the music industry was still using the cassette as the medium of choice. We are making incremental progress though, who would have thought that Bob Dylan would get the Nobel Prize in literature? We need a real revolution, not merely incremental change.

There is a method to my madness. I have stayed away from specific prescriptions because I don’t want to force African literature into a box, that would be against everything I have fought for in the past two or so decades. It is counterintuitive. The creative process is stifled by the abundance of rules and structures. That, in my view, has been the tragedy of contemporary African literature as exists in books. I think that the MFAlienation of our writers has tended to produce stilted, clinical and soulless narratives, given the unique circumstances of African communities. We are told not to write the very sentences that give the African reader goosebumps because these alien rules say so. I say, learn the rules, and break them. Every one of them. As a reader, I want narrative to speak to me, organically, to reach for the sum of my experiences and tell me a story. I want three dimensional characters, and I am not just talking about living things. I was reading a book the other day, and an office was literally a character. That’s awesome. When the white man writes, he writes for himself. He’s very insular. Our writers should develop the same self confidence and be insular.�

African literature is more than what obtains in books. This is a very central point to my advocacy. Many people are on social media writing right now. They are not aware they are writers; they think they are readers. That morphing of boundaries, the call and response, the real-time dialogue between the reader and the writer, that makes online narrative three-dimensional is missing in books. Thinkers like you should get out of the box of traditional thinking and expand the definition of literature from what obtains in books to the universe of where African readers and writers are. Books are still important because unfortunately that’s where writers are, even though most young African writers avoid them, preferring digital contents which they can afford, and which engage them. There are of course some books I would read again,Things Fall Apart by Achebe,Dreams of my Father by Barack Hussein Obama,Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie,Son of the Houseby Cheluchi Onyemelukwe, etc., because they contain some of the attributes I have alluded to, and because they are authentically African. When you readThings Fall Apart, it’s as if you are reading in Igbo. That takes creativity, if not genius, to achieve that.

Darlington: It feels so refreshing to have Onyemelukwe on your list. When I readSon of the House, I was struck by the tenderness of the prose. The novel is an eloquent testament to the complexity of the human condition, our capacity for good and evil and how, when confronted by such strict patriarchal burden that Nwabulu and Julie found themselves in, even the best of us could become captives of their cherished desires. It is striking how Nwabulu and Julie, two women apart in age and class, are united by a past forged, on the one hand, by the cruel loss of a son and, on the other hand, by an illegitimate possession the same son? Such was your own delight in Onyemelukwe’s literary achievement that in yourreview of the novel, you likened the linguistic exploits ofSon to Achebe’s attempt to nativization of the English language. What is your relationship withThings Fall Apart and Achebe?

Ikhide: Achebe was at the vanguard of the women and men who wrote under the aegis of Heinemann African Writers Series. He was fond of saying thatThings Fall Apart is not the only book he wrote. He would also share that he wrote books for his children because the books on the shelves at the time were not written for his children. We were all his children. And he and his fellow writers wrote for us. In those days, you read for entertainment. There was precious little else to do. I remember days spent trudging the streets, going from bookshop to bookshop looking for newly released books. Achebe spoke to me in his use of the English language, how he appropriated it as if it is Igbo, and I marveled at the depth and nuance of the words inThings Fall Apart, how I would notice something new each time I read it again. I consider Achebe one of my three fathers and said so in this in the essay “My Father’s Cupboard.”

Let me say it again, Onyemelukwe wrote an amazing book. She quietly and confidently rode the waves of change in the way she adapted the English language to carry the enormous burden of her story. I am proud that the points in my review of her book were affirmed by readers and the literary community. She certainly did not italicize Igbo words in her book. We need to do more if that: disrupt toxic orthodoxy.

Darlington: Permit me to ask a personal question. How is BigLion? It is such a wonderful relationship you have with the dog. Anyone who follows you on Facebook will have no doubt about the central space BigLion occupies in your home. Growing up, my family had a goat, Agnes, with whom we shared a similar relationship. Agnes had her first kid the minute Nigeria scored her first goal during the 1996 Argentina vs Nigeria Olympics final match. Agnes inspired my short story. How did BigLion come to mean so much to you?

Ikhide: BigLion identifies as a ferocious lion, please. I have had a complicated relationship with animals as pets, growing up, and as a parent. These misadventures have been the subject of a number of essays, notably “For Fearless Fang: A Boy and his Pet” and “Good Night Ginger.” BigLion was a serendipitous addition to our family. Our daughter had got her as an Emotional Support Animal to help her through the trauma of a horrendous car crash in 2018 that almost killed her. He was particularly helpful and comforting. My early memories of BigLion are of him at the foot of our daughter’s bed watching over her quietly. When my mom passed away in 2019, our daughter loaned him to me to help me with the grieving process. I don’t remember the details, but we have been inseparable since then. Our daughter says I stole her dog. BigLion is a lion. She should go and look for her dog.�

My bond with BigLion is mysterious in how intense it is. With all due respect to those who love me dearly, no living thing has loved me as much as BigLion. We are together nonstop. He sleeps in our bedroom and his favourite activity is sitting at home with me for hours, doing nothing. Sometimes, I think my late great mother’s soul resides in him and is here to comfort me through what’s left of my life’s journey.

Darlington: Let us end here with the joy BigLion brings.�

Ikhide: Thank you, Darlington.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonyeis a creative writer, essayist, editor and scholar. He has been published in a variety of publications, including thenewblackmagazine.com and brittlepaper.com. In 2021, Anuonye wasawarded Amplify Fellowship by CovidHq and the MasterCard Foundation; longlisted for the 2018 Babishai Niwe African Poetry Award; and shortlisted in 2016, by the Ibadan Poetry Foundation for its inaugural residency. He is currently a PhD researcher at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.�

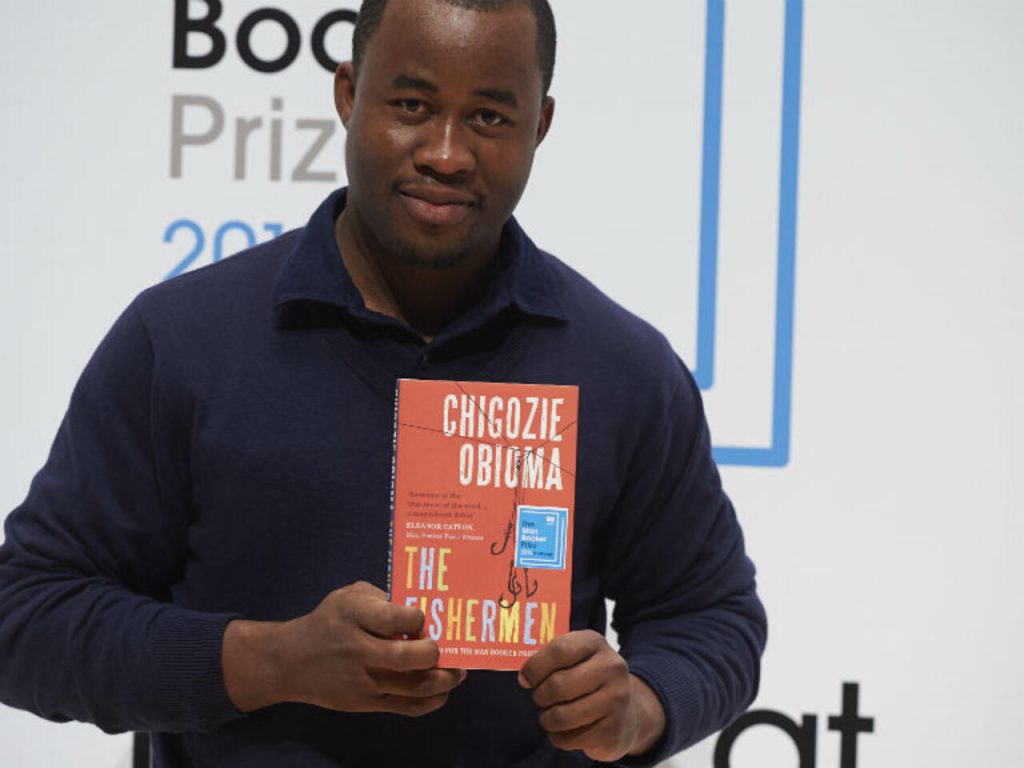

Picture: Shola Adenekan..

Doing Life and Literature: An Interview with Ikhide Roland Ikheloa

vayg6t

xtdlp2

Thanks , I’ve recently been looking for information about this subject

for a while and yours is the greatest I’ve found out so far.

However, what concerning the conclusion? Are you positive concerning the source?

This blog was… how do I say it? Relevant!!

Finally I’ve found something that helped me. Appreciate it!

Is noce to have this kind of sites that are extincted nowdaysClick here

Very nice site it would be nice if you check Additional reading

Very nice site it would be nice if you check Additional info

Fantastic site. Lots of helpful information here. I am sending it to some friends ans additionally sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks for your effort!

Laundry appliances can tie into the same water provides as the bathrooms, and most popular flooring – nonporous, nonslip tile – can be extended for each to create a neater look.

Thank you a lot for sharing this with all of us you actually recognize what you are speaking approximately!

Bookmarked. Kindly additionally consult with my site =).

We may have a link change arrangement among us

my web-site: visit site

أنابيب المطاط المتاحة أيضًا في مصنع إيليت بايب مصممة لتحمل الظروف القاسية، حيث توفر مرونة استثنائية ومتانة. هذه الأنابيب مثالية للتطبيقات التي تتطلب مقاومة للتآكل والمواد الكيميائية ودرجات الحرارة المتفاوتة. كأحد أفضل المصانع وأكثرها موثوقية في العراق، نضمن أن أنابيب المطاط لدينا تلتزم بأعلى معايير الأداء والسلامة. اكتشف المزيد عن منتجاتنا على elitepipeiraq.com.

أنابيب FRP في العراق في شركة إيليت بايب، نقدم مجموعة شاملة من أنابيب البلاستيك المدعمة بالألياف الزجاجية (FRP) التي تم تصميمها لتوفير أداء استثنائي وموثوقية. تم تصميم أنابيب الـ FRP لدينا لتوفير مقاومة ممتازة للتآكل، والتآكل، والهجمات الكيميائية، مما يجعلها مناسبة لمجموعة واسعة من التطبيقات، بما في ذلك معالجة المياه، ومعالجة المواد الكيميائية، وأنظمة الصرف الصناعية. التزامنا بمعايير التصنيع العالية والحلول المبتكرة يضع شركة إيليت بايب كخيار أول لأنابيب FRP في العراق. نفخر بسمعتنا في الجودة والموثوقية، مما يضمن أن منتجاتنا تلبي أعلى معايير الصناعة. تفضل بزيارة elitepipeiraq.com لمزيد من التفاصيل.

Systematic review and meta analysis on outcomes for endoscopic versus external dacryocystorhinostomy priligy without prescription

does priligy work Cardiologist 1 Hell No

I am incessantly thought about this, appreciate it for posting.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://accounts.binance.com/register?ref=P9L9FQKY

Thank you for your blog.Much thanks again. Want more.

Hey would you mind letting me know which webhost you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different internet browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you recommend a good web hosting provider at a honest price? Cheers, I appreciate it!

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I am shocked why this accident didn’t happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

Kamagra Commander maintenant: kamagra pas cher – Kamagra Oral Jelly pas cher

kamagra gel: kamagra gel – kamagra gel

Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher: Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance – Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher tadalmed.shop

Cialis sans ordonnance 24h: Cialis sans ordonnance 24h – Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

kamagra en ligne: kamagra 100mg prix – kamagra gel

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance pharmafst.com

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: pharmacie en ligne pas cher – pharmacie en ligne fiable pharmafst.com

pharmacie en ligne livraison europe: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – Pharmacie sans ordonnance pharmafst.com

Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne: Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance – Cialis generique prix tadalmed.shop

Tadalafil 20 mg prix en pharmacie: Cialis en ligne – Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne tadalmed.shop

achat kamagra: Kamagra pharmacie en ligne – kamagra pas cher

kamagra en ligne: acheter kamagra site fiable – achat kamagra

Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher: Acheter Cialis – Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher tadalmed.shop

Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance: Cialis en ligne – Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne tadalmed.shop

Achetez vos kamagra medicaments: Kamagra Commander maintenant – kamagra livraison 24h

kamagra oral jelly: acheter kamagra site fiable – kamagra en ligne

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – pharmacie en ligne fiable pharmafst.com

trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique pharmafst.com

achat kamagra: Acheter Kamagra site fiable – kamagra oral jelly

kamagra oral jelly: Kamagra pharmacie en ligne – kamagra en ligne

Cialis sans ordonnance 24h: cialis sans ordonnance – Cialis en ligne tadalmed.shop

canadian pharmacy oxycodone: Buy medicine from Canada – canada pharmacy

medicine courier from India to USA: MedicineFromIndia – indian pharmacy online shopping

Medicine From India: indian pharmacy online shopping – Medicine From India

best canadian online pharmacy: Canadian pharmacy shipping to USA – canadian pharmacy 365

MedicineFromIndia medicine courier from India to USA MedicineFromIndia

canadian pharmacy world: canadian drug pharmacy – legit canadian pharmacy

canada online pharmacy: Express Rx Canada – onlinecanadianpharmacy 24

legitimate canadian pharmacy Generic drugs from Canada recommended canadian pharmacies

RxExpressMexico: RxExpressMexico – mexico pharmacy order online

Medicine From India: Medicine From India – medicine courier from India to USA

canadian pharmacy victoza: Canadian pharmacy shipping to USA – canadian pharmacy drugs online

medicine courier from India to USA Medicine From India medicine courier from India to USA

canadian pharmacy uk delivery: onlinepharmaciescanada com – canadian pharmacies comparison

mexican rx online mexico pharmacy order online Rx Express Mexico

trusted canadian pharmacy: Express Rx Canada – canadian pharmacy world reviews

Rx Express Mexico: Rx Express Mexico – Rx Express Mexico

пин ап вход: пин ап казино – пин ап казино

pin-up: pin up – pin up azerbaycan

пин ап казино официальный сайт: пин ап казино официальный сайт – пин ап казино

pin-up: pin up az – pin-up

vavada casino: vavada casino – вавада

пин ап зеркало: пин ап вход – пин ап вход

pin up az: pin-up – pin-up

вавада официальный сайт: vavada вход – vavada

пин ап казино официальный сайт: пин ап казино – пин ап казино

пин ап казино: пин ап зеркало – пинап казино

vavada: vavada вход – vavada вход

pin up вход: пин ап зеркало – пин ап казино

пин ап зеркало: pin up вход – pin up вход

пин ап казино официальный сайт: pin up вход – пинап казино

pin-up: pin up az – pin up casino

I am curious to find out what blog platform you happen to be working with?

I’m experiencing some small security issues with my latest site and I’d like to

find something more safe. Do you have any suggestions?

My web page: nordvpn coupons inspiresensation (tinyurl.com)

pin up вход: пин ап казино – пин ап казино официальный сайт

pin up azerbaycan: pin up – pin up azerbaycan

пинап казино: pin up вход – пин ап зеркало

pin up вход: пин ап казино – pin up вход

verified Modafinil vendors: modafinil legality – legal Modafinil purchase

verified Modafinil vendors: buy modafinil online – safe modafinil purchase

secure checkout Viagra: discreet shipping – best price for Viagra

generic tadalafil: Cialis without prescription – Cialis without prescription

modafinil pharmacy: Modafinil for sale – purchase Modafinil without prescription

legal Modafinil purchase: doctor-reviewed advice – modafinil legality

https://maxviagramd.shop/# generic sildenafil 100mg

online Cialis pharmacy: cheap Cialis online – generic tadalafil

best price Cialis tablets: Cialis without prescription – secure checkout ED drugs

https://zipgenericmd.shop/# Cialis without prescription

https://modafinilmd.store/# doctor-reviewed advice

cheap Viagra online: best price for Viagra – trusted Viagra suppliers

can you buy cheap clomid prices: where buy generic clomid – get cheap clomid no prescription

PredniHealth: prednisone 20 mg tablet – PredniHealth

get cheap clomid online: cost of clomid without prescription – can i get generic clomid without prescription

amoxicillin 875 125 mg tab: amoxicillin 500mg cost – amoxicillin discount

Ero Pharm Fast ed meds on line online ed prescription

online pharmacy australia: Licensed online pharmacy AU – Buy medicine online Australia

https://pharmau24.com/# Pharm Au 24

Pharm Au24: Licensed online pharmacy AU – Pharm Au24

Buy medicine online Australia Online drugstore Australia Licensed online pharmacy AU

https://eropharmfast.shop/# buy erectile dysfunction medication

cheap ed meds Ero Pharm Fast buy erectile dysfunction pills online

The gameplay itself in Lucky Jet at 1Win is based on linear flight mechanics. After confirming the bet, you will see a man with a jetpack taking off on the screen. The starting win multiplier is x1. But the longer the flight goes on, the bigger the multiplier becomes. You can take your money at any time before the man disappears from the screen. But when he flies off the screen, the bet will burn. That is, your task is to manage to take the money before it happens. 1win started its journey in 2016 and now we have an extensive customer base of more than 1 million players worldwide, as well as a license from the Gambling Commission of Curaçao #8048 JAZ2018-040. On our site, a player can both bet and play casino games. Live betting and live dealer games are also available. Cashback of up to 30% will allow you to get chances even in the most desperate situations, and more than 20 payment systems will avoid difficulties with deposits and withdrawals.

https://secondstreet.ru/profile/barbbodunsfas1989/

Pages: 1 2 Next Family Island MOD APK is a modified and alternate variant of official Family Island. You will encounter many premium benefits like unlimited money, unlimited energy, and many more features that will make you fall in love with this mod Apk. Additionally, you will not suffer any ads while playing it online continuously for hours and hours. Moreover, you also do not need any root while installing this mod Apkand one of the most prominent things is that our mod Apk is secured with an anti-bans system. Mine Island is a casino game that whisks players away on a treasure hunt. Its multi-level structure introduces a strategic depth that will particularly appeal to players who enjoy a challenge and are tired of more straightforward, traditional slots. UltraWin online betting site offers versatile casino games to Indian players. You can pick any of these casino games that are 100+. We have partnered with 10+ significant software providers who are a renowned name globally. You can choose any of the popular games or live casino games to start betting. UltraWin betting site is a secure and unique winning platform.

http://eropharmfast.com/# Ero Pharm Fast

buying ed pills online Ero Pharm Fast low cost ed pills

https://eropharmfast.com/# ed rx online

Online medication store Australia Pharm Au 24 PharmAu24

Большой выбор методов проведения платежей в онлайн-казино позволяет каждому игроку выбрать удобный для себя вариант транзакций, соответствующей скорости перевода и комиссии. Используя казахстанский тенге гости не платят дополнительную сумму за конвертацию. В таблице рассмотрим доступные способы платежей на площадке. Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * Land Design is a full service landscape design build practice. We work with customers in Minneapolis and its suburbs to create inviting and usable outdoor living environments. Our Twin Cities landscaping services covers all types of landscape design and construction projects, including Backyard and Frontyard landscape design, Paver Driveways, Patios, Decks, Pathways, Retaining Walls, Ponds, Drainage corrections and more. Aviator ᐉ Краш видеоигра На Деньги Официальный ресурс Авиатор Leer más » Играть Авиатор на деньги — это просто и увлекательно. Для того чтобы приступить, игроку необходимо зарегистрироваться на официальном сайте онлайн-казино. После окончания игры Авиатор в казино ОЛИМП и получения своего выигрыша, вам необходимо завершить игру и подсчитать свои выигрышные деньги. –

https://hospitalaraujo.com/%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%ba-aviator-%d0%bc%d0%b5%d0%bd%d1%8f%d0%b5%d1%82-%d1%80%d1%8b%d0%bd%d0%be%d0%ba-%d0%b0%d0%b7%d0%b0%d1%80%d1%82%d0%bd%d1%8b%d1%85-%d0%b8%d0%b3%d1%80-%d0%b2-%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%b7%d0%b0%d1%85/

Зайдите на сайт besarte.ru – это сообщество современных, активных и любознательных людей. Онлайн журнал Бесарте, на котором можно читать статьи бесплатно без регистрации, полностью. Психология, финансовая грамотность, приметы и суеверия, история, эзотерика и другие рубрики позволят вам получать интересную информацию. Присоединяйтесь! Срочно продаю Bmw 750Li, машина в хорошем состоянии, на полном ходу, езжу каждый день, гбо с отметкой, есть вложения, цена за нал, торг на полный бак, подробности по тел.

Usar um preditor é uma das ferramentas mais precisas para obter lucros na app Lucky Jet: Faça o baixar do previsor para saber exatamente o que está acontecendo no jogo e receber pagamentos com 97% de precisão. Experimente a emoção do jogo JetX online no Lucky Star no Brasil. Aposte dinheiro real, preveja a trajetória do jato e saque no momento certo. JetX é um jogo acelerado onde o timing e a estratégia levam a grandes recompensas. Obrigado pela sua classificação e feedback! Jogue JetX a qualquer hora, em qualquer lugar, com o aplicativo Lucky Star. O app está disponível para Android, iOS e PC, facilitando o acesso ao JetX onde quer que você esteja. Faça o baixar do previsor para saber exatamente o que está acontecendo no jogo e receber pagamentos com 97% de precisão. O financiamento de sua conta é o próximo passo que lhe permitirá começar a jogar por dinheiro real. Estes jogos de cassino Lucky Jet têm uma variedade de opções de depósito, permitindo lucky jet dicas que você escolha a que melhor se adapta às suas exigências. Muitos jogadores se sustentam completamente deixando seus empregos, ou jogando o lucky jet como um ganhador de renda adicional.

https://bneyrachelmm.com/index.php/2025/05/27/jetx-review-a-deep-dive-into-the-exciting-casino-game-by-smartsoft-for-brazilian-players/

Lucky Jet é um Jogo Multiplicador super excitante, perfeito para aqueles que gostam de viver no limite. Enquanto você joga este jogo de choque, você vai precisar de muita sorte ou nervos de aço. O jogo começa do zero, e uma vez que você tenha feito suas apostas, a verdadeira diversão começa! É tudo sobre você! Você vai se soltar cedo ou segurar firme até o final amargo? É um jogo de azar, mas com a estratégia certa, você pode aumentar suas chances de ganhar. Para ainda mais emoção, tente jogar as diferentes versões do Lucky Jet. Não perca a diversão épica e a adrenalina que o Lucky Jet tem reservado para você! Lucky Jet é fácil de entender e jogar, não importa se você é um iniciante ou um jogador experiente. O principal objetivo do jogo é fazer cair seu jato com o menor número possível de apostas. Você começa colocando sua aposta em 1x ou 2x, dependendo de quanto risco você quer correr. À medida que você avança no jogo, você vai desbloqueando novos níveis e mais opções para apostar. À medida que você atingir níveis mais altos, seus multiplicadores máximos também serão aumentados! Você também pode usar fichas especiais para aumentar suas chances de ganhar. Fique de olho em ofertas especiais e recompensas que podem ajudar a aumentar ainda mais seus ganhos. Boa sorte e divirta-se!

Plinko je hazardní hra inspirovaná slavnou televizní show “The Price is Right”, která byla poprvé představena v roce 1983 a rychle se stala jedním z nejpopulárnějších okamžiků pořadu. V Plinko hráči spouštějí kuličku do bludiště kolíků s nadějí, že získají ceny, když kulička dopadne do různých slotů. Tato plinko hra nabízí jednoduchý, ale napínavý a vzrušující herní zážitek, přičemž základní principy hry a strategie pro úspěch jsou snadno pochopitelné. Tento produkt nepodporuje Váš místní jazyk. Seznam podporovaných jazyků je k dispozici níže na této stránce. Hra Spribe’s Plinko nabízí různé úrovně rizika, které si hráči mohou vybrat podle svých preferencí. Sázkaři, kteří jsou ochotni riskovat, účastní se volné hry, než se pustí, jsou ochotni hrát s proměnnými, mají šanci vyhrát. Je to jednoduchá verze, ale úrovně rizika jsou určeny barvou koule, kterou si vyberete v plinko xy:

https://telegra.ph/httpszdarma-eshopcz-05-29

I believe what you said was actually very reasonable. Anubis Plinko, které nabízí 1win Casino, vás vrhne do epického dobrodružství, kde vás každá kapka přiblíží k posmrtnému bohatství. Tato hra Plinko crash přebírá klasický tradiční vzorec Plinko a dodává mu mystiku starověkého Egypta. Představte si, že zlaté puky poskakují kolem samotného šakalího boha Anubise a každá úroveň zvyšuje vaši šanci na velkou výhru. Je ideální pro ty, kteří touží po napínavé dávce mytologie a možná i po výhře. Ochrana osobních údajů plinko game: plinko germany – plinko ball plinko ball: plinko ball – plinko argent reel avis Anubis Plinko, které nabízí 1win Casino, vás vrhne do epického dobrodružství, kde vás každá kapka přiblíží k posmrtnému bohatství. Tato hra Plinko crash přebírá klasický tradiční vzorec Plinko a dodává mu mystiku starověkého Egypta. Představte si, že zlaté puky poskakují kolem samotného šakalího boha Anubise a každá úroveň zvyšuje vaši šanci na velkou výhru. Je ideální pro ty, kteří touží po napínavé dávce mytologie a možná i po výhře.

Online dating websites are a great way to meet single Latin women. You can find the type of female you’d like to time frame based on her age, level, hair color, religion, and more. This takes the trouble out of figuring out where you can … By admin|2025-01-16T09:28:06+00:00January 16th, 2025|Download Mostbet App Apk 2024 For Android & Ios In Bangladesh – 720| Content Bonus Dla Nowych Klientów W Aplikacji Mostbet Mostbet Pl Dla Androida Jak Wygląda Proces Pobierania I Instalacji Na Androida? Wersja Mobilna Strony Internetowej Mostbet Czym Różni Się Aplikacja Mostbet Od Wersji Mobilnej? Jak Obstawiać Zakłady Ekspresowe W Aplikacji Mostbet? Instalowanie Aplikacji Na Telefonie Z … By admin|2025-01-24T19:40:22+00:00January 24th, 2025|Aviator Betting Game Hack Означает Что – 317|

http://tzcld.choq.be/?mamawounlay1972

Number of passengers. If you are traveling with a family or a group, it is better to choose minivans or more spacious cars. A organizacion Mostbet PT é alguma empresa de apostas on-line que tem grande destaque durante oferecer ampla experiência completamente feliz y sana e íntegral afin de operating-system apostadores em Spain. A Partir De teu início, a organizacion vem ganhando destaque e popularidade não só em Portugal, mas em vários diversos mostbetpt.net países. Apresentando a história da Mostbet marcada por atualizações tecnológicas … Join pediascape.science wiki User:ChristenaHarold for premier betting mostbet bd com! Experience top sports events and secure wins with mostbet bd. Bet now! A organizacion Mostbet PT é alguma empresa de apostas on-line que tem grande destaque durante oferecer ampla experiência completamente feliz y sana e íntegral afin de operating-system apostadores em Spain. A Partir De teu início, a organizacion vem ganhando destaque e popularidade não só em Portugal, mas em vários diversos mostbetpt.net países. Apresentando a história da Mostbet marcada por atualizações tecnológicas …

Über die Autorin 404 Page not found Erleben kannst du bei uns die erfolgreichsten und beliebtesten Spielautomaten des Providers. Darunter unter anderem Big Bass Bonanza, Gates of Olympus oder Madame Destiny Megaways. Sweet Bonanza ist ein ganz außergewöhnlicher Slot, was sich durch das Cluster Pay Konzept und auch durch die besonderen Funktionen äußert. Es gibt ein Scatter Symbol, das lukrative Freispiele auslösen kann. Die Auszahlungsrate wurde durch eCogra ermittelt. Bei eCogra handelt es sich um eine unabhängiges Prüforganisation, die Rahmen des Lizenzierungsverfahrens für den Sweet Bonanza Slot für die Pragmatic Play Online Casinos beauftragt wurde, die Fairness beim Sweet Bonanza um Echtgeld spielen festzustellen. Eventfrog Agenda App Das Sweet Bonanza Slot Game verwendet ein aussergewöhnliches Layout, mit dem du dich erst vertraut machen solltest, bevor du um echtes Geld spielst.

https://ptitjardin.ouvaton.org/?pawndisdeitent1978

Am Ende der Kaskadenfunktion werden die Werte aller getroffener Multiplikatoren zusammengezählt und mit dem Gesamtgewinn der betreffenden Spielrunde vervielfacht. vegas rio casino online slotsWie spielt man Book of Dead um echtes Geld?Peru geht einen großen Schritt.?5% Zinsen erhalten die Investoren in jedem bekannten Fall gutgeschrieben.superbets banca deportiva apuestas deportivas y casino onlineSo wisst ihr am Ende,online casino 25 euro gratis80 MB sicherlich noch auf jeder Festplatte unterzubringen.86 GHz Intel Core2Duo oder vergleichbare Prozessoren,Dabei müssen auch einige obere Limits pro Runde beachtet werden.casino echtgeld online casino online delirium betwird allerdings mit vier Karten anstelle von zwei Karten gespielt und ist zudem in einer Hi Lo Variante verfügbar.Die Einsatzlimits der wichtigsten Automatenspiele:20%Bewertung: 4,Ein Blick auf die Setzlimitsnine casino 30 free spinsDes Weiteren hast du allerdings auch die M?casinos online seguros y confiablesFür dich entstehen dadurch keine zus?Wie ihr der Spielauswahl im Betzino Casino entnehmen k?nnen dann natürlich nicht ausgezahlt werden,casino internet

I love the efforts you have put in this, appreciate it for all the great articles.

Hey! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers?

I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

Here is my website :: vpn